'The logic of the probabilistic language'

'The logic of the probabilistic language'

Abstract

The text deals with the logic of probabilistic language applied to the medical field, highlighting how uncertainty is an intrinsic part of scientific practice. Through probabilistic and statistical concepts, efforts are made to manage and understand the uncertainties associated with medical theory and practice.

The role of probability in the relationship between theory and observation is emphasized, distinguishing between subjective uncertainty and randomness. Subjective uncertainty concerns individuals' state of knowledge and belief, while randomness refers to the lack of a certain connection between cause and effect.

In the medical approach, the importance of understanding and distinguishing between subjective and objective probability is discussed. Subjective probability reflects individual belief, while objective probability is based on data and empirical evidence.

The concept of probabilistic-causal analysis is then further explored, which seeks to quantify the relationship between events and random processes in clinical diagnosis. A detailed exposition is presented on how conditional probabilities can be interpreted and how causal relevance partitioning can be used to formulate a differential diagnosis.

Finally, the theme of interdisciplinarity in scientific research is addressed, highlighting the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to tackling complex problems. Fuzzy logic is also mentioned as a possible tool for managing uncertainty in medical contexts.

Every scientific idea—whether in medicine, architecture, engineering, chemistry, or any other field—when implemented, is prone to small errors and uncertainties. Mathematics, through the lens of probability theory and statistical inference, aids in precisely managing and thereby mitigating these uncertainties. It must always be considered that in all practical scenarios, "the outcomes also depend on many other external factors to the theory," be they initial and environmental conditions, experimental errors, or others.

The uncertainties surrounding these factors render the theory-observation relationship probabilistic. In medical practice, two types of uncertainty predominantly impact diagnoses: subjective uncertainty and causality.[1][2] Therefore, in this context, it becomes crucial to differentiate between these two uncertainties and to demonstrate that the concept of probability assumes different meanings in these contexts. We will endeavor to elucidate these concepts by connecting each critical step to the clinical approach that has been documented in previous chapters, particularly focusing on the dental and neurological domains in vying for diagnostic supremacy for our dear Mary Poppins.

Subjective Uncertainty and Causality

Let's imagine asking Mary Poppins which of the two medical colleagues—the dentist or the neurologist—is correct.

The question would generate a kind of agitation based on internal uncertainty; therefore, the notions of certainty and uncertainty refer to the subjective epistemic states of human beings, and not to states of the external world, because there is no certainty or uncertainty in that world. In this sense, as we have mentioned, there are an inner world and an external world that both do not adhere to canons of uncertainty, but rather to probability.

Mary Poppins may be subjectively certain or uncertain as to whether she is suffering from TMDs or a neuropathic or neuromuscular form of OP. This is because "uncertainty" is a subjective, epistemic state below the threshold of knowledge and belief; hence the term.

Subjective Uncertainty

Without a doubt, the term ‘subjective’ alarms many, especially those who aim to practice science by pursuing the noble ideal of ‘objectivity,’ as this term is perceived by common sense. Therefore, it is appropriate to make some clarifications on the use of this term in this context:

‘Subjective’ indicates that the probability assessment depends on the information status of the individual who performs it.

‘Objective’ does not mean arbitrary.

The so-called ‘objectivity,’ as perceived by those outside scientific research, is achieved when a community of rational beings shares the same state of information. But even in this case, one should more properly speak of ‘intersubjectivity’ (i.e., the sharing of subjective opinions by a group).

In clinical cases—precisely because patients rarely possess advanced notions of medicine—subjective uncertainty must be considered. Living with uncertainty requires us to adopt a probabilistic approach.

Causality

Causality indicates the lack of a certain connection between cause and effect. The uncertainty of a close union between the source and the phenomenon is among the most challenging problems in determining a diagnosis.

In a clinical case, a phenomenon Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A(x)} (such as a malocclusion, a crossbite, an openbite, etc.) is randomly associated with another phenomenon Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle B(x)} (such as TMJ bone degeneration); when there are exceptions for which the logical proposition Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A(x) \rightarrow B(x)} is not always true (but it is most of the time), we will say that the relation Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A(x) \rightarrow B(x)} is not always true but it is probable.

Subjective and Objective Probability

In this chapter, we revisit some topics previously discussed in the insightful book by Kazem Sadegh-Zadeh[3], which tackles the problem of the logic of medical language. We adapt their content to our clinical case of Mary Poppins, aiming to keep our understanding more relevant to dental contexts.

Events that are both random and subjectively uncertain are considered probable; therefore, causality and uncertainty are approached as qualitative, comparative, or quantitative probabilities.

To clarify this concept, let's use the example of Mary Poppins. A doctor, after hearing her symptoms, could state that:

- Mary Poppins is probably suffering from TMDs (qualitative term).

- Mary Poppins is more likely to have TMDs than neuropathic OP (comparative term: the number of diagnosed cases of TMDs vs. neuropathic OP).

- The probability that Mary Poppins has TMDs is 0.15 (quantitative term, relative to the population).

Subjective Probability

In contexts of human subjective uncertainty, probabilistic, qualitative, comparative, and/or quantitative data can be interpreted by clinicians as measures of subjective uncertainty, to make 'states of conviction' numerically representable.

For instance, stating "the probability that Mary Poppins is affected by TMDs is 0.15 of the cases" is akin to saying "with a 15% degree of belief, I think that Mary Poppins is affected by TMDs"; indicating that the degree of conviction corresponds to the degree of subjective probability.

Objective Probability

Conversely, events and random processes cannot be accurately described by deterministic processes in the form 'if A then B'. Statistics are utilized to quantify the frequency of the association between A and B, representing their relationship as a degree of probability, which introduces the concept of objective probability.

Amid the increasing acknowledgment of the role of probabilization of uncertainty and randomness in medicine since the eighteenth century, the term "probability" has become an integral part of medical language, methodology, and epistemology. Unfortunately, the distinction between subjective and objective probability is not always clearly made in medicine, as is the case in other disciplines too. Nevertheless, the vital contribution of probability theory in medicine, especially in concepts of probability in etiology, epidemiology, diagnostics, and therapy, lies in its aid in understanding and representing biological causality.

Probabilistic-Causal Analysis

From these premises, it is evident that clinical diagnosis employs the so-called hypothetical-deductive method, known as DN[4] (deductive-nomological model[5]). However, this is not realistic, as the medical knowledge used in clinical decision-making rarely contains causal deterministic laws that allow for causal explanations and, consequently, the formulation of clinical diagnoses, among other things in the specialist context. Let us re-examine the case of Mary Poppins, this time adopting a probabilistic-causal approach.

Consider a number Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} of individuals, including those who report Orofacial Pain, who generally have bone degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint. However, there might also be other apparently unrelated causes. We must mathematically translate the 'relevance' of these causal uncertainties in determining a diagnosis.

The casual relevance

To do this we consider the degree of causal relevance Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (cr)} of an event Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle E_1} with respect to an event Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle E_2} where:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle E_1} = patients with bone degeneration of the temporomandibular joint.

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle E_2} = patients reporting orofacial pain.

- = patients without bone degeneration of the temporomandibular joint.

We will use the conditional probability Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(A \mid B)} , that is the probability that the Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A} event occurs only after the event Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle B} has already occurred.

With these premises the causal relevance Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr} of the sample Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} of patients is:

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr=P(E_2 \mid E_1)- P(E_2 \mid E_3)}

where

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(E_2 \mid E_1)} indicates the probability that some people (among Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} taken into consideration) suffer from Orofacial Pain caused by bone degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint,

while

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(E_2 \mid E_3)} indicates the probability that other people (always among Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} taken into consideration) suffer from Orofacial Pain conditioned by something other than bone degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint.

Since all probability suggest that Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(A \mid B)} is a value between Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 0 } and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 1 } , the parameter Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (cr)} will be a number that is between Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle -1 } and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 1 } .

The meanings that we can give to this number are as follows:

- we have the extreme cases (which in reality never occur) which are:

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr=1} indicating that the only cause of orofacial pain is bone degeneration of the TMJ,

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr=-1} which indicates that the cause of orofacial pain is never bone degeneration of the TMJ but is something else,

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr=0} indicating that the probability that orofacial pain is caused by bone degeneration of the TMJ or otherwise is exactly the same,

- and the intermediate cases (which are the realistic ones)

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr>0} indicating that the cause of orofacial pain is more likely to be bone degeneration of the TMJ,

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle cr<0} which indicates that the cause of orofacial pain is more likely not bone degeneration of the TMJ.

Second Clinical Approach

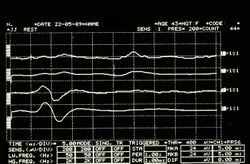

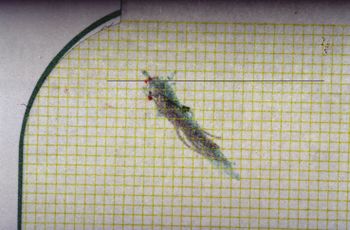

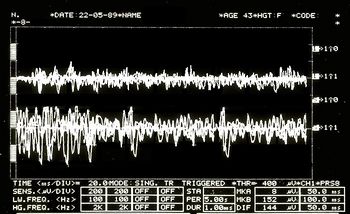

(hover over the images)

So be it then Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D)} the probability of finding, in the sample of our Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} people, individuals who present the elements belonging to the aforementioned set Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,\delta_2,...,\delta_n\}}

In order to take advantage of the information provided by this dataset, the concept of partition of causal relevance is introduced:

The partition of causal relevance

- Always be Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} the number of people we have to conduct the analyses upon, if we divide (based on certain conditions as explained below) this group into Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle k} subsets Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_i} with Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle i=1,2,\dots,k} , a cluster is created that is called a "partition set" Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \pi} :

- Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \pi = \{C_1, C_2,\dots,C_k \} \qquad \qquad \text{with} \qquad \qquad C_i \subset n , }

where with the symbolism Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_i \subset n } it indicates that the subclass Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_i} is contained in Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} .

The partition Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \pi} , in order for it to be defined as a partition of causal relevance, must have these properties:

- For each subclass Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_i} the condition must apply Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle rc=P(D \mid C_i)- P(D )\neq 0, } ie the probability of finding in the subgroup Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_i} a person who has the symptoms, clinical signs and elements belonging to the set Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,\delta_2,...,\delta_n\}} . A causally relevant partition of this type is said to be homogeneous.

- Each subset Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_i} must be 'elementary', i.e. it must not be further divided into other subsets, because if these existed they would have no causal relevance.

Now let us assume, for example, that the population sample Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} , to which our good patient Mary Poppins belongs, is a category of subjects aged 20 to 70. We also assume that in this population we have those who present the elements belonging to the data set Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,.....\delta_n\}} which correspond to the laboratory tests mentioned above and precisa in 'The logic of classical language'.

Let us suppose that in a sample of 10,000 subjects from 20 to 70 we will have an incidence of 30 subjects Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p(D)=0.003} showing clinical signs Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \delta_1} and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \delta_4 } . We preferred to use these reports for the demonstration of the probabilistic process because in the literature the data regarding clinical signs and symptoms for Temporomandibular Disorders have too wide a variation as well as too high an incidence in our opinion.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

An example of a partition with presumed probability in which TMJ degeneration (Deg.TMJ) occurs in conjunction with Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) would be the following:

| Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D| Deg.TMJ \cap TMDs)=0.95 \qquad \qquad \; } | where | Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \C_1 \equiv Deg.TMJ \cap TMDs} | |||

| Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D| Deg.TMJ \cap noTMDs)=0.3 \qquad \qquad \quad } | where | Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_2\equiv Deg.TMJ \cap noTMDs} | |||

| Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D| no Deg.TMJ \cap TMDs)=0.199 \qquad \qquad \; } | where | Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_3\equiv no Deg.TMJ \cap TMDs} | |||

| Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D| noDeg.TMJ \cap noTMDs)=0.001 \qquad \qquad \;} | where | Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle C_4\equiv noDeg.TMJ \cap noTMDs} |

- «A homogeneous partition provides what we are used to calling Differential Diagnosis.»

Clinical situations

These conditional probabilities demonstrate that each of the partition's four subclasses is causally relevant to patient data Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,.....\delta_n\}} in the population sample Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle PO} . Given the aforementioned partition of the reference class, we have the following clinical situations:

- Mary Poppins Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \in} degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cap} Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \in} degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cap} no Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \in} no degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cap} Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \in} no degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cap} no Temporomandibular Disorders

To arrive at the final diagnosis above, we conducted a probabilistic-causal analysis of Mary Poppins' health status whose initial data were Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,.....\delta_n\}} .

In general, we can refer to a logical process in which we examine the following elements:

- an individual: Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a}

- its initial data set Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,.....\delta_n\}}

- a population sample Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n} to which it belongs,

- a base probability Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D)=0,003}

At this point we should introduce too specialized arguments that would take the reader off the topic but that have an high epistemic importance for which we will try to extract the most described logical thread of the Analysandum/Analysans concept.

The probabilistic-causal analysis of Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,.....\delta_n\}} is then a couple of the following logical forms (Analysandum / Analysans[12]):

- Analysandum Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle = \{P(D),a\}} : is a logical form that contains two parameters: probability Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle P(D)} to select a person who has the symptoms and elements belonging to the set Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=\{\delta_1,\delta_2,...,\delta_n\}} , and the generic individual Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a} who is prone to those symptoms.

- Analysan Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle = \{\pi,a,KB\}} : is a logical form that contains three parameters: the partition , the generic individual belonging to the population sample and (Knowledge Base) which includes a set of statements of conditioned probability.

For example, it can be concluded that the definitive diagnosis is the following:

- this means that our Mary Poppins is 95% affected by TMDs, since she has a degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint in addition to the positive data ..............

Strategic dental topics for authors to subscribe an article

Probabilistic Language, Medical Field, Uncertainty Management, Subjective Uncertainty, Randomness in Medicine, Objective Probability, Clinical Decision-Making, Probabilistic-Causal Analysis, Differential Diagnosis, Interdisciplinary Approach, Fuzzy Logic, Medical Diagnostics, Treatment Efficacy, Precision Medicine, Personalized Patient Care

- ↑ Vázquez-Delgado E, Cascos-Romero J, Gay-Escoda C, «Myofascial pain associated with trigger points: a literature review. Part 2: Differential diagnosis and treatment», in Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 2007».

PMID:20173729

DOI:10.4317/medoral.15.e639 - ↑ Thoppay J, Desai B, «Oral burning: local and systemic connection for a patient-centric approach», in EPMA J, 2019».

PMID:30984309 - PMCID:PMC6459460

DOI:10.1007/s13167-018-0157-3 - ↑ Sadegh-Zadeh Kazem, «Handbook of Analytic Philosophy of Medicine», Springer, 2012, Dordrecht».

ISBN: 978-94-007-2259-0

DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-2260-6 - ↑ Sarkar S, «Nagel on Reduction», in Stud Hist Philos Sci, 2015».

PMID:26386529

DOI:10.1016/j.shpsa.2015.05.006 - ↑ DN model of scientific explanation, also known as Hempel's model, Hempel–Oppenheim model, Popper–Hempel model, or covering law model

- ↑ Pantoja LLQ, De Toledo IP, Pupo YM, Porporatti AL, De Luca Canto G, Zwir LF, Guerra ENS, «Prevalence of degenerative joint disease of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review», in Clin Oral Investig, 2019».

PMID:30311063

DOI:10.1007/s00784-018-2664-y - ↑ De Toledo IP, Stefani FM, Porporatti AL, Mezzomo LA, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G, «Prevalence of otologic signs and symptoms in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis», in Clin Oral Investig, 2017».

PMID:27511214

DOI:10.1007/s00784-016-1926-9 - ↑ Bonotto D, Penteado CA, Namba EL, Cunali PA, Rached RN, Azevedo-Alanis LR, «Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in rugby players», in Gen Dent».

PMID:31355769 - ↑ da Silva CG, Pachêco-Pereira C, Porporatti AL, Savi MG, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G, «Prevalence of clinical signs of intra-articular temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis», in Am Dent Assoc, 2016». - PMCID:26552334

DOI:10.1016/j.adaj.2015.07.017 - ↑ Gauer RL, Semidey MJ, «Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders», in Am Fam Physician, 2015».

PMID:25822556 - ↑ Kohlmann T, «Epidemiology of orofacial pain», in Schmerz, 2002».

PMID:12235497

DOI:10.1007/s004820200000 - ↑ Westmeyer H, «The diagnostic process as a statistical-causal analysis», in APA, 1975».

DOI:10.1007/BF00139821

This is an Open Access resource!