Okklusion und Haltung

Okklusion und Haltung

Zusammenfassung

In diesem Abschnitt von Masticationpedia werden wir uns mit einem viel diskutierten Thema auf dem Gebiet der prothetischen Rehabilitation und der Diagnose von Orofazialstörungen, einschließlich Kiefergelenksdysfunktionen, befassen. Wie wir sehen werden, gibt es eine Linie zwischen Befürwortern der Korrelation zwischen Haltung und dem Trigeminussystem und denen, die die Korrelation ablehnen. Um diese Korrelation zu bestätigen oder zu leugnen, würde es ausreichen, die Aufmerksamkeit auf die VEMPs (myogene vestibulär evozierte Potenziale) zu richten, um das neuronale Synergismus zu verstehen. Es wäre jedoch notwendig, gleichermaßen auf die synaptischen Modulationen zu achten, die bei diesem Phänomen auftreten, um zu verstehen, wie viel wir immer noch über die oben genannte trigeminale/vestibuläre Korrelation wissen. Denken Sie nur an den Rolleneffekt und bewerten Sie die durch Klick ausgelösten zervikalen vestibulären myogenen Potenziale (VEMPs) während der visuellen Rollbewegung, die eine illusorische Empfindung der Selbstbewegung (d. h. Vektion) hervorrief. Während der Vektion gibt es eine Zunahme der cVEMP-Amplitude, die positiv mit subjektiven Berichten über die Stärke der Vektion korreliert ist. Die experimentelle Schlussfolgerung ist daher, dass die einfache subjektive Empfindung der Abschnittsfähigkeit in der Lage ist, die Antwort der VEMPs zu modulieren, und dass dieses höhere kortikale Phänomen sich auch auf kurzzeitige vestibulospinale Reaktionen auswirken kann. Unabhängig davon, wer im Laufe der Zeit Recht haben wird, muss man immer sehr vorsichtig sein bei der Bewertung der von Patienten berichteten Symptome und klinischen Anzeichen und sich nicht von mehr oder weniger modischen Axiomen beeinflussen lassen, die sogar schwerwiegende Fehler in der Differentialdiagnose verursachen können, wie im klinischen Fall, den wir unten vorstellen werden.

Einführung

Als Einführung in den Abschnitt der Kapitel über "Okklusion und Haltung" können wir teilweise eine prägnante Einführung von Monika Nowak et al.[1] anführen, auf die wir die ersten konzeptuellen Reflexionen unseres nachdenklichen Linus anführen werden.

"Haltung wird als die Position des menschlichen Körpers und seine Orientierung im Raum verstanden, die die Analyse und Integration von Reizen aus drei Systemen erfordert: Sehen, vestibulär und Propriozeption. [2][3] Im Laufe der Jahre wurden zahlreiche Beobachtungen zu den Faktoren gemacht, die die posturale Stabilität beeinflussen. [4][5][6][7][8] Die Rolle des kraniomandibulären Systems wird nun zunehmend im Zusammenhang damit analysiert. [9][10][11][12] Viele Theorien versuchen, die Verbindung zwischen dem Kauorgan und der Haltung zu erklären, darunter myofasziale Ketten, Aktivierung oder Deaktivierung des Trigeminusnervs und die anschließende Interaktion im Hirnstamm. [13][14][15] Dies ist jedoch ein umstrittenes Thema in der wissenschaftlichen Gemeinschaft. Es gibt sowohl Beweise, die diese Beziehung unterstützen, als auch solche, [16][17][18][19][20][21] die sie ablehnen. [22][23][24][25]

Inhalt, der die Korrelation unterstützt

ChatGPT

Die Autoren der wissenschaftlichen Berichte, die die Zusammenhänge zwischen den betreffenden Systemen erkennen, geben zwei Hinweise auf mögliche Wechselwirkungen. Der erste, also aufsteigende Störungen, bezieht sich auf die Situation, in der eine schlechte Haltung und Störungen der peripheren Strukturen (z. B. der unteren Extremitäten) durch myofasziale neuromotorische Aktivitäten und die Dura mater die kraniomandibulären Strukturen funktional beeinflussen. Umgekehrt liegt eine Kette von absteigenden Störungen vor, wenn Anomalien der kraniomandibulären Region die Haltung und Körperbereiche, die weiter distal liegen, einschließlich des Beckens und der unteren Extremitäten, beeinträchtigen.[13][26][27][28]

Und dazu gibt es nichts zu sagen, denn niemand kann eine anatomisch-funktionelle Korrelation zwischen den vestibulären Systemen, dem Kleinhirn, dem Trigeminus und dem peripheren neuromotorischen System leugnen. Dies ist keine Meinung, sondern eine nachgewiesene wissenschaftliche Beobachtung, die bereits an anderer Stelle in Masticationpedia berichtet wurde.

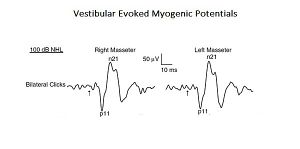

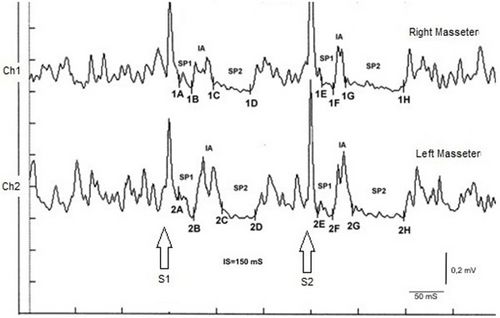

Figure 1: Vestibula Evoked Myogenic Potentials (see chapter 'Complex Systems' VEMPs, translated into Myogenic Vestibular Evoked Potentials are proof of this. Acoustic stimuli can evoke EMG reflex responses in the masseter muscle called Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials (VEMPs). Although these findings have previously been attributed to activation of cochlear (high-intensity sound) receptors, these may also activate vestibular receptors. Because anatomical and physiological studies in both animals and humans have demonstrated that the masseter muscles are a target for vestibular inputs, the authors of this study reevaluated the vestibular contribution for masseter reflexes. This is a typical example of a basic level 'Complex System' as it consists of only two cranial nervous systems but, at the same time, they interact by activating monosynaptic and polysynaptic circuits (Figure 1).

Tmj disorders and posture

It has been shown that changes in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) can have a direct impact on muscle activity in terms of posture, stability and physical performance.[17][29][30] However, there is a lack of high-quality studies using advanced measurement tools to better understand the phenomenon under investigation.[31] The study authors evaluated the impact of masticatory abnormalities on postural control and focuses on evaluating individuals with specific malocclusions that determine the anteroposterior position of the mandible. According to some researchers, malocclusion, like TMD, can affect the osteoarticular system of the whole body and become a source of persistent pain and favor the development and to become chronic of some postural defects. According to the cited authors, occlusal disturbances can lead to an altered stimulation of the periodontal proprioceptors, causing changes in the tension of the neck muscles and postural muscles and changes in the position of the head, followed by compensatory changes in the anatomical regions in their immediate vicinity. Over time, this can affect the posture, center of gravity position, or foot contact with the ground.[13][26][27][32][33]

This could also be true but at the same time it should be demonstrable in order not to make diagnostic errors such as the one we will present in the section dedicated to 'Occlusion and Posture. Indeed, the patient we will present exclusively reported a masticatory disorder such as to require continuous rehabilitative reconstructions from his dentist. How can we demonstrate this occlusal disturbance at the neuromotor level such that it can also condition the vestibular system, the cerebellum and other brain centres?

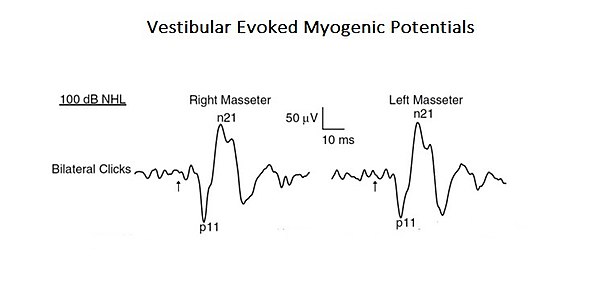

Figure 2:Trigeminal electrophysiological responses.

Faced with a marked asymmetry such as the one shown in Figure 2, we certainly cannot deny a trigeminal disorder which is often related to a malocclusion. In Figure 2A we can see a slight asymmetry of the interferential EMG trace between the right and left masseter as well as the MEPs of the trigeminal root (Figure 2B) as well as the absence of the action potential on the right masseter in the mandibular reflex responses (Figure 2C ). As we will see in the chapters concerning this patient, these abnormal trigeminal electrophysiological responses have nothing to do with occlusal disturbances, much less postural disturbances.

However, there is still a gap in scientific knowledge on the relationship between craniofacial structure and spinal postural control in patients with malocclusion. Furthermore, the available documents show problems related to the small number of subjects, the small number of tested parameters or the selection of reliable measurement tools.[23][34][35]

Malocclusion, which these studies focus on, can result from abnormalities in the structure and alignment of the bones of the jaw and mandible in relation to each other or from an abnormal arrangement of the dental arches.

Bruxism and Posture

Angle suggested a classification of occlusion and malocclusion based on the anteroposterior position of the first molar and the position of the canines.[36][37]Malocclusion is often a congenital condition, resulting from hereditary or environmental factors. It is also caused by local factors, such as an abnormal pattern of breathing or postural defects, as well as oral parafunctions such as nail biting or teeth grinding (bruxism).[37]According to Lombardo's analyses, occlusal anomalies occur on average in 56% of the general population.[38] Their prevalence increases with age. Given their increasing prevalence in later age groups and the consequences they entail, it is reasonable to expect a large number of adult patients who will require complex and expensive multidisciplinary treatment.[38][39]

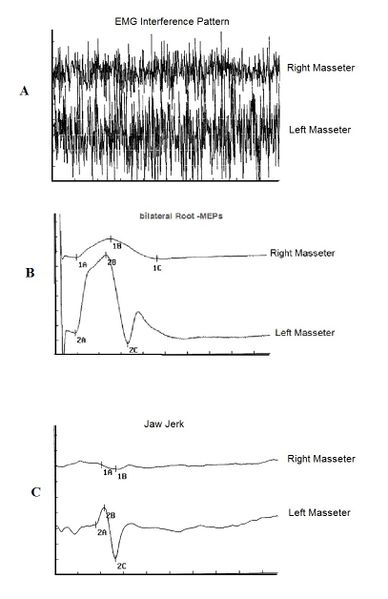

Regarding bruxism[37] we certainly cannot speak of scientific certainties or take into consideration the incidence of bruxism in the population because, as described in the specific chapter concerning our patient 'Bruxer', he had a perfect occlusion and neuromuscular responses apparently up to standard if it hadn't been for the study of the case and have highlighted a neuronal hyperexcitability with the test of the rcMIR masseter inhibitory recovery cycle (Figure 3).

Figura 3: rcMIR in brusiste patient Although the patient was in a state of neuronal hyperexcitability which affected the entire left leg with stiffness of the upper limbs, he never accused postural problems. With this we want to underline that although there are correlations between different cerebral association areas such as the vestibular, the trigeminal, the midbrain and so on, this does not give the clinician the right to base the diagnosis on these certainties. As, of course, we will repeat repeatedly throughout the 'Normal Science' section to justify the next section which will focus on the aspect of the anomalies and therefore the crisis of the paradigm.

Given the high proportion of patients with malocclusions [20][21] and the conflicting reports of these reports, [16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] the need for further knowledge and analysis of individual malocclusions and associated musculoskeletal abnormalities under dynamic and static conditions is reasonable. There is still a lack of research on the effect of occlusion on postural stability and plantar pressure distribution during standing and walking in the same group of adults with Angle Class I, II, and III.

Contents to refute the correlation

As far as the authors contesting the correlation between occlusion and posture are concerned, we can report the results of Giuseppe Perinetti et al.[23] of 122 subjects, including 86 males and 36 females (age range 10.8 to 16.3 years) who tested negative for temporomandibular disorders or other conditions affecting the stomatognathic systems, with the exception of malocclusion. An assessment of dental occlusion included dentition stage, molar class, overjet, overbite, anterior and posterior crossbite, scissor bite, mandibular crowding, and dental midline deviation. Furthermore, body posture was recorded through static posturography using a vertical force platform. Recordings were performed under two conditions:

- mandibular rest position (RP)

- dental intercuspid position (ICP).

The conclusion was that all posturographic parameters showed great variability and were very similar between recording conditions. Furthermore, a limited number of weakly significant correlations, mainly for the overbite phase, were observed when using multivariate models.

The author's current findings were that regarding the use of posturography as a diagnostic aid for subjects affected by dental malocclusion, they do not support the existence of clinically relevant correlations between malocclusion typology and body posture.

Another interesting article in the group contesting the correlation comes from Benjamin Scharnweber et al.[24] examined 87 male subjects with a mean age of 25.23 ± 3.5 years (18 to 35 years). The dental models of the subjects were analyzed. Postural control and plantar pressure distribution were recorded from a weight bearing platform. Possible orthodontic and orthopedic influencing factors were determined from a medical history or questionnaire. All tests performed were randomized and repeated three times each for intercuspid position (ICP) and locked occlusion (BO).

In this study, the ICP occlusal position was found to increase body sway in the frontal (p ≤ 0.01) and sagittal (p ≤ 0.03) planes compared to the BO position, whereas all other 29 correlations were independent of position of the occlusion.

For both ICP or BO cases, angle therapy, midline shift, crossbite, or orthodontic therapy was found to have no influence on postural control or plantar pressure distribution (p > 0.05).

In conclusion, the author confirms that persistent dental parameters have no effect on postural sway. Furthermore, postural control and plantar pressure distribution were found to be independent postural criteria.

- ↑ Monika Nowak,,Joanna Golec, Aneta Wieczorek, and Piotr Golec. Is There a Correlation between Dental Occlusion, Postural Stability and Selected Gait Parameters in Adults? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan; 20(2): 1652. Published online 2023 Jan 16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021652. PMCID: PMC9862361. PMID: 36674407

- ↑ Guez G. The Posture. In: Kandel E., Schwartz J., editors. Principles of Neural Science. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1991. pp. 612–623.

- ↑ Czaprowski D., Stoliński L., Tyrakowski M., Kozinoga M., Kotwicki T. Non-structural misalignments of body posture in the sagittal plane. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018;13:6. doi: 10.1186/s13013-018-0151-5.

- ↑ Iwanenko J., Gurfinkel V. Human postural control. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:17.

- ↑ Guerraz M., Bronstein A.M. Ocular versus extraocular control of posture and equilibrium. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2008;38:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.007.

- ↑ Hamaoui A., Frianta Y., Le Bozec S. Does increased muscular tension along the torso impair postural equilibrium in a standing posture? Gait Posture. 2011;34:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.06.017.

- ↑ Kolar P., Sulc J., Kyncl M., Sanda J., Neuwirth J., Bokarius A.V., Kriz J., Kobesova A. Stabilizing function of the diaphragm: Dynamic MRI and synchronized spirometric assessment. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;109:1064–1071. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01216.2009.

- ↑ Szczygieł E., Fudacz N., Golec J., Golec E. The impact of the position of the head on the functioning of the human body: A systematic review. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 2020;33:559–568. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01585.

- ↑ Tardieu C., Dumitrescu M., Giraudeau A., Blanc J.L., Cheynet F., Borel L. Dental occlusion and postural control in adults. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;450:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.005.

- ↑ Munhoz W.C., Hsing W.T. Interrelations between orthostatic postural deviations and subjects’ age, sex, malocclusion, and specific signs and symptoms of functional pathologies of the temporomandibular system: A preliminary correlation and regression study. Cranio. 2014;32:175–186. doi: 10.1179/0886963414Z.00000000031.

- ↑ Pérez-Belloso A.J., Coheña-Jiménez M., Cabrera-Domínguez M.E., Galan-González A.F., Domínguez-Reyes A., Pabón-Carrasco M. Influence of dental malocclusion on body posture and foot posture in children: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare. 2020;8:485. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040485.

- ↑ Amaricai E., Onofrei R.R., Suciu O., Marcauteanu C., Stoica E.T., Negruțiu M.L., David V.L., Sinescu C. Do different dental conditions influence the static plantar pressure and stabilometry in young adults? PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0228816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228816.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Cabrera-Domínguez M.E., Domínguez-Reyes A., Pabón-Carrasco M., Pérez-Belloso A.J., Coheña-Jiménez M., Galán-González A.F. Dental malocclusion and its relation to the podal system. Front. Pediatr. 2021;9:654229. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.654229.

- ↑ Myers T. Anatomy Trains: Myofasziale Leitbahnen (für Manual- und Bewegungstherapeuten) Elsevier Health Sciences; Berlin, Germany: 2015.

- ↑ Pinganaud G., Bourcier F., Buisseret-Delmas C., Buisseret P. Primary trigeminal afferents to the vestibular nuclei in the rat: Existence of a collateral projection to the vestibulo-cerebellum. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;264:133–136. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00179-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bracco P., Deregibus A., Piscetta R. Effects of different jaw relations on postural stability in human subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;356:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.055.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Manfredini D., Castroflorio T., Perinetti G., Guarda-Nardini L. Dental occlusion, body posture and temporomandibular disorders: Where we are now and where we are heading for. J. Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02291.x.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sakaguchi K., Mehta N.R., Abdallah E.F., Forgione A.G., Hirayama H., Kawasaki T., Yokoyama A. Examination of the relationship between mandibular position and body posture. Cranio. 2007;25:237–249. doi: 10.1179/crn.2007.037.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cuccia A., Caradonna C. The relationship between the stomatognathic system and body posture. Clinics. 2009;64:61–63. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000100011.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Marchena-Rodríguez A., Moreno-Morales N., Ramírez-Parga E., Labajo-Manzanares M.T., Luque-Suárez A., Gijon-Nogueron G. Relationship between foot posture and dental malocclusions in children aged 6 to 9 years. A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2018;97:e0701. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010701

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Iacob S.M., Chisnoiu A.M., Buduru S.D., Berar A., Fluerasu M.I., Iacob I., Objelean A., Studnicska W., Viman L.M. Plantar pressure variations induced by experimental malocclusion—A pilot case series study. Healthcare. 2021;9:599. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050599.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Michelotti A., Buonocore G., Farella M., Pellegrino G., Piergentili C., Altobelli S., Martina R. Postural stability and unilateral posterior crossbite: Is there a relationship? Neurosci. Lett. 2006;392:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.008.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Perinetti G., Contardo L., Silvestrini-Biavati A., Perdoni L., Castaldo A. Dental malocclusion and body posture in young subjects: A multiple regression study. Clinics. 2010;65:689–695. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010000700007.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Scharnweber B., Adjami F., Schuster G., Kopp S., Natrup J., Erbe C., Ohlendorf D. Influence of dental occlusion on postural control and plantar pressure distribution. Cranio. 2017;35:358–366. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2016.1244971.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Isaia B., Ravarotto M., Finotti P., Nogara M., Piran G., Gamberini J., Biz C., Masiero S., Frizziero A. Analysis of dental malocclusion and neuromotor control in young healthy subjects through new evaluation tools. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2019;4:5. doi: 10.3390/jfmk4010005.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Michalakis K.X., Kamalakidis S.N., Pissiotis A.L., Hirayama H. The Effect of clenching and occlusal instability on body weight distribution, assessed by a postural platform. BioMed Res. Int. 2019;2019:7342541. doi: 10.1155/2019/7342541.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Julià-Sánchez S., Álvarez-Herms J., Cirer-Sastre R., Corbi F., Burtscher M. The influence of dental occlusion on dynamic balance and muscular tone. Front. Physiol. 2020;10:1626. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01626.

- ↑ Pacella E., Dari M., Giovannoni D., Mezio M., Caterini L., Costantini A. The relationship between occlusion and posture: A systematic review. Orthodontics. 2017;8:WMC005374.

- ↑ Moon H.J., Lee Y.K. The relationship between dental occlusion/temporomandibular joint status and general body health: Part 1. Dental occlusion and TMJ status exert an influence on general body health. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011;17:995–1000. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0739.

- ↑ Souza J.A., Pasinato F., Correa E.A., da Silva A.M. Global body posture and plantar pressure distribution in individuals with and without temporomandibular disorder: A preliminary study. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2014;37:407–414.

- ↑ Ferrillo M., Marotta N., Giudice A., Calafiore D., Curci C., Fortunato L., Ammendolia A., de Sire A. Effects of occlusal splints on spinal posture in patients with temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. Healthcare. 2022;10:739. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10040739.

- ↑ Saccucci M., Tettamanti L., Mummolo S., Polimeni A., Festa F., Tecco S. Scoliosis and dental occlusion: A review of the literature. Scoliosis. 2011;6:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-6-15.

- ↑ Sforza C., Tartaglia G.M., Solimene U., Morgan V., Kaspranskiy R.R., Ferrario V.F. Occlusion, sternocleidomastoid muscle activity, and body sway: A pilot study in male astronauts. Cranio. 2006;24:43–49. doi: 10.1179/crn.2006.008

- ↑ Michelotti A., Buonocore G., Manzo P., Pellegrino G., Farella M. Dental occlusion and posture: An overview. Prog. Orthod. 2011;12:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pio.2010.09.010.

- ↑ Ishizawa T., Xu H., Onodera K., Ooya K. Weight distributions on soles of feet in the primary and early permanent dentition with normal occlusion. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2005;30:165–168. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.30.2.8x4727137678061m.

- ↑ Bernabé E., Sheiham A., de Oliveira C.M. Condition-specific impacts on quality of life attributed to malocclusion by adolescents with normal occlusion and Class I, II and III malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:977–982. doi: 10.2319/091707-444.1

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Okeson J.P. Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion.Mosby; Maryland Heights, MO, USA: 2019.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Lombardo G., Vena F., Negr P., Pagano S., Barilotti C., Paglia L., Colombo S., Orso M., Cianetti S. Worldwide prevalence of malocclusion in the different stages of dentition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020;21:115–122.

- ↑ Kawala B., Szumielewicz M., Kozanecka A. Are orthodontists still needed? Epidemiology of malocclusion among polish children and teenagers in last 15 years. Dent. Med. Probl. 2009;46:273–278