La lógica del lenguaje clásico

La lógica del lenguaje clásico

Resumen

El capítulo comienza examinando la transición del lenguaje clínico tradicional al lenguaje de máquina encriptado en el contexto de la medicina. Se enfatiza la importancia del tiempo como portador de información e introduce la idea de utilizar el lenguaje de máquina para comprender mejor los síntomas médicos.

Se reconoce la validez del lenguaje clínico tradicional arraigado en la realidad clínica y demostrado como autoritario en el diagnóstico. Sin embargo, se destaca la oportunidad de validar la ciencia médica diagnóstica a través de un enfoque de lenguaje y sistema de máquina.

Luego, se examina el campo de la biología craneofacial, citando un estudio de Townsend y Brook que plantea preguntas fundamentales en la investigación craneofacial. Se discute la importancia de un enfoque interdisciplinario y los avances tecnológicos en el campo, incluida la secuenciación del genoma y la imagenología diagnóstica avanzada.

Se destaca el papel de la epigenética y la fenómica en la determinación de las variaciones en la forma y función craneofacial, haciendo referencia a varios estudios y autores que profundizan en este tema.

A continuación, se aborda un caso clínico que involucra a un paciente con dolor orofacial, examinando cómo se aplica el lenguaje lógico clásico para formular un diagnóstico y tratamiento utilizando predicados e inferencias lógicas.

Se analizan datos instrumentales y clínicos relacionados con el caso, destacando el uso de reglas lógicas para confirmar o refutar hipótesis diagnósticas.

Finalmente, se plantea la necesidad de un lenguaje lógico más flexible, adaptable a las sutilezas de la práctica clínica. Se enfatiza la importancia de mantenerse abierto a la evolución de la investigación y el conocimiento médico. Se discute la posibilidad de que nuevos descubrimientos puedan desafiar creencias actuales y requerir una adaptación del lenguaje lógico utilizado en la medicina.

Introducción

Nos separamos en el capítulo anterior sobre la 'Lógica del lenguaje médico' en un intento de desviar la atención del síntoma o signo clínico al lenguaje de máquina encriptado para lo cual, los argumentos de Donald E Stanley, Daniel G Campos y Pat Croskerry son bienvenidos pero conectado al tiempo como portador de información (anticipación del síntoma) y al mensaje como lenguaje de máquina y no como lenguaje no verbal).[1][2]

Evidentemente, esto no excluye la validez de la historia clínica construida sobre un lenguaje verbal pseudoformal ya bien arraigado en la realidad clínica y que ya ha demostrado su autoridad diagnóstica. El intento de cambiar la atención a un lenguaje de máquina y al Sistema no ofrece más que una oportunidad para la validación de la Ciencia Médica de Diagnóstico.

Definitivamente somos conscientes de que nuestro Linux Sapiens todavía está perplejo sobre lo que se ha anticipado y continúa preguntándose

«... pero... ¿Podría la lógica del lenguaje clásico ayudarnos a resolver el dilema de la pobre Mary Poppins?»

(un poco de paciencia por favor) |

No podemos dar una respuesta convencional porque la ciencia no avanza con afirmaciones que no estén justificadas por preguntas y reflexiones validadas científicamente; y esta es precisamente la razón por la que intentaremos dar voz a algunos pensamientos, perplejidades y dudas expresadas sobre algunos temas básicos puestos en discusión en algunos artículos científicos.

Uno de estos temas fundamentales es la 'Biología Craneofacial'.

Comencemos con un conocido estudio de Townsend y Brook[3]: en este trabajo, los autores cuestionan el status quo de la investigación fundamental y aplicada en 'biología craneofacial' para extraer consideraciones e implicaciones clínicas. Uno de los temas que cubrieron fue el "Enfoque interdisciplinario", en el que Geoffrey Sperber y su hijo Steven vieron la fuerza del progreso exponencial de la 'Biología craneofacial' en innovaciones tecnológicas como la secuenciación de genes, la tomografía computarizada, la resonancia magnética, el escaneo láser, el análisis de imágenes. , ultrasonografía y espectroscopia[4].

Otro tema de gran interés para la implementación de la 'Biología Craneofacial' es la conciencia de que los sistemas biológicos son 'Sistemas Complejos'[5] y que la 'Epigenética' juega un papel clave en la biología molecular craneofacial. Investigadores de Adelaide y Sydney aportan una revisión crítica en el campo de la epigenética dirigida, de hecho, a las disciplinas dental y craneofacial.[6] La fenómica, en particular, discutida por estos autores (ver Fenómica)) es un campo de investigación general que implica la medición de los cambios en los dientes y las estructuras orofaciales asociadas que resultan de las interacciones entre factores genéticos, epigenéticos y ambientales durante el desarrollo..[7]En este mismo contexto, cabe destacar el trabajo de Irma Thesleff desde Helsinki, Finlandia. Ella explica en su trabajo que hay una serie de centros de señalización transitorios en el epitelio dental que juegan un papel importante en el programa de desarrollo de los dientes..[8] Además, hay otros trabajos, de Peterkova R, Hovor akova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, que brindan una revisión fascinante de los procesos que ocurren durante el desarrollo dental.;[9][10][11] en aras de la exhaustividad, no olvidemos los trabajos de Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S y Bartold PM., quienes revisan documentación completa sobre células madre, ingeniería de tejidos y regeneración periodontal..[12]

En esta revisión no podían faltar argumentos sobre las influencias genéticas, epigenéticas y ambientales durante la morfogénesis que conducen a variaciones en el número, tamaño y forma del diente.[13][14] y la influencia de la presión de la lengua sobre el crecimiento y la función craneofacial.[15][16]El extraordinario trabajo de Townsend y Brook también merece una mención.[3],y el contenido intrínseco de lo que se ha informado en él coincide igualmente bien con otro autor encomiable: HC Slavkin.[17] Slavkin afirma que:

- "El futuro está lleno de oportunidades significativas para mejorar los resultados clínicos de las malformaciones craneofaciales congénitas y adquiridas. Los médicos desempeñan un papel clave, ya que el pensamiento crítico y la audiencia clínica mejoran sustancialmente la precisión del diagnóstico y, por lo tanto, los resultados de salud clínica".

«... Entiendo el progreso de la Ciencia descrito por los autores pero no entiendo el cambio de pensamiento»

(te doy un ejemplo practico) |

En el capítulo “Introducción” planteamos ciertas cuestiones sobre el tema de la maloclusión pero en este contexto simulamos la lógica del lenguaje médico del odontólogo ante el caso clínico presentado en el “Capítulo Introducción” con sus conclusiones diagnósticas y terapéuticas.

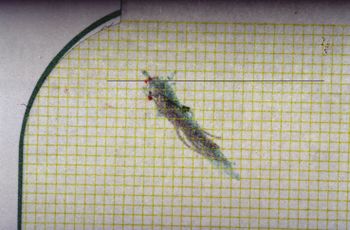

El paciente tiene una mordida cruzada unilateral posterior y una mordida abierta anterior.[18] La mordida cruzada es otro elemento perturbador de la oclusión normal.[19] por lo que es obligatorio tratarlo junto con la mordida abierta.[20][21] Este tipo de razonamiento significa que el modelo (sistema masticatorio) está 'normalizado a la oclusión'; y leído al revés, significa que la discrepancia oclusal es la causa de la maloclusión, por lo tanto, una enfermedad del Sistema Masticatorio, y por lo tanto, se justifica una intervención para restaurar la función masticatoria fisiológica. (Figura 1a).

Este ejemplo es Lenguaje Lógico Clásico, como vamos a explicar en detalle, pero ahora surge una duda:

- En el momento en que los axiomas de ortodoncia y ortognática estaban construyendo protocolos confirmados por la Comunidad Científica Internacional, ¿estaban al tanto de la información que discutimos en la introducción de este capítulo?

(claro, pero la secuencia lógica ya ha sido anticipada)

Si el mismo caso fuera interpretado con una mentalidad que siguiera una 'lógica del lenguaje del sistema' (se discutirá en el capítulo correspondiente), las conclusiones serían sorprendentes.

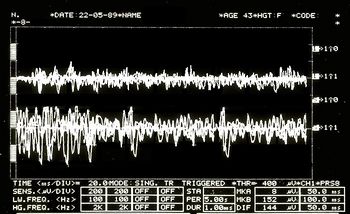

Si observamos las respuestas electrofisiológicas realizadas en el paciente con maloclusión en las figuras 1b, 1c y 1d (con la explicación hecha directamente en la leyenda para simplificar la discusión), notaremos que estos datos pueden hacernos pensar en cualquier cosa menos en una 'Maloclusión'. ' y, por tanto, los axiomas de tipo ortodóncico y ortognático 'causa/efecto' dejan un vacío conceptual.«Déjame entender mejor qué tiene que ver la lógica del lenguaje clásico con esto.»

(Lo haremos siguiendo el caso clínico de nuestra Mary Poppins) |

Formalismo matemático

En este capítulo, retomaremos el caso clínico de la desafortunada Mary Poppins que sufría de Dolor Orofacial desde hace más de 10 años a la cual su dentista le diagnosticó un 'Trastorno Temporomandibular' (TMDs) o mejor dicho Dolor Orofacial por TTMs. Para comprender mejor por qué la formulación diagnóstica exacta sigue siendo compleja con una Lógica del lenguaje clásico, debemos comprender el concepto en el que se basa la filosofía del lenguaje clásico con una breve introducción al tema.

Proposiciones

La lógica clásica se basa en proposiciones. A menudo se dice que una proposición es una oración que pregunta si la proposición es verdadera o falsa. De hecho, una proposición en matemáticas suele ser verdadera o falsa, pero obviamente esto es un poco demasiado vago para ser una definición. Puede tomarse, en el mejor de los casos, como una advertencia: si una oración, expresada en lenguaje común, no tiene sentido preguntar si es verdadera o falsa, no será una proposición sino otra cosa.

Se puede argumentar si las oraciones del lenguaje común son proposiciones o no, ya que en muchos casos no suele ser evidente si una determinada declaración es verdadera o falsa.

Afortunadamente, las proposiciones matemáticas, si están bien expresadas, no presentan tales ambigüedades”.

Las proposiciones más simples se pueden combinar entre sí para formar proposiciones nuevas y más complejas. Esto ocurre con la ayuda de operadores llamados operadores lógicos y conectores cuantificadores que se pueden reducir a los siguientes[22]:

- Conjunción, que se indica con el símbolo (y):

- Disyunción, que se indica con el símbolo (o):

- La negación, que se indica con el símbolo (no):

- Implicación, que se indica con el símbolo(si... entonces):

- Consecuencia, que se indica con el símbolo (es una partición de..):

- Cuantificador universal, que se indica con el símbolo (para todos):

- Demostración, que se indica con el símbolo (tal que): y

- Membresía, que se indica con el símbolo (es un elemento de) o por el símbolo (no es un elemento de):

Demostración por absurdo

Además, en la lógica clásica existe un principio llamado tercero excluido que declara que una oración que no puede ser falsa debe tomarse como verdadera ya que no existe una tercera posibilidad.

Supongamos que necesitamos probar que la proposición es verdad. El procedimiento consiste en demostrar que el supuesto de que es falsa conduce a una contradicción lógica. Así la proposición no puede ser falso, y por tanto, según la ley del tercero excluido, debe ser verdadero. Este método de demostración se llama demostración por absurdo.[23]

Predicados

Lo que hemos descrito brevemente hasta ahora es la lógica de las proposiciones. Una proposición afirma algo sobre objetos matemáticos específicos como: '2 es mayor que 1, por lo que 1 es menor que 2' o 'un cuadrado no tiene 5 lados, entonces un cuadrado no es un pentágono'. Muchas veces, sin embargo, los enunciados matemáticos no se refieren al objeto único, sino a objetos genéricos de un conjunto como: ' son más altos que 2 metros donde denota un grupo genérico (por ejemplo, todos los jugadores de voleibol). En este caso hablamos de predicados..

Intuitivamente, un predicado es una oración que se refiere a un grupo de elementos (que en nuestro caso médico serán los pacientes) y que afirma algo sobre ellos.«Entonces la pobre Mary Poppins es una paciente de TMD o no lo es!»

(veamos que nos dice la lógica del lenguaje clásico) |

2nd Clinical Approach

(Hover over the images)

Dental propositions

While seeking to use the mathematical formalism to translate the conclusions reached by the dentist with classical logic language, we consider the following predicates:

- x Normal patients (normal stands for patients commonly present in the specialist setting)

- Bone remodelling with osteophyte from stratigraphic examination and condylar CT; and

- Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) resulting in Orofacial Pain (OP)

- Specific patient: Mary Poppins

Any normal patient who is positive on the radiographic examination of the TMJ [Figure 2 and 3] is affected by TMDs ; from this it follows that being Mary Poppins positive (and also being a "Normal" patient) on the TMJ x-ray then Mary Poppins is also affected by TMDs The language of predicates is expressed in the following way:

.

At this point, it must also be considered that predicate logic is not used only to prove that a particular set of premises imply a particular evidence . It is also used to prove that a particular assertion is not true, or that a particular piece of knowledge is logically compatible/incompatible with a particular evidence.

In order to prove that this proposition is true we must use the above mentioneddemonstration by absurdity. If its denial creates a contradiction, surely the dentist's proposition will be true:

.

"" states that it is not true that those who test positive on TMJ CT have TMDs, so Mary Poppins (TMJ CT positive normal patient) does not have TMDs.

The dentist believes that Mary Poppins' claim (that she does not have TMD under these premises) is a contradiction so the main claim is true.

Neurophysiological proposition

Let us imagine that the neurologist disagrees with the conclusion and asserts that Mary Poppins is not affected by TMDs or that at least it is not the main cause of Orofacial Pain, but that, rather, she is affected by a neuromotor Orofacial Pain (nOP), therefore that she does not belong to the group of 'normal patients' but is to be considered a 'non-specific patient' (uncommon in the specialist context).

Obviously, this dialectic would last indefinitely because both would defend their scientific-clinical context; but let us see what happens in the logic of predicates.

The neurologist's statement would be like:

.

"" means that every patient who is TMJ CT positive has TMDs but even though Mary Poppins is TMJ CT positive, she does not have TMDs.

In order to prove that this proposition is true, we must use once again the above mentioned demonstration by absurdity. If its denial creates a contradiction, surely the neurologist's proposition will be true:

.

Following the logical rules of predicates, there is no reason to say that denial (4) is contradictory or meaningless, therefore the neurologist (unlike the dentist) would not seem to have the logical tools to confirm his conclusion.«then the dentist triumphs!»

(don't take it for granted) |

Compatibility and incompatibility of the statements

The complication lies in the fact that the dentist will present a series of statements as clinical reports such as the stratigraphy and CT of the TMJ, that indicate an anatomical flattening of the joint, axiography of the condylar traces with a reduction in kinematic convexity and a tracing EMG interference pattern in which an asymmetrical pattern on the masseters is highlighted. These assertions can easily be considered a contributing cause of the damage to the Temporomandibular Joint and, therefore, responsible for the 'Orofacial pain'.

Documents, reports and clinical evidence can be used to make the neurologist's assertion incompatible and the dentist's diagnostic conclusion compatible. To do this we must present some logical rules that describe the compatibility or incompatibility of the logic of classical language:

- A set of sentences , and a number of other phrases or statements are logically compatible if, and only if, the union between them is coherent.

- A set of sentences , and a number of other phrases or statements are logically incompatible if, and only if, the union between them is incoherent.

Let us try to follow this reasoning with practical examples:

The dentist colleague exposes the following sentence:

: Following the personalized techniques suggested by Xin Liang et al.[28] who focuses on the quantitative microstructural analysis of the fraction of the bone value, the trabecular number, the trabecular thickness and the trabecular separation on each slice of the CT scan of a TMJ, it appears that Mary Poppins is affected by Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) and the consequence causes Orofacial Pain.

At this point, however, the thesis must be confirmed with further clinical and laboratory tests, and in fact the colleague produces a series of assertions that should pass the compatibility filter as described above, namely:

Bone remodelling: The flattening of the axiographic traces highlighted in figure 5 indicates the joint remodelling of the right TMJ of Mary Poppins, such a report can be correlated to a series of researches and articles that confirm how malocclusion can be associated with morphological changes in the temporomandibular joints, particularly when combined with the age as the presence of a chronic malocclusion can worsen the picture of bone remodelling.[29] These scientific references determine the compatibility of the assertion.

Sensitivity and specificity of the axiographic measurement: A study was conducted to verify the sensitivity and specificity of the data collected from a group of patients affected by temporomandibular joint disorders with an ARCUSdigma axiographic system[30]; it confirmed a sensitivity of the 84.21% and a 92.86% sensitivity for the right and left TMJs respectively, and a specificity of 93.75% and 95.65%.[31] These scientific references determine compatibility of the assertion in the dental context precisely because of the consistency of related studies.[32]

Alteration of condylar paths: Urbano Santana-Mora and coll.[33] evaluated 24 adult patients suffering from severe chronic unilateral pain diagnosed as Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs). The following functional and dynamic factors were evaluated:

masticatory function;

remodelling of the TMJ or condylar pathway (CP); and lateral movement of the jaw or lateral guide (LG).

The CPs were assessed using conventional axiography and LG was assessed by using kinesiograph tracing[34]; Seventeen (71%) of the 24 (100%) patients consistently showed a side of habitual chewing side. The mean and standard deviation of the CP angles was 47.90 9.24) degrees. The average of LG angles was 42.9511.78 degrees.

Data collection emerged from the conception of a new TMD paradigm in which the affected side could be the usual chewing side, the side where the mandibular lateral kinematic angle was flatter. This parameter may also be compatible with the dental claim.

EMG Intereference pattern: M.O. Mazzetto and coll.[35] showed that the electromyographic activity of the anterior temporal muscles and the masseter was positively correlated with the "Craniomandibular index", indiced (CMI) with a and suggesting that the use of CMI to quantify the severity of TMDs and EMG to assess the masticatory muscle function, may be an important diagnostic and therapeutic elements. These scientific references determine compatibility of the assertion.

?

Obviously, the dentist colleague could endlessly keep on casting his statements, indefinitely.

Well, all of these statements seem coherent with the sentence initially described, whereby the dentist colleague feels justified in saying that the set of sentences , and a number of other assertions or clinical data are logically compatible as the union between them is coherent.«Following the logic of classical language, the dentist is right!»

(It would seem so! But, be careful, only in his own dental context!) |

This statement is so true that the could be infinitely extended, widened enough to obtain an that corresponds to it in an infinite significance, as long as it remains limited in its context; yet, without meaning anything from a clinical point of view in other contexts, like in the neurologist one, for instance.

Final considerations

From a perspective of observation of this kind, the Logic of Predicates can only fortify the dentist’s reasoning and, at the same time, strengthen the principle of the excluded third: the principle is strengthened through the compatibility of the additional assertions which grant the dentist a complete coherence in the diagnosis and in confirming the sentence : Poor Mary Poppins either has TMD, or she has not.«...and what if, with the advancement of research, new phenomena were discovered that would prove the neurologist right, instead of the dentist?»

|

Basically, given the compatibility of the assertions , coherently saying that Orofacial Pain is caused by a Temporomandibular Disorders could become incompatible if another series of assertions were shown to be coherent: this would make a different sentence compatible : could poor Mary Poppins suffer from Orofacial Pain from a neuromotor disorder (nOP) and not by a Temporomandibular Disorders?

In the current medical language logic, such assertions only remain assertions, because the convictions and opinions do not allow a consequent and quick change of the mindset.

Moreover, taking into account the risk that this change entails, in fact, we might consider a recent article on the epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders[36] in which the authors confirm that despite the methodological and population differences, pain in the temporomandibular region appears to be relatively common, occurring in about the 10% of the population; we may then objectively be led to hypothesize that our Mary Poppins can be included in the 10% of the patients mentioned in the epidemiological study, and contextually be classified as a patient suffering from Orofacial Pain from Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs).

In conclusion, it is evident that a classical logic of language, which has an extremely dichotomous approach (either it is white or it is black), cannot depict the many shades that occur in real clinical situations.

We need to find a more convenient and suitable language logic...«... can we then think of a Probabilistic Language Logic?»

(perhaps) |

- ↑ Stanley DE, Campos DG, «The logic of medical diagnosis», in Perspect Biol Med, 2013».

PMID:23974509

DOI:10.1353/pbm.2013.0019 - ↑ Croskerry P, «Adaptive expertise in medical decision making», in Med Teach, 2018».

PMID:30033794

DOI:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1484898 - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Townsend GC, Brook AH, «The face, the future, and dental practice: how research in craniofacial biology will influence patient care», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24646132

DOI:10.1111/adj.12157 - ↑ Sperber GH, Sperber SM, «The genesis of craniofacial biology as a health science discipline», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24495071

DOI:10.1111/adj.12131 - ↑ Brook AH, Brook O'Donnell M, Hone A, Hart E, Hughes TE, Smith RN, Townsend GC, «General and craniofacial development are complex adaptive processes influenced by diversity», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24617813

DOI:10.1111/adj.12158 - ↑ Williams SD, Hughes TE, Adler CJ, Brook AH, Townsend GC, «Epigenetics: a new frontier in dentistry», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24611746

DOI:10.1111/adj.12155 - ↑ Yong R, Ranjitkar S, Townsend GC, Brook AH, Smith RN, Evans AR, Hughes TE, Lekkas D, «Dental phenomics: advancing genotype to phenotype correlations in craniofacial research», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24611797

DOI:10.1111/adj.12156 - ↑ Thesleff I, «Current understanding of the process of tooth formation: transfer from the laboratory to the clinic», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12102 - ↑ Peterkova R, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, «Three‐dimensional analysis of the early development of the dentition», in Aust Dent J, Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd on behalf of Australian Dental Association, 2014».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12130 - ↑ Lesot H, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Peterkova R, «Three‐dimensional analysis of molar development in the mouse from the cap to bell stage», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12132 - ↑ Hughes TE, Townsend GC, Pinkerton SK, Bockmann MR, Seow WK, Brook AH, Richards LC, Mihailidis S, Ranjitkar S, Lekkas D, «The teeth and faces of twins: providing insights into dentofacial development and oral health for practising oral health professionals», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12101 - ↑ Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, «Stem cells, tissue engineering and periodontal regeneration», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12100 - ↑ {{Cite book | autore = Brook AH | autore2 = Jernvall J | autore3 = Smith RN | autore4 = Hughes TE | autore5 = Townsend GC | titolo = The Dentition: The Outcomes of Morphogenesis Leading to Variations of Tooth Number, Size and Shape | url = https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/adj.12160 | volume = | opera = Aust Dent J | anno = 2014 | editore = | città = | ISBN = | PMID = | PMCID = | DOI = 10.1111/adj.12160 | oaf = | LCCN = | OCLC =

- ↑ Seow WK, «Developmental defects of enamel and dentine: challenges for basic science research and clinical management», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

PMID:24164394

DOI:10.1111/adj.12104 - ↑ Kieser JA, Farland MG, Jack H, Farella M, Wang Y, Rohrle O, «The role of oral soft tissues in swallowing function: what can tongue pressure tell us?», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12103 - ↑ Slavkin HC, «Research on Craniofacial Genetics and Developmental Biology: Implications for the Future of Academic Dentistry», in J Dent Educ, 1983».

PMID:6573384 - ↑ Slavkin HC, «The Future of Research in Craniofacial Biology and What This Will Mean for Oral Health Professional Education and Clinical Practice», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

PMID:24433547

DOI:10.1111/adj.12105 - ↑

Littlewood SJ, Kandasamy S, Huang G, «Retention and relapse in clinical practice», in Aust Dent J, 2017».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12475 - ↑ Miamoto CB, Silva Marques L, Abreu LG, Paiva SM, «Impact of two early treatment protocols for anterior dental crossbite on children’s quality of life», in Dental Press J Orthod, 2018».

- ↑ Alachioti XS, Dimopoulou E, Vlasakidou A, Athanasiou AE, «Amelogenesis imperfecta and anterior open bite: Etiological, classification, clinical and management interrelationships», in J Orthod Sci, 2014».

DOI:10.4103/2278-0203.127547 - ↑ Mizrahi E, «A review of anterior open bite», in Br J Orthod, 1978».

PMID:284793

DOI:10.1179/bjo.5.1.21 - ↑ For the sake of simplicity of exposition and reading, we will deal in this chapter with the symbol of belonging, the symbol of consequence and the "such that" as if they were quantifiers and connectives of propositions in classical logic.

Strictly speaking, within classical logic they should not be treated as such, but even if we do, this does not absolutely change the meaning of the speech and no inconsistencies of any kind are created. - ↑ Pereira LM, Pinto AM, «Reductio ad Absurdum Argumentation in Normal Logic Programs», Arg NMR, 2007, Tempe, Arizona - Caparica, Portugal – in «Argumentation and Non-Monotonic Reasoning - An LPNMR Workshop».

- ↑ Castroflorio T, Talpone F, Deregibus A, Piancino MG, Bracco P, «Effects of a Functional Appliance on Masticatory Muscles of Young Adults Suffering From Muscle-Related Temporomandibular Disorder», in J Oral Rehabil, 2004».

PMID:15189308

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01274.x - ↑ Maeda N, Kodama N, Manda Y, Kawakami S, Oki K, Minagi S, «Characteristics of Grouped Discharge Waveforms Observed in Long-term Masseter Muscle Electromyographic Recording: A Preliminary Study», in Acta Med Okayama, Okayama University Medical School, 2019, Okayama, Japan».

PMID:31439959

DOI:10.18926/AMO/56938 - ↑ Rudy TE, «Psychophysiological Assessment in Chronic Orofacial Pain», in Anesth Prog, American Dental Society of Anesthesiology, 1990».

ISSN: 0003-3006/90

PMID:2085203 - PMCID:PMC2190318 - ↑ Woźniak K, Piątkowska D, Lipski M, Mehr K, «Surface electromyography in orthodontics - a literature review», in Med Sci Monit, 2013».

e-ISSN: 1643-3750

PMID:23722255 - PMCID:PMC3673808

DOI:10.12659/MSM.883927 - ↑ Liang X, Liu S, Qu X, Wang Z, Zheng J, Xie X, Ma G, Zhang Z, Ma X, «Evaluation of Trabecular Structure Changes in Osteoarthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint With Cone Beam Computed Tomography Imaging», in Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2017».

PMID:28732700

DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2017.05.514 - ↑ Solberg WK, Bibb CA, Nordström BB, Hansson TL, «Malocclusion Associated With Temporomandibular Joint Changes in Young Adults at Autopsy», in Am J Orthod, 1986».

PMID:3457531

DOI:10.1016/0002-9416(86)90055-2 - ↑ KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach / Ris

- ↑ Kobs G, Didziulyte A, Kirlys R, Stacevicius M, «Reliability of ARCUSdigma (KaVo) in Diagnosing Temporomandibular Joint Pathology», in Stomatologija, 2007».

PMID:17637527 - ↑ Piancino MG, Roberi L, Frongia G, Reverdito M, Slavicek R, Bracco P, «Computerized axiography in TMD patients before and after therapy with 'function generating bites'», in J Oral Rehabil, 2008».

PMID:18197841

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01815.x - ↑ López-Cedrún J, Santana-Mora U, Pombo M, Pérez Del Palomar A, Alonso De la Peña V, Mora MJ, Santana U, «Jaw Biodynamic Data for 24 Patients With Chronic Unilateral Temporomandibular Disorder», in Sci Data, 2017».

PMID:29112190 - PMCID:PMC5674825

DOI:10.1038/sdata.2017.168

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Myotronics Inc., Kent, WA, US

- ↑ Oliveira Mazzetto M, Almeida Rodrigues C, Valencise Magri L, Oliveira Melchior M, Paiva G, «Severity of TMD Related to Age, Sex and Electromyographic Analysis», in Braz Dent J, 2014».

DOI:10.1590/0103-6440201302310 - ↑ LeResche L, «Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors», in Crit Rev Oral Biol Med, 1997».

PMID:9260045

DOI:10.1177/10454411970080030401

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system