Encrypted code: Hyperexcitability of the trigeminal system

Encrypted code: Hyperexcitability of the trigeminal system

Abstract:This section introduces the Cognitive Neural Network (CNN) as an analytical tool for complex clinical diagnoses, particularly in the context of the patient known as "Bruxer," who suffers from severe nocturnal and diurnal bruxism. Building on the method described in the "Encrypted Code: Ephaptic Transmission" chapter, the CNN is used here to refine and decrypt the machine language of the Central Nervous System (CNS) and provide a clearer diagnostic framework. The case study emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between dental and neurological contexts, with a focus on trigeminal system excitability and hyperexcitability.

The diagnostic process begins by assessing the patient's clinical data, including a jaw jerk test that reveals slight asymmetry in amplitude, and progresses to using the CNN to evaluate specific PubMed results related to bruxism and the trigeminal system. The analysis highlights the relevance of electrophysiological tests, such as the recovery cycle of the masseter inhibitory reflex (rcMIR), in identifying hyperexcitability in the trigeminal motor system.

Following the rcMIR analysis, a brain MRI confirms the presence of a pineal cavernoma, providing a definitive diagnosis. The chapter concludes that bruxism is not solely a dental issue but involves CNS hyperexcitability, suggesting that it may be a form of orofacial dystonia. The final considerations propose that bruxism, when accompanied by orofacial pain (OP), should be viewed as a potential manifestation of central nervous system dysfunction, with implications for broader neurophysiological assessments and treatment.

Introduction

We have therefore reached the section of the Cognitive Neural Network' abbreviated to 'RNC' presented for the diagnosis of the case of our 'Mary Poppins' in the chapter 'Encrypted code: Ephaptic transmission' and which we will propose again as a diagnostic model to accustom the reader to the procedure , simple, intuitive but essential in clinical cases of complex diagnosis such as our patient 'Bruxer'. Our starting point, therefore, is the point of arrival of the phase preceding the 'RNC', ie the discriminatory phase of the contexts ( Coherence Demarcator). The low diagnostic weight derived from the neurological assertions , in fact, refers only to a modest difference in the amplitude of the jaw jerk. Also in this case the Cognitive Neural Network (CNN) can help us to focus the machine language code and decrypt it. We therefore follow the same procedure already described extensively in the chapter 'Encrypted code: Ephaptic transmission' and we will have the following result:

Bruxism (4398), trigeminal system (29), abnormality ( 5), excitability ( 3)The excitability of the trigeminal motor system in sleep bruxism: a transcranial magnetic stimulation and brainstem reflex study

Diagnostic sequences

1st Step: CNN Sequence

- Coherence Demarcator: As we have previously described, the first step is an initialization command of the network analysis which derives, in fact, from a previous cognitive elaboration of the assertions in the dental context and the neurological one to which the ' Coherence Demarcator' has given an absolute weight effectively eliminating the dental context from the process. From what emerges from the neurological statements the 'State' of the Trigeminal Nervous System appears relatively asymmetrical in amplitude for the jaw jerk, given an average of . This does not allow the initial purely neurological command to be entered in the Pubmed database as was performed for the previous clinical case of Mary Poppins. The initialization command will therefore be 'Bruxism' which will concern both data samples (dental and neurological).

- 1st loop open: This 'Initialization command', therefore, is considered as initial input for the Pubmed database which responds with 4398 clinical and experimental data available to the clinician. The opening of the first real cognitive analysis is elaborated precisely on the analysis of the first result of the 'CNN' corresponding to 'Bruxism'. In this phase, given the negativity of the dental report and the minimal positivity of the neurological context, it would be necessary to identify a neurological component for which 'Trigeminale system' is added as the 1st open loop.

- 2st loop open: The process continues by focusing in ever more detail on the keywords that match our trigeminal specific context outcome data that we should complete with an 'Abnormality' term. This term will perform the 2nd open loop with 5 specific items. At this point, one should cognitively make the effort to evaluate all 5 articles in order to be able to extrapolate some clinical or laboratory indications necessary for the decryption of the machine language code of the Central Nervous System. The evaluation of the articles revealed a phenomenon possibly present in some cases of bruxism, that of an altered excitability of the trigeminal system. Therefore, the term 'Excitability' was inserted in the network at the 3rd open loop.

- 3st loop open: In this phase the 'Excitability' data returned 3 very significant articles which highlight how the level of excitability of the trigeminal CNS can be tested through an electrophysiological technique called 'Recovery cycle' of the masseteric inhibitory reflex and signed in rcMIR. Obviously, in the case in question, the closure of the network loop was done on the first article in which this methodology is mentioned (the last article in chronological order was ours). From this article 'The excitability of the trigeminal motor system in sleep bruxism: a transcranial magnetic stimulation and brainstem reflex study' it is deduced that in patients who have reported signs and symptoms indicative of nocturnal bruxism (SB), there is an abnormal excitability of the trigeminal motor pathways. This increased excitability could result from altered modulation of inhibitory brainstem circuits and not from altered cortical mechanisms. The results support the idea that bruxism is mainly centrally mediated and involves subcortical structures.

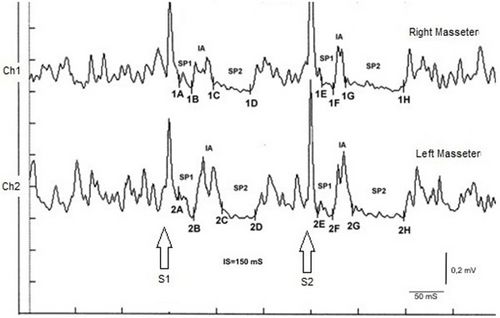

2nd Step: Recovery cycle of the Inhibitory Masseter Reflex

The recovery cycle of the Inhibitory Masseter Reflex (rcMIR) was studied by generating pairs of stimuli with identical characteristics, delivered percutaneously with a bipolar electrical stimulator positioned on the patient's face in the area of the mental nerve. The stimulation was produced using square wave electrical impulses, capable of evoking a well-defined inhibitory reflex composed of two silent periods (SP), called SP1 and SP2, separated by an interval of recovery of the EMG "Interposed Activity" ( IA). The first stimulus (S1) was considered as a conditioning stimulus and the second (S2) as a test stimulus. The inter-stimulus interval between S1 and S2 was set at 150 ms.

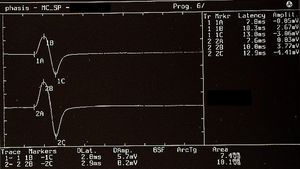

The subject was asked to clench his teeth to produce maximal EMG activity and to maintain the contraction for at least 3 s, with the help of visual and audio feedback. After 60 seconds of rest, the subject repeated the contraction 10 times. The EMG signal was recorded in directly rectified and averaged mode. The placement of the recording electrodes was the same as that used to record the jaw jerk and the preamplifier parameters are set to a time window width of 500ms, 200mV per division and a filter bandwidth of 50-1kHz. The latencies and durations of the SPs and the AI (Figure 1) were calculated as follows:

- To simplify the examination, the rcMIR was evoked by electrically stimulating the left side only. The EMG responses correspond to the EMG tracings of the right masseter (Ch1) and left masseter (Ch2). Thus, on the traces, each marker indicates the channel number, while the letters indicate the sequences of latencies.

- The S1 stimulus splits the acquisition into pre and post analysis and generates the SPs and the AI.

- The stimulus S2 delivered 150 ms from S1, called interstimulus (IS), evokes the second SP sequence and the IA.

- The SP of S1 and S2 are determined automatically by the software which positions the markers on the first and last minimum value elaborated on the traces for the generation of SP1 and SP2, and contextually calculates their duration. The IA duration is calculated between the last minimum value of SP1 and the first minimum value of SP2.

In the tested subject the S2 stimulus was able to evoke both SPs, while in a normal subject the S2 stimulus is normally able to evoke only the SP1 or at most one SP2 of reduced duration. As shown in Table 2, the duration of S2-evoked SP1 was found to be very stable, with no significant differences in the duration of S1-generated SP1 (Δ= -1ms for Ch1 and Δ= -2 ms for Ch2) while the from S2 on the right and left masseter (61 ms and 54 ms, respectively) was longer than that evoked by S1 (39 ms and 35 ms, respectively). The differences were +22 ms for Ch1 (right masseter) and +19 ms for Ch2 (left masseter). Consequently, the duration of the AI showed clear differences between S2 and S1. The duration of the S2-evoked AI was 12 ms vs. 23 ms of S1 stimulus for the right masseter (Ch1) and 17 ms vs 30 ms of S1 for the left masseter (Ch2) with a difference between the responses evoked by S2 minus S1 of -11 ms and -13 ms, respectively.

| Tabella 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of the positioning and measurements of the markers

for the recovery cycle of the Masseter Inhibitory Reflex ( rc MIR) | ||||

| S1 | S2 | |||

| EMG

traces |

Markers | Onset latency

S1 (msec) |

Markers | Onset latency

S1 (msec) |

| 1A | 11 | 1E | 12 | |

| Ch1

Right masseter muscle |

1B | 24 | 1F | 24 |

| 1C | 47 | 1G | 37 | |

| 1D | 86 | 1H | 98 | |

| 2A | 10 | 2E | 13 | |

| Ch2

Left masseter muscle |

2B | 26 | 2F | 27 |

| 2C | 56 | 2G | 44 | |

| 2D | 91 | 2H | 98 | |

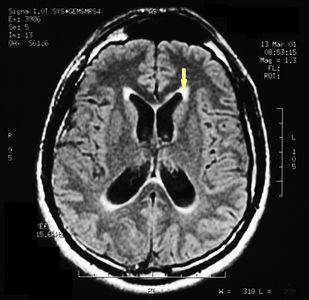

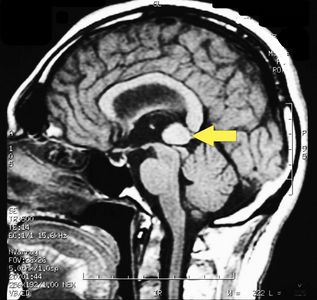

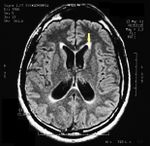

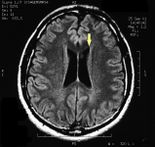

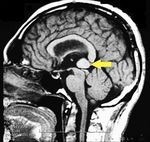

3rd Step: brain MNR

MRI of the brain, using Turbo Spin Echo, Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery, and Gradient Echo sequences, was conducted before and after intravenous administration of contrast medium. Results showed the presence of a roundish area of approximately 1.5 cm in diameter located in the vicinity of the quadrigeminal cistern at the level of the pineal gland. There was also a slight dilation of the supratentorial ventricular system, which appeared in the axis and was most evident in the proximity of the temporal horns, with a periventricular rim with a transependymal fluid absorption phenomenon.[1] The signal characteristics of the formation suggested a provisional diagnosis of pineal cavernoma. (Figures 2 and 3)

Final considerations

As we can see from the 'Visual Cognitive gallery', the neurological context is enriched by the contribution deriving from the decryption of the machine language through the rcMIR () test to definitively close the diagnosis with the MR report (). The diagnostic model Masticationpedia not only supports the doctor in complex diagnoses but above all it is an element of implementation of our basic knowledge . It will be useful to represent this cognitive interpretation by correlating it to the images of the assertions of the neurological context.

|

| |||||||

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to electrophysiologically document hyperexcitability of the trigeminal nervous system in a patient affected by pineal cavernoma with pronounced symptoms of OP and bruxism, and who was resistant to any pharmacological or odontological treatment.

We found evidence of activation and peripheral sensitization of the nociceptive fibers, the primary and secondary nociceptive neurons in the CNS, and the endogenous pain control systems, including both the inhibitory and facilitatory processes in our subject.

The concentration of extracellular glutamate in 13 patients affected by cavernous angioma[4] was reported to be increased in comparison with physiological concentrations. High levels of glutamate can cause negative effects on the brain through excitotoxic mechanisms, including degeneration of the superficial layer of the retina in a mouse after repeated administration of glutamate, termed “glutamate excitotoxicity”,[5] resulting from NMDA receptor hyperactivation .[6] In a study in which the trigeminal ganglion neurons were exposed to KCl, the calculated release of glutamate was 10 times greater than the basal level.[7] Further, a significant reduction in the release of potassium-induced glutamate was observed with addition of ω-agatoxin TK, a powerful P/Q calcium channel blocker, while the N-type calcium channel blocker ω-Cgtx conotoxin had a similar effect.[8] Nimodipine, an L-type calcium channel blocker, was also found to reduce the amount of potassium-induced glutamate release.[9] These studies suggest that the P/Q-, N-, and L-type calcium channels each mediate a significant fraction of depolarization-associated glutamate release.

Glutamate release is obviously a much broader and more complex phenomenon. NMDA, kainate, and AMPA ionotrophic receptors, and the metabotropic glutamate receptors, have been found in the superficial lamina of the trigeminal nucleus caudalis in mice.[10] NMDA and AMPA receptor antagonists can block the transmission of the nociceptive trigeminal-vascular signals [11][12] and reduce the high level of c-fos observed in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis following cisternal injection of capsaicin.[13] Furthermore, micro-injections of ω-agatoxin into the ventrolateral area of the periaqueductal gray cause a facilitatory response of nociceptive activity in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC) activated by tonic electrical stimulation of the supratentorial parietal dura, adjacent to the middle meningeal artery.[14]

This response can occur through antinociceptive and/or pronociceptive effects, because the presence of P/Q-type calcium channels is required at the synaptic level for the presynaptic action potentials to couple with the neurotransmitter release processes.[15] Of note, the pre-synaptic afferents in the PAG are positioned on GABAergic inhibitory interneurons and on descending projection neurons. Therefore, the facilitatory effect may be explained by an increased release of GABA, which would indirectly disinhibit the dorsal horn neurons, or by a direct pronociceptive mechanism.[16] These experimental results provide further understanding of the clinical manifestations of pain and central nervous system hyperexcitability found in cases of cerebral cavernous malformations.

Indeed, a blink reflex study on a 38-year-old patient with right hemicranial symptoms associated with a pontine cavernoma affecting the nucleus raphes magnus area revealed a reduction of the pain threshold and a persistent facilitation of the R2 response, with an onset latency difference of 4.4 ms less in the side displaying the symptoms [8]. This confirms a regulatory role for release of neurotransmitters by the nucleus raphes magnus, which exhibits a descending inhibitory control on the TNC [17]and on the entire antinociceptive mesencephalic complex.[18] Our results suggest a hyperexcitability of the trigeminal nervous system in our subject, as follows. First, we evoked a direct response of the trigeminal motor system (bR-MEPs) to provide a value for reference and for amplitude symmetry, as the direct response of the trigeminal motor branch was not affected by any conditioning. A comparison between the jaw jerk responses versus the ipsilateral responses of the R-MEPs showed a much higher amplitude ratio than in normal subjects [19] (Table 1). Therefore, these data indicate the presence of hyperexcitability of the trigeminal system.

The facilitatory effect on the masseter reflex could be indirect. The highest concentration of premotoneurons in the orofacial motor nuclei is found in the bulbar and pontine reticular formations adjacent to the motor nuclei themselves, where these are GABAergic, glycinergic, and glutamatergic-type premotoneurons.[20] In addition, the significant increase of the SP2 recovery cycle from S2 compared with the response from S1 (Table 2) corroborates the hypothesis of hyperexcitability of the trigeminal system. In an in vitro study performed on encephalic slices,[21] intracellular recording of interneurons of the peritrigeminal area (PeriV) surrounding the trigeminal motor nucleus (NVmt) and of the parvocellular reticular formation (PCRt) demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the adjacent areas could evoke both excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs). All the EPSPs induced by stimulation of the PeriV, PCRt, and NVmt were shown to be sensitive to ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists (DNQX and APV), while the IPSPs were sensitive to the GABA and glycine receptor antagonists, bicuculline and strychnine. The cells of this sample showed a long after-hyperpolarization (AHP).

In an electrophysiological study that analyzed a population of neurons and interneurons in the NVmt,[22] three types of AHP were seen: fast, slow, and biphasic. The majority of the motoneurons had a fast AHP (fAHP), whereas most of the interneurons had a slow AHP. The basic properties of these interneurons are similar to the previously described “last-order pre-motoneurons” in the PeriV,[23] suggesting that the interneurons in the NVmt are part of an interneuronal matrix surrounding the NVmt in which the motoneurons are inserted. In this last study, the authors describe the possibility, although rare, of interneurons also having an fAHP.

In our study, the increased duration of the SP2 from S2 invades the IA rather than expanding into the EMG reactivation after the silent period. The afferents for the SP2 descend their intra-axial process along the trigeminal spinal tract and connect with a polysynaptic chain of excitatory interneurons located in the reticular formation at the level of the pontocerebellar junction. The last interneuron in the chain is inhibitory, and sends ipsilateral and controlateral collaterals that ascend medially to the right and left spinal trigeminal complex to reach the trigeminal motoneurons.[24] The interneural sensitization in the rcMIR may be linked to a combination of the excitatory effect of glutamate, with a contribution from the intraneuronal fAHP, and to the disinhibition of the inhibitory processes due to the effect of glycine and GABA.

Overall, our data suggest that certain types of OP, at least those of a central origin, and bruxism are caused by a disruption and homeostatic imbalance of cerebral neurobiochemistry, particularly of the excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the trigeminal nervous system.

This gives rise to the following questions: Is there a correlation between OP and bruxism, and can bruxism be considered a clinical form of orofacial dystonia?

With respect to the correlation, a distinction should be made between central and peripheral OP on the basis of case history and clinical examination. The muscle discomfort of bruxism is mainly a peripheral phenomenon, resulting from muscle hyperfunction leading to destruction of the myofibrils and release of algogenic substances including myoglobin into bloodstream. By contrast, OP radiating to one or more areas of the face correlated with a clear manifestation of nocturnal or diurnal bruxism could be considered a central type disorder. In these cases, trigeminal electrophysical examinations are highly informative, particularly the rcMIR, blink reflex, JJr, and bR-MEPs, for a differential diagnosis between organic-type lesions of the CNS and functional-type diseases such as TMDs.

Thus, although bruxism and central OP can coexist, they are two independent symptoms, which is why many experimental and clinical studies fail to reach unequivocal conclusions.[25]

It is also possible that bruxism may be a clinical form of dystonia. Our data indicate that bruxism may be a clinical manifestation linked to a CNS neurotransmitter imbalance, and therefore should be considered a subclinical condition of orofacial dystonia or dystonic syndrome. Nevertheless, this phenomenon also appears in a transitory form in children and is resolved with the eruption of mixed dentition.[26][27]

Many studies and diagnostic research protocols, including the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), continue to appear in the field of OP and TMDs, although clear consensus has not yet been reached among the international scientific community.[28] The RDC should consider the patient as affected by a painful syndrome, and should tend towards the definition of a differential diagnosis between organic and/or functional pathologies.[29]

- ↑ Peter H Yang, Alison Almgren-Bell, Hongjie Gu, Anna V Dowling, Sangami Pugazenthi, Kimberly Mackey, Esther B Dupépé, Jennifer M Strahle. Etiology- and region-specific characteristics of transependymal cerebrospinal fluid flow. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2022 Aug 12;1-11. doi: 10.3171/2022.7.PEDS2246. Online ahead of print.

- ↑ Frisardi G. The use of transcranial stimulation in the fabrication of an occlusal splint. J Prosthet Dent, 1992, DOI: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90345-b

- ↑ G. Frisardi 1, P. Ravazzani, G. Tognola, F Grandori. Electric versus magnetic transcranial stimulation of the trigeminal system in healthy subjects. Clinical applications in gnathology. J Oral Rehabil.1997 Dec;24(12):920-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1997.00577.x.

- ↑ von Essen C, Rydenhag B, Nystrom B, Mozzi R, van Gelder N, Hamberger A. High levels of glycine and serine as a cause of the seizure symptoms of cavernous angiomas? J Neurochem. 1996;67(1):260–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Lau A, Tymianski M. Glutamate receptors, neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460(2):525–542. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0809-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Meldrum B, Garthwaite J. Excitatory amino acid neurotoxicity and neurodegenerative disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11(9):379–387. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90184-A. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Xiao Y, Richter JA, Hurley JH. Release of glutamate and CGRP from trigeminal ganglion neurons: role of calcium channels and 5-HT1 receptor signaling. Mol Pain. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ McCleskey EW, Fox AP, Feldman DH, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM, Tsien RW, Yoshikami D. Omega-conotoxin: direct and persistent blockade of specific types of calcium channels in neurons but not muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(12):4327–4331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hockerman GH, Johnson BD, Abbott MR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of high affinity phenylalkylamine block of L-type calcium channels in transmembrane segment IIIS6 and the pore region of the alpha1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(30):18759–18765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18759. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Young AB, Penney JB, Beitz AJ. Excitatory amino acid binding sites in the trigeminal principal sensory and spinal trigeminal nuclei of the rat. Neurosci Let. 1992;141(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90339-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Storer RJ, Goadsby PJ. Trigeminovascular nociceptive transmission involves N-methyl-D-aspartate and non-N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors. Neuroscience. 1999;90(4):1371–1376. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00536-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Goadsby PJ, Classey JD. Glutamatergic transmission in the trigeminal nucleus assessed with local blood flow. Brain Res. 2000;875(1–2):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Waeber C, Moskowitz MA, Cutrer FM, Sanchez Del Rio M, Mitsikostas DD. The NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 reduces capsaicin-induced c-fos expression within rat trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Pain. 1998;76(1–2):239–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Knight YE, Bartsch T, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. P/Q-type calcium-channel blockade in the periaqueductal gray facilitates trigeminal nociception: a functional genetic link for migraine? J Neurosci. 2002;22(5):RC213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18(2):89–98. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93882-X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Pan ZZ, Williams JT, Osborne PB. Opioid actions on single nucleus raphe magnus neurons from rat and guinea-pig in vitro. J Physiol. 1990;427:519–532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hentall ID. Interactions between brainstem and trigeminal neurons detected by cross-spectral analysis. Neuroscience. 2000;96(3):601–610. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00593-X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Jiang M, Behbehani MM. Physiological characteristics of the projection pathway from the medial preoptic to the nucleus raphe magnus of the rat and its modulation by the periaqueductal gray. Pain. 2001;94(2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00348-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Cruccu G, Berardelli A, Inghilleri M, Manfredi M. Functional organization of the trigeminal motor system in man. A neurophysiological study. Brain. 1989;112(5):1333–1350. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.5.1333. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Li YQ, Takada M, Kaneko T, Mizuno N. GABAergic and glycinergic neurons projecting to the trigeminal motor nucleus: a double labeling study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373(4):498–510. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960930)373:4<498::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bourque MJ, Kolta A. Properties and interconnections of trigeminal interneurons of the lateral pontine reticular formation in the rat. J Neurophys. 2001;86(5):2583–2596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ McDavid S, Verdier D, Lund JP, Kolta A. Electrical properties of interneurons found within the trigeminal motor nucleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(6):1136–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06413.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Kolta A, Westberg KG, Lund JP. Identification of brainstem interneurons projecting to the trigeminal motor nucleus and adjacent structures in the rabbit. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;19(3):175–195. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00061-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ongerboer de Visser BW, Cruccu G, Manfredi M, Koelman JH. Effects of brainstem lesions on the masseter inhibitory reflex. Functional mechanisms of reflex pathways. Brain. 1990;113(3):781–792. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.3.781. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Svensson P, Jadidi F, Arima T, Baad-Hansen L, Sessle BJ. Relationships between craniofacial pain and bruxism. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35(7):524–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01852.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Watts MW, Tan EK, Jankovic J. Bruxism and cranial-cervical dystonia: is there a relationship? Cranio. 1999;17(3):196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Monaco A, Ciammella NM, Marci MC, Pirro R, Giannoni M. The anxiety in bruxer child. A case–control study. Minerva Stomatol. 2002;51(6):247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Lobbezoo F, Visscher CM, Naeije M. Some remarks on the RDC/TMD Validation Project: report of an IADR/Toronto-2008 workshop discussion. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(10):779–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02091.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Frisardi G, Chessa G, Sau G, Frisardi F. Trigeminal electrophysiology: a 2 × 2 matrix model for differential diagnosis between temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]