Difference between revisions of "Are we sure to know everything?"

Tag: Manual revert |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{main menu}} | {{main menu}} | ||

{{Versions | {{Versions | ||

| en = Are we sure to know everything? | | en = Are we sure to know everything? | ||

| it = Siamo | | it = Siamo sicuri di sapere tutto? | ||

| fr = | | fr = Sommes-nous sûrs de tout savoir? | ||

| de = | | de = Wissen wir wirklich alles? | ||

| es = | | es = ¿Estamos seguros de saberlo todo? | ||

| pt = <!-- portoghese --> | | pt = <!-- portoghese --> | ||

| ru = <!-- russo --> | | ru = <!-- russo --> | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| ja = <!-- giapponese --> | | ja = <!-- giapponese --> | ||

}} | }} | ||

[[File:Question 2.jpg|left|150x150px]] | |||

We are approaching the conclusion of the first section of Masticationpedia which essentially had the task of representing the status quo of diagnostics in the field of Orofacial pain and Temporomandibular Disorders. We have also presented the first obstacles that arise in the face of a correct, detailed and rapid diagnosis but perhaps it escapes the researcher and clinician a little that there are also problems and limitations outside the clinical context for example when thinking about the order effect of the information presented to the doctor to make the diagnosis. Once we know this cognitive phenomenon, how can we represent it statistically? Unfortunately, classical statistics with the famous and inflated Bayes Theorem is not suitable because the variables are not compatible. For this reason, before moving on to the presentation of the last two patients we highlighted some underlying anomalies. | |||

=== | {{ArtBy| | ||

| autore = Gianni Frisardi | |||

| autore2 = Luca Fontana | |||

| autore3 = Flavio Frisardi | |||

| autore4 = | |||

| autore5 = | |||

| autore6 = | |||

| }} | |||

{{Bookind2}} | |||

< | === Introduction === | ||

During the previous chapters of Masticationpedia we wanted to highlight the diagnostic complexity in the field of Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) which sometimes hide much more serious neurological and/or systemic pathologies with a diagnostic course of decades. One of the most striking data that emerges from research in the literature is the high prevalence of TMD (30%-50%) throughout the world<ref>Ouanounou A, Goldberg M, Haas DA. Pharmacotherapy in '''Temporomandibular''' '''Disorders''': A '''Review'''. J Can Dent Assoc. 2017 Jul;83:h7.</ref> combined with their variability between clinical studies (3-20%)..<ref>Poveda Roda R, Bagan JV, Díaz Fernández JM, Hernández Bazán S, Jiménez Soriano Y. '''Review''' of '''temporomandibular''' '''joint''' pathology. Part I: classification, '''epidemiology''' and risk factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007 Aug 1;12(4):E292-8.</ref><ref>Türp JC, Schindler HJ.Schmerz. Chronic '''temporomandibular''' '''disorders''']. 2004 Apr;18(2):109-17. doi: 10.1007/s00482-003-0279-x.PMID: 15067530 </ref><ref>Fricton JR. The relationship of '''temporomandibular''' '''disorders''' and fibromyalgia: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2004 Oct;8(5):355-63. doi: 10.1007/s11916-996-0008-0.PMID: 15361319 </ref><ref>De Meyer MD, De Boever JA.The role of bruxism in the appearance of '''temporomandibular''' '''joint''' '''disorders'''].Rev Belge Med Dent (1984). 1997;52(4):124-38. PMID: 9709800 | |||

</ref> | |||

We ask ourselves, first of all: why is there so much variation in the prevalence of TMDs in the population between the various studies carried out in various parts of the world? Is it perhaps an error in the design of studies, statistical processes or knowledge? Be that as it may, all this has led the International Scientific Community to search for new paradigms to stem the diagnostic and therapeutic damage through a model called 'Research Diagnostic Criteria' and initialed as 'RDC'. Beyond the conceptual accuracy of the RDC created exclusively to distinguish the healthy from the TMDs sufferer, a topic that will be treated in detail in the next section of Masticationpedia, we found ourselves in the position of making diagnoses of serious pathologies in patients previously diagnosed as TMDs. | |||

This means that beyond the RDC, the diagnostic complexity in cases where there is a disorder of the masticatory system (clicks and crackles of the TMJ, bruxism, clenching, dental crossbite, etc.) together with painful orofacial symptoms, the issue can no longer be represented with a classic statistic like that of Bayes which essentially generated the positive predictive values of the RDC. | |||

So much so that it was necessary to organize a 'Consortium Network' replicated in various study meetings<ref>'''International RDC/TMD Consortium (2000–2002)''' | |||

Mark Drangsholt, Samuel Dworkin, James Fricton, Jean-Paul Goulet, Kimberly Huggins, Mike John, Iven Klineberg, Linda LeResche, Thomas List, Richard Ohrbach, Octavia Plesh, Eric Schiffman, Christian Stohler, Keson Beng-Choon Tan, Edmond Truelove, Adrian Yap, Efraim Winocur | Mark Drangsholt, Samuel Dworkin, James Fricton, Jean-Paul Goulet, Kimberly Huggins, Mike John, Iven Klineberg, Linda LeResche, Thomas List, Richard Ohrbach, Octavia Plesh, Eric Schiffman, Christian Stohler, Keson Beng-Choon Tan, Edmond Truelove, Adrian Yap, Efraim Winocur | ||

| Line 71: | Line 85: | ||

Per Alstergren, Jean-Paul Goulet, Frank Lobbezoo, Ambra Michelotti, Richard Ohrbach, Chris Peck, Eric Schiffman | Per Alstergren, Jean-Paul Goulet, Frank Lobbezoo, Ambra Michelotti, Richard Ohrbach, Chris Peck, Eric Schiffman | ||

International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR</ref> | International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR</ref> which essentially reach the following conclusion by R. Ohrbach and S.F. Dworkin.<ref name=":2">R. Ohrbach and S.F. Dworkin. The Evolution of TMD Diagnosis. Past, Present, Future Monitoring Editor: Ronald Dubner. J Dent Res. 2016 Sep; 95(10): 1093–1101. Published online 2016 Jun 16. doi: 10.1177/0022034516653922 PMCID: PMC5004241, PMID: 27313164 | ||

</ref> | |||

</ | <blockquote>A final theme is that our understanding of specific TMJ disorders lags behind that of pain disorders. The collective implication of these themes is that further research and development will benefit from a programmatic approach inclusive of the multiple directions described here as well as countless others that exist outside the current consortium framework.</blockquote> | ||

The aim of Masticationpedia is and will be over time, precisely, the request expressed by Ohrbach and S.F. Dworkin,<ref name=":2" /> namely: | |||

{{q2|........further research and development will benefit from a programmatic approach that is inclusive of the multiple directions described here as well as countless others that exist outside the current consortium framework|Let's look at some relevant passages}} | |||

==== | ==== Prevalence of TMDs ==== | ||

The prevalence of temporomandibular disorder (TMDs) symptoms varies significantly between populations. | |||

A recent systematic review indicated that in the general population the prevalence of having at least one clinical sign of TMD varies between 5 and 60%.<ref>Ryan J, Akhter R, Hassan N, Hilton G, Wickham J, Ibaragi S. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorder in the general population : a systematic review. Adv Dent Oral Health. 2019;10:1–13. doi: 10.19080/ADOH.2019.10.555787.</ref> However, pain in the temporomandibular region is a common clinical sign, occurring in approximately 10% of the adult population.<ref>Al-Jundi MA, John MT, Setz JM, Szentpétery A, Kuss O. Meta-analysis of treatment need for temporomandibular disorders in adult nonpatients. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22:97–107.</ref> Primary headaches (migraine and tension-type headache [TTH]), however, affect more than 2.5 billion individuals worldwide. A recent global study ranked headaches as the second leading cause of years lost to disability, after low back pain.<ref>GBD Diseases and injuries collaborators (2020) global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2019;396:1204–1222</ref> Globally, the number of individuals suffering from migraine and TTH in 2017 was estimated to be 1.3 and 2.3 billion with a prevalence of 15% and 16%, respectively.<ref>James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.</ref> | |||

These data already indicate a certain uncertainty in the numbers, an uncertainty which, as we will see later, becomes dramatically conditioning in Bayesian predictability models. | |||

Furthermore, most of the previous studies on the association of TMD-related pain and headache have been based on 'Frequencyist' statistics, models which, compared to the Bayesian approach, suffer from some limitations, especially the dependence on large samples so that effect sizes are precisely determined.<ref name=":0">Buchinsky FJ, Chadha NK. To P or not to P: backing Bayesian statistics. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(6):915–918. doi: 10.1177/0194599817739260.</ref><blockquote>According to Javed Ashraf et al.<ref name=":1">Javed Ashraf, Matti Närhi, Anna Liisa Suominen, Tuomas Saxlin. Association of temporomandibular disorder-related pain with severe headaches-a Bayesian view. Clin Oral Investing. 2022 Jan;26(1):729-738. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04051-y. Epub 2021 Jul 5.</ref> contrary to the 'Frequencyist' methodology, Bayesian statistics does not provide a (fixed) result value but rather an interval containing the regression coefficient.<ref>Depaoli S, van de Schoot R. Bayesian analyses: where to start and what to report. Eur Heal Psychol. 2014;16:75–84.</ref> These intervals, called confidence intervals (CI), assign a probability to the best estimate and to all possible values of the parameter estimates.<ref name=":0" /></blockquote>In the study by Javed Ashraf et al.<ref name=":1" /> the authors using Bayesian methodology, attempted to verify the existence of the correlation between TMD-related pain with severe headaches (migraine and TTH) over an 11-year follow-up period. The Health 2000 survey, conducted in 2000 and 2001, included 9922 invited participants aged 18 years and older living in mainland Finland.<ref>Aromaa A, Koskinen S (2004) Health and functional capacity in Finland. Baseline results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Publications of the National Public Health Institute B12/2004. Helsinki</ref> The prospective association of mTMD at baseline with the presence of TTH at follow-up found in the present study is in line with previous epidemiological, clinical and physiological evidence. Previous epidemiological studies have shown an association between TMD-related pain and TTH.<ref>Ciancaglini R, Radaelli G. The relationship between headache and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder in the general population. J Dent. 2001;29:93–98. doi: 10.1016/S0300-5712(00)00042-7</ref> Clinically, TMD-related pain and TTH share a combination of distinct signs and symptoms in the head and facial region, particularly evident regarding mTMD and TTH. These common clinical features include tenderness on palpation of the masticatory muscles in the case of mTMD and of the pericranial muscles in the case of TTH during the active phases of both conditions.<ref>Bendtsen L, Ashina S, Moore A, Steiner TJ. Muscles and their role in episodic tension-type headache: implications for treatment. Eur J Pain. 2016;20:166–175. doi: 10.1002/ejp.748.</ref> Other clinical intersections between mTMD and TTH include age of subjects regarding peak prevalence,<ref>Costa Y-M, Porporatti A-L, Calderon P-S, Conti P-C-R, Bonjardim L-R. Can palpation-induced muscle pain pattern contribute to the differential diagnosis among temporomandibular disorders, primary headaches phenotypes and possible bruxism? Med oral, Patol oral y cirugía bucal. 2016;21:e59–65. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20826.</ref> pain intensity, pharmacotherapy,<ref>Neblett R, Cohen H, Choi Y, Hartzell MM, Williams M, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. The central sensitization inventory (CSI): establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain. 2013;14:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.012.</ref> and even non-pharmacological treatment.<ref>Fernández-De-Las-Peñas C, Cuadrado ML. Physical therapy for headaches. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:1134–1142. doi: 10.1177/0333102415596445.</ref> Despite some clinical similarities and overlap, both mTMD and TTH are distinct disease entities and Javed Ashraf<ref name=":1" /> elegantly concludes: | |||

{{q2|Although the mix of similarities may require close interdisciplinary cooperation between specialties (dentistry vs neurology), vigilance should also be exercised regarding the distinction between these two pathological entities during their treatment.|'Interdisciplinarity' means 'Context'}} | |||

==== Contexts ==== | |||

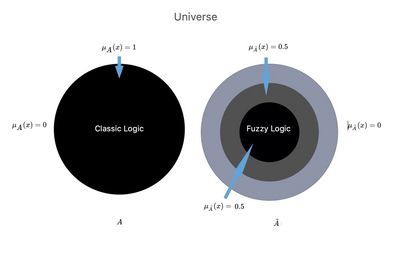

In the previous chapters of Masticationpedia, when describing the diagnostic complexity we took into consideration a fact that will be essential: the contexts. We have seen how a symptomatic or asymptomatic sick person places himself before the doctor who, listening to his story, tries to reconstruct the progress of the 'state' of the organic system to reach a certain diagnosis. At the same time, however, we also considered the enormous distance in clinical scientific knowledge between a context, the dental one, and the neurological one. These contexts employing a formal logic arrive at the conviction of their diagnostic reason. The assumption is that the assertions that contribute to building this certainty are very different between contexts. For this reason in the chapter '[[Fuzzy language logic]]' we considered a set <math>\tilde{A}</math> and a membership function <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {\tilde {A}}}(x)</math>. | |||

We choose - as a formalism - to represent a fuzzy set with the 'tilde' <math>\tilde{A}</math>. A fuzzy set is a set in which the elements have a 'degree' of membership (consistent with fuzzy logic), some may be included in the set at 100%, others at lower percentages. This degree of membership is mathematically represented by the function called 'Membership function'<math>\mu_{\displaystyle {\tilde {A}}}(x)</math>. | |||

Let's imagine that <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {\tilde {A}}}(x)</math> it represents a context and that it is a continuous function defined in the range <math>[0;1]</math> where: | |||

*<math>\mu_ {\tilde {A}}(x) = 1\rightarrow </math>if it is totally contained in <math>A</math> (these points are called 'nucleus', they indicate the plausible values of the predicate). | |||

*<math>\mu_ {\tilde {A}}(x) = 0\rightarrow </math> if <math>x</math> it is not contained in <math>A</math> | |||

*<math>0<\mu_ {\tilde {A}}(x) < 1 \;\rightarrow </math> if <math>x</math> it is partially contained in <math>A</math> (these points are called 'Support set' <nowiki/>and indicate the possible values of the predicate possible predicate values). | |||

The '''support set''' of a fuzzy set is defined as the area in which the degree of membership results <math>0<\mu_ {\tilde {A}}(x) < 1</math>; the nucleus or core is instead defined as the area in which the degree of belonging takes on value <math>\mu_ {\tilde {A}}(x) = 1</math>. The 'Support set' represents the values of the predicate considered ''possible'', while the ''''core'''<nowiki/>' represents those considered most ''plausible''. | |||

If <math>{A}</math> it represented a set in the ordinary sense of the term or in the logic of the classical language previously described, its membership function could only take on the values <math>1</math> or <math>0</math> (Figure 1, <math>{A}</math>) <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 1 \; \lor \;\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 0</math> depending on whether element <math>0</math> belongs to the whole or not, as considered. | |||

[[File:Fuzzy2.jpg|alt=|thumb|400x400px|'''Figure 1:''' Representation of the comparison between a classical and fuzzy ensemble.]] | |||

Let's imagine, now, that in the Universe of Science <math>U</math> there exist two parallel worlds or contexts <math>{A}</math> and <math>\tilde{A}</math> in which our patient Mary Poppins happens to find herself ([[1° Clinical case: Hemimasticatory spasm|see chapter]]). | |||

<math>{A}=</math> | <math>{A}=</math> A world or scientific context, the so-called 'well defined', of the logic of classical language, in which the doctor has an absolute basic scientific knowledge <nowiki>''</nowiki><math>KB</math> with a clear dividing line that depicts the area of its own context that we call <math>KB_c</math> (Knowledge Basic contest). In this Universe we are faced with a single world or context (let's consider the dental one) and the answers can only be <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 1 \; \lor \;\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 0</math> and therefore TMDs or noTMDs. | ||

<math>\tilde{A}=</math> | <math>\tilde{A}=</math> In the other world or scientific context called 'Fuzzy Logic', we are represented with a world or context of union between the subset <math>{A}</math> in <math>\tilde{A}</math>such a way as to be able to state that the worlds partially merge and consequently also the contexts are linked to give life to one <math>KB_c</math> of the unified contexts. | ||

We will note the following deductions: | |||

* '''Classical logic''' in the dental context <math>{A}</math> in which only a logical process that gives <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 1 </math> as a result will be possible, i.e. <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 0 </math> the data range being <math>D=\{\delta_1,\dots,\delta_4\}</math> reduced to basic knowledge <math>KB</math> (dental scientific/clinical context) as a whole <math>{A}</math>. This means that outside the dental world or context there is a void and that the term set theory is written exactly <math>\mu_{\displaystyle {{A}}}(x)= 0 </math>and that it is synonymous with 'diagnostic risk'. | |||

* '''Fuzzy logic''' in the world <math>\tilde{A}</math> in which not only the basic knowledge <math>KB</math> of the dental context but also those partially acquired from the neurophysiological world are represented, we have that the membership function will be determined by the summation of the two contexts <math>{A}</math> and <math>\tilde{A}</math>. In this scenario the membership function will always be within the range <math>0<\mu_ {\tilde {A}}(x) < 1</math> but the output data will correspond to the sum of the two contexts, obviously decreasing the diagnostic risk. | |||

{{q2|Well then we are already one step ahead. We understood that beyond the RDC model, contexts are fundamental for diagnosis.|.....yes, certainly a small step forward if there wasn't another little-considered obstacle, that of the 'Information Order' of the contexts}} | |||

==== Order of information==== | |||

The order of information plays a crucial role in the process of updating beliefs over time. In fact, the presence of order effects makes a classical or Bayesian approach to inference difficult. | |||

Suppose we are interested in evaluating the probability of a hypothesis <math>H</math> given two pieces of information <math>A</math> and <math>B</math>. Since classical probability obeys the commutative property, we have the following model: | |||

Let's imagine a cognitive diagnostic decision that a doctor takes when visiting a patient with Orofacial Pain, who, only after a medical history and a detailed clinical functional analysis of the masticatory system in which occlusal discrepancies emerge '<math>A</math>', is presented with electrophysiological laboratory data showing an asymmetry of the trigeminal responses '<math>B</math>' from which to formulate a first hypothesis <math>H</math> of DTMs. the predictability that this hypothesis is true has a probability that derives from Bayes' Therem read as follows: | |||

The probability of the hypothesis <math>H</math> that a patient is affected by TMDs if a first event <math>A</math> (occlusal discrepancies) and a second event <math>B</math> (asymmetry of trigeminal responses) coexists is given by: | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

P(H|B\cap A)=p(H|B)\cdot \left ( \frac{p(A|H\cap B)}{p(A|B)} \right )=P(H|A\cap B)=p(H|A)\cdot \left ( \frac{p(B|H\cap A)}{p(B|A)} \right )</math> | P(H|B\cap A)=p(H|B)\cdot \left ( \frac{p(A|H\cap B)}{p(A|B)} \right )=P(H|A\cap B)=p(H|A)\cdot \left ( \frac{p(B|H\cap A)}{p(B|A)} \right )</math> | ||

This means that for Bayes the probability of being ill with a certain disease (Positive Predictive Value) does not change if the order of presentation of the information is reversed since in Bayes the variables <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> commute because they are compatible. As mentioned, if we change the order of presentation of the information the result does not change while at a cognitive decision-making level things are not exactly like that. Changing the order of presentation of the information can completely change the hypothesis, moving towards a diagnosis of neuropathy rather than TMD. | |||

{{ | {{q2|So how can the problem be solved?|......with the usual Hamletic doubt: who says that the asymmetry of the trigeminal responses are compatible with a TMD?}} | ||

In quantum theory, events can be defined as compatible or incompatible. In the case where all events are compatible, quantum probability is identical to classical probability. Deciding when two events should be treated as compatible or incompatible is an important research question. In a very interesting article Jennifer S. Trueblood and Jerome R. Busemeyer<ref>Jennifer S. Trueblood, Jerome R. Busemeyer. A Quantum Probability Account of Order Effects in Inference. Cognitive Science Volume 35, Issue 8 p. 1518-1552. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01197.x</nowiki> | |||

</ref> represented the phenomenon of the information order effect by concluding that Cognitive models based on the principles of quantum probability have the potential to explain paradoxical phenomena that occur in science cognitive. Previously, quantum models have been used to account for violations of rational principles of decision making,<ref>Pothos, E. M., & Busemeyer, J. R. (2009). A quantum probability explanation for violations of “rational” decision theory. ''Proceedings of the Royal Society B'', 276(1165), 2171–2178.</ref> paradoxes of conceptual combination,<ref>Aerts, D. (2009). Quantum structure in cognition. ''Journal of Mathematical Psychology'', 53, 314–348</ref> human judgments<ref>Khrennikov, A. Y. (2004). Information dynamics in cognitive, psychological, social and anomalous phenomena. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.</ref> and perception<ref>Atmanspacher, H., Filk, T., & Romer, H. (2004). Quantum zero features of bistable perception. ''Biological Cybernetics'', 90, 33–40.</ref> and that, however, the quantum inference model can fit the task data perfectly medical decision-making by Bergus et al. (1998).<ref>Bergus, G. R., Chapman, G. B., Levy, B. T., Ely, J. W., & Oppliger, R. A. (1998). Clinical diagnosis and order of information. ''Medical Decision Making'', 18, 412–417.</ref> | |||

{{q2|Are we still sure we know everything?|...let's see what happens to our last two patients}} | |||

{{bib}} | {{bib}} | ||

Revision as of 11:08, 22 February 2024

Are we sure to know everything?

We are approaching the conclusion of the first section of Masticationpedia which essentially had the task of representing the status quo of diagnostics in the field of Orofacial pain and Temporomandibular Disorders. We have also presented the first obstacles that arise in the face of a correct, detailed and rapid diagnosis but perhaps it escapes the researcher and clinician a little that there are also problems and limitations outside the clinical context for example when thinking about the order effect of the information presented to the doctor to make the diagnosis. Once we know this cognitive phenomenon, how can we represent it statistically? Unfortunately, classical statistics with the famous and inflated Bayes Theorem is not suitable because the variables are not compatible. For this reason, before moving on to the presentation of the last two patients we highlighted some underlying anomalies.

Introduction

During the previous chapters of Masticationpedia we wanted to highlight the diagnostic complexity in the field of Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) which sometimes hide much more serious neurological and/or systemic pathologies with a diagnostic course of decades. One of the most striking data that emerges from research in the literature is the high prevalence of TMD (30%-50%) throughout the world[1] combined with their variability between clinical studies (3-20%)..[2][3][4][5]

We ask ourselves, first of all: why is there so much variation in the prevalence of TMDs in the population between the various studies carried out in various parts of the world? Is it perhaps an error in the design of studies, statistical processes or knowledge? Be that as it may, all this has led the International Scientific Community to search for new paradigms to stem the diagnostic and therapeutic damage through a model called 'Research Diagnostic Criteria' and initialed as 'RDC'. Beyond the conceptual accuracy of the RDC created exclusively to distinguish the healthy from the TMDs sufferer, a topic that will be treated in detail in the next section of Masticationpedia, we found ourselves in the position of making diagnoses of serious pathologies in patients previously diagnosed as TMDs.

This means that beyond the RDC, the diagnostic complexity in cases where there is a disorder of the masticatory system (clicks and crackles of the TMJ, bruxism, clenching, dental crossbite, etc.) together with painful orofacial symptoms, the issue can no longer be represented with a classic statistic like that of Bayes which essentially generated the positive predictive values of the RDC.

So much so that it was necessary to organize a 'Consortium Network' replicated in various study meetings[6][7][8][9][10][11] which essentially reach the following conclusion by R. Ohrbach and S.F. Dworkin.[12]

A final theme is that our understanding of specific TMJ disorders lags behind that of pain disorders. The collective implication of these themes is that further research and development will benefit from a programmatic approach inclusive of the multiple directions described here as well as countless others that exist outside the current consortium framework.

The aim of Masticationpedia is and will be over time, precisely, the request expressed by Ohrbach and S.F. Dworkin,[12] namely:

(Let's look at some relevant passages)

Prevalence of TMDs

The prevalence of temporomandibular disorder (TMDs) symptoms varies significantly between populations.

A recent systematic review indicated that in the general population the prevalence of having at least one clinical sign of TMD varies between 5 and 60%.[13] However, pain in the temporomandibular region is a common clinical sign, occurring in approximately 10% of the adult population.[14] Primary headaches (migraine and tension-type headache [TTH]), however, affect more than 2.5 billion individuals worldwide. A recent global study ranked headaches as the second leading cause of years lost to disability, after low back pain.[15] Globally, the number of individuals suffering from migraine and TTH in 2017 was estimated to be 1.3 and 2.3 billion with a prevalence of 15% and 16%, respectively.[16]

These data already indicate a certain uncertainty in the numbers, an uncertainty which, as we will see later, becomes dramatically conditioning in Bayesian predictability models.

Furthermore, most of the previous studies on the association of TMD-related pain and headache have been based on 'Frequencyist' statistics, models which, compared to the Bayesian approach, suffer from some limitations, especially the dependence on large samples so that effect sizes are precisely determined.[17]

According to Javed Ashraf et al.[18] contrary to the 'Frequencyist' methodology, Bayesian statistics does not provide a (fixed) result value but rather an interval containing the regression coefficient.[19] These intervals, called confidence intervals (CI), assign a probability to the best estimate and to all possible values of the parameter estimates.[17]

In the study by Javed Ashraf et al.[18] the authors using Bayesian methodology, attempted to verify the existence of the correlation between TMD-related pain with severe headaches (migraine and TTH) over an 11-year follow-up period. The Health 2000 survey, conducted in 2000 and 2001, included 9922 invited participants aged 18 years and older living in mainland Finland.[20] The prospective association of mTMD at baseline with the presence of TTH at follow-up found in the present study is in line with previous epidemiological, clinical and physiological evidence. Previous epidemiological studies have shown an association between TMD-related pain and TTH.[21] Clinically, TMD-related pain and TTH share a combination of distinct signs and symptoms in the head and facial region, particularly evident regarding mTMD and TTH. These common clinical features include tenderness on palpation of the masticatory muscles in the case of mTMD and of the pericranial muscles in the case of TTH during the active phases of both conditions.[22] Other clinical intersections between mTMD and TTH include age of subjects regarding peak prevalence,[23] pain intensity, pharmacotherapy,[24] and even non-pharmacological treatment.[25] Despite some clinical similarities and overlap, both mTMD and TTH are distinct disease entities and Javed Ashraf[18] elegantly concludes:

('Interdisciplinarity' means 'Context')

Contexts

In the previous chapters of Masticationpedia, when describing the diagnostic complexity we took into consideration a fact that will be essential: the contexts. We have seen how a symptomatic or asymptomatic sick person places himself before the doctor who, listening to his story, tries to reconstruct the progress of the 'state' of the organic system to reach a certain diagnosis. At the same time, however, we also considered the enormous distance in clinical scientific knowledge between a context, the dental one, and the neurological one. These contexts employing a formal logic arrive at the conviction of their diagnostic reason. The assumption is that the assertions that contribute to building this certainty are very different between contexts. For this reason in the chapter 'Fuzzy language logic' we considered a set and a membership function .

We choose - as a formalism - to represent a fuzzy set with the 'tilde' . A fuzzy set is a set in which the elements have a 'degree' of membership (consistent with fuzzy logic), some may be included in the set at 100%, others at lower percentages. This degree of membership is mathematically represented by the function called 'Membership function'.

Let's imagine that it represents a context and that it is a continuous function defined in the range where:

- if it is totally contained in (these points are called 'nucleus', they indicate the plausible values of the predicate).

- if it is not contained in

- if it is partially contained in (these points are called 'Support set' and indicate the possible values of the predicate possible predicate values).

The support set of a fuzzy set is defined as the area in which the degree of membership results ; the nucleus or core is instead defined as the area in which the degree of belonging takes on value . The 'Support set' represents the values of the predicate considered possible, while the 'core' represents those considered most plausible.

If it represented a set in the ordinary sense of the term or in the logic of the classical language previously described, its membership function could only take on the values or (Figure 1, ) depending on whether element belongs to the whole or not, as considered.

Let's imagine, now, that in the Universe of Science there exist two parallel worlds or contexts and in which our patient Mary Poppins happens to find herself (see chapter).

A world or scientific context, the so-called 'well defined', of the logic of classical language, in which the doctor has an absolute basic scientific knowledge '' with a clear dividing line that depicts the area of its own context that we call (Knowledge Basic contest). In this Universe we are faced with a single world or context (let's consider the dental one) and the answers can only be and therefore TMDs or noTMDs.

In the other world or scientific context called 'Fuzzy Logic', we are represented with a world or context of union between the subset in such a way as to be able to state that the worlds partially merge and consequently also the contexts are linked to give life to one of the unified contexts.

We will note the following deductions:

- Classical logic in the dental context in which only a logical process that gives as a result will be possible, i.e. the data range being reduced to basic knowledge (dental scientific/clinical context) as a whole . This means that outside the dental world or context there is a void and that the term set theory is written exactly and that it is synonymous with 'diagnostic risk'.

- Fuzzy logic in the world in which not only the basic knowledge of the dental context but also those partially acquired from the neurophysiological world are represented, we have that the membership function will be determined by the summation of the two contexts and . In this scenario the membership function will always be within the range but the output data will correspond to the sum of the two contexts, obviously decreasing the diagnostic risk.

(.....yes, certainly a small step forward if there wasn't another little-considered obstacle, that of the 'Information Order' of the contexts)

Order of information

The order of information plays a crucial role in the process of updating beliefs over time. In fact, the presence of order effects makes a classical or Bayesian approach to inference difficult.

Suppose we are interested in evaluating the probability of a hypothesis given two pieces of information and . Since classical probability obeys the commutative property, we have the following model:

Let's imagine a cognitive diagnostic decision that a doctor takes when visiting a patient with Orofacial Pain, who, only after a medical history and a detailed clinical functional analysis of the masticatory system in which occlusal discrepancies emerge '', is presented with electrophysiological laboratory data showing an asymmetry of the trigeminal responses '' from which to formulate a first hypothesis of DTMs. the predictability that this hypothesis is true has a probability that derives from Bayes' Therem read as follows:

The probability of the hypothesis that a patient is affected by TMDs if a first event (occlusal discrepancies) and a second event (asymmetry of trigeminal responses) coexists is given by:

This means that for Bayes the probability of being ill with a certain disease (Positive Predictive Value) does not change if the order of presentation of the information is reversed since in Bayes the variables and commute because they are compatible. As mentioned, if we change the order of presentation of the information the result does not change while at a cognitive decision-making level things are not exactly like that. Changing the order of presentation of the information can completely change the hypothesis, moving towards a diagnosis of neuropathy rather than TMD.

(......with the usual Hamletic doubt: who says that the asymmetry of the trigeminal responses are compatible with a TMD?)

In quantum theory, events can be defined as compatible or incompatible. In the case where all events are compatible, quantum probability is identical to classical probability. Deciding when two events should be treated as compatible or incompatible is an important research question. In a very interesting article Jennifer S. Trueblood and Jerome R. Busemeyer[26] represented the phenomenon of the information order effect by concluding that Cognitive models based on the principles of quantum probability have the potential to explain paradoxical phenomena that occur in science cognitive. Previously, quantum models have been used to account for violations of rational principles of decision making,[27] paradoxes of conceptual combination,[28] human judgments[29] and perception[30] and that, however, the quantum inference model can fit the task data perfectly medical decision-making by Bergus et al. (1998).[31]

(...let's see what happens to our last two patients)

- ↑ Ouanounou A, Goldberg M, Haas DA. Pharmacotherapy in Temporomandibular Disorders: A Review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2017 Jul;83:h7.

- ↑ Poveda Roda R, Bagan JV, Díaz Fernández JM, Hernández Bazán S, Jiménez Soriano Y. Review of temporomandibular joint pathology. Part I: classification, epidemiology and risk factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007 Aug 1;12(4):E292-8.

- ↑ Türp JC, Schindler HJ.Schmerz. Chronic temporomandibular disorders]. 2004 Apr;18(2):109-17. doi: 10.1007/s00482-003-0279-x.PMID: 15067530

- ↑ Fricton JR. The relationship of temporomandibular disorders and fibromyalgia: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2004 Oct;8(5):355-63. doi: 10.1007/s11916-996-0008-0.PMID: 15361319

- ↑ De Meyer MD, De Boever JA.The role of bruxism in the appearance of temporomandibular joint disorders].Rev Belge Med Dent (1984). 1997;52(4):124-38. PMID: 9709800

- ↑ International RDC/TMD Consortium (2000–2002) Mark Drangsholt, Samuel Dworkin, James Fricton, Jean-Paul Goulet, Kimberly Huggins, Mike John, Iven Klineberg, Linda LeResche, Thomas List, Richard Ohrbach, Octavia Plesh, Eric Schiffman, Christian Stohler, Keson Beng-Choon Tan, Edmond Truelove, Adrian Yap, Efraim Winocur NIDCR

- ↑ Miami Consensus Workshop (2009) Workgroup 1: Gary Anderson, Yoly Gonzalez, Jean-Paul Goulet, Rigmor Jensen, Bill Maixner, Ambra Michelotti, Greg Murray, Corine Visscher Workgroup 2: Sharon Brooks, Lars Hollender, Frank Lobbezoo, John Look, Sandro Palla, Arne Petersson, Eric Schiffman Workgroup 3: Werner Ceusters, Antoon deLaat, Reny deLeeuw, Mark Drangsholt, Dominic Ettlin, Charly Gaul, Thomas List, Don Nixdorf, Joanna Zakrzewska Workgroup 4: Sam Dworkin, Louis Goldberg, Jennifer Haythornthwaite, Mike John, Richard Ohrbach, Paul Pionchon, Marylee van der Meulen At large: Terri Cowley, Don Denucci, John Kusiak, Barry Smith, Peter Svensson International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group of the International Association for the Study of Pain Canadian Institute for Health Research National Center for Biomedical Ontology Medtech

- ↑ San Diego Consensus Workshop (2011) Workgroup 1: Gary Anderson, Reny deLeeuw, Jean-Paul Goulet, Rigmor Jensen, Frank Lobbezoo, Chris Peck, Arne Petersson, Eric Schiffman Workgroup 2: Justin Durham, Dominic Ettlin, Ambra Michelotti, Richard Ohrbach, Sandro Palla, Karen Raphael, Yoshihiro Tsukiyama, Corine Visscher Workgroup 3: Raphael Benoliel, Brian Cairns, Mark Drangsholt, Malin Ernberg, Lou Goldberg, Bill Maixner, Don Nixdorf, Doreen Pfau, Peter Svensson International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR International Association for the Study of Pain Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group Canadian Institute for Health Research

- ↑ Iguacu Falls (Brazil) Workshop (2012) Workgroup 1: Reny deLeeuw, Jean-Paul Goulet, Frank Lobbezoo, Chris Peck, Eric Schiffman, Thomas List Workgroup 2: Justin Durham, Dominik Ettlin, Richard Ohrbach International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR

- ↑ Seattle Symposium (2013) Raphael Benoliel, Brian Cairns, Werner Ceusters, Justin Durham, Eli Eliav, Ambra Michelotti, Richard Ohrbach, Karen Raphael International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR

- ↑ Cape Town Symposium (2014) Per Alstergren, Jean-Paul Goulet, Frank Lobbezoo, Ambra Michelotti, Richard Ohrbach, Chris Peck, Eric Schiffman International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and IADR

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 R. Ohrbach and S.F. Dworkin. The Evolution of TMD Diagnosis. Past, Present, Future Monitoring Editor: Ronald Dubner. J Dent Res. 2016 Sep; 95(10): 1093–1101. Published online 2016 Jun 16. doi: 10.1177/0022034516653922 PMCID: PMC5004241, PMID: 27313164

- ↑ Ryan J, Akhter R, Hassan N, Hilton G, Wickham J, Ibaragi S. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorder in the general population : a systematic review. Adv Dent Oral Health. 2019;10:1–13. doi: 10.19080/ADOH.2019.10.555787.

- ↑ Al-Jundi MA, John MT, Setz JM, Szentpétery A, Kuss O. Meta-analysis of treatment need for temporomandibular disorders in adult nonpatients. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22:97–107.

- ↑ GBD Diseases and injuries collaborators (2020) global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2019;396:1204–1222

- ↑ James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Buchinsky FJ, Chadha NK. To P or not to P: backing Bayesian statistics. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(6):915–918. doi: 10.1177/0194599817739260.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Javed Ashraf, Matti Närhi, Anna Liisa Suominen, Tuomas Saxlin. Association of temporomandibular disorder-related pain with severe headaches-a Bayesian view. Clin Oral Investing. 2022 Jan;26(1):729-738. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04051-y. Epub 2021 Jul 5.

- ↑ Depaoli S, van de Schoot R. Bayesian analyses: where to start and what to report. Eur Heal Psychol. 2014;16:75–84.

- ↑ Aromaa A, Koskinen S (2004) Health and functional capacity in Finland. Baseline results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Publications of the National Public Health Institute B12/2004. Helsinki

- ↑ Ciancaglini R, Radaelli G. The relationship between headache and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder in the general population. J Dent. 2001;29:93–98. doi: 10.1016/S0300-5712(00)00042-7

- ↑ Bendtsen L, Ashina S, Moore A, Steiner TJ. Muscles and their role in episodic tension-type headache: implications for treatment. Eur J Pain. 2016;20:166–175. doi: 10.1002/ejp.748.

- ↑ Costa Y-M, Porporatti A-L, Calderon P-S, Conti P-C-R, Bonjardim L-R. Can palpation-induced muscle pain pattern contribute to the differential diagnosis among temporomandibular disorders, primary headaches phenotypes and possible bruxism? Med oral, Patol oral y cirugía bucal. 2016;21:e59–65. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20826.

- ↑ Neblett R, Cohen H, Choi Y, Hartzell MM, Williams M, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. The central sensitization inventory (CSI): establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain. 2013;14:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.012.

- ↑ Fernández-De-Las-Peñas C, Cuadrado ML. Physical therapy for headaches. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:1134–1142. doi: 10.1177/0333102415596445.

- ↑ Jennifer S. Trueblood, Jerome R. Busemeyer. A Quantum Probability Account of Order Effects in Inference. Cognitive Science Volume 35, Issue 8 p. 1518-1552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01197.x

- ↑ Pothos, E. M., & Busemeyer, J. R. (2009). A quantum probability explanation for violations of “rational” decision theory. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 276(1165), 2171–2178.

- ↑ Aerts, D. (2009). Quantum structure in cognition. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 53, 314–348

- ↑ Khrennikov, A. Y. (2004). Information dynamics in cognitive, psychological, social and anomalous phenomena. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

- ↑ Atmanspacher, H., Filk, T., & Romer, H. (2004). Quantum zero features of bistable perception. Biological Cybernetics, 90, 33–40.

- ↑ Bergus, G. R., Chapman, G. B., Levy, B. T., Ely, J. W., & Oppliger, R. A. (1998). Clinical diagnosis and order of information. Medical Decision Making, 18, 412–417.

![{\displaystyle [0;1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc3bf59a5da5d8181083b228c8933efbda133483)