Hemimastikatorischer Spasmus

Hemimastikatorischer Spasmus

Zusammenfassung

This chapter and the series of sub-chapters will be mainly dedicated to the clinical case of our poor patient Mary Poppins who had to wait 10 years to get a certain and detailed diagnosis of 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', being between two focuses that of the dental and neurological context. besides all the other branches of medicine encountered in the diagnostic path, such as dermatology which diagnosed 'Morfea'. It would be too hasty to dismiss this clinical event by confirming the diagnosis of Hemimasticatory Spasm without understanding the reason for the diagnostic delay and even less to neglect the elements that could help the clinician to formulate a diagnosis in a more rapid and detailed way. In this section of Masticationpedia, therefore, we would like to begin laying the foundations for a more formal language in medical diagnostics of the mathematical type and not the classic model in which ambiguity and vagueness can complicate the diagnostic process with sometimes dangerous decades-long delays for the life of the human being. We will therefore take up some contents already proposed in the 'Introduction' section and make them practical and clinically essential in the diagnosis of our patient Mary Poppins.

Einführung

Bevor wir uns in die Kernfrage der Diskussion über die Pathologie unserer Patientin Mary Poppins begeben, scheint es wichtig, sich auf einige Aspekte eines neuromotorischen Typs zu konzentrieren, insbesondere auf einen 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', um den Entschlüsselungsprozess des Signals zu bestimmen.

Zunächst einmal ist es nicht so komplex, eine Diagnose eines 'Hemimasticatory Spasm' zu stellen, aber es ist schwieriger, eine differenzialdiagnostische Abgrenzung zwischen einem 'Hemifacial Spasm' und der Art der Erkrankung zur Ausrichtung der Therapie vorzunehmen.

Wir sollten zunächst induzierte Bewegungsstörungen in Betracht ziehen, die als unfreiwillige oder abnormale Bewegungen definiert werden, die durch Trauma der Schädel-oder peripheren Nerven oder Wurzeln ausgelöst werden.[1] In diesem Zusammenhang sollten unfreiwillige Bewegungen einschließlich Spasmen sowie Pathologien des Zentralnervensystems sowie des peripheren Nervensystems berücksichtigt werden. In einer Studie von Seung Hwan Lee et al.[2] wurden zwei Vestibularschwannome, fünf Meningeome und zwei Epidermoidtumore einbezogen. Ein Hemifacialspasmus trat bei acht Patienten auf derselben Seite der Läsion auf, während er bei nur einem Patienten auf der gegenüberliegenden Seite der Läsion auftrat. Hinsichtlich der Pathogenese von Hemifacialspasmen waren bei sechs Patienten die Blutgefäße beteiligt, der Tumor hatte bei einem Patienten die Auskleidung des Gesichtsnervs betroffen, ein hypervaskulärer Tumor hatte den Gesichtsnerv ohne Schädigung der Blutgefäße bei einem Patienten komprimiert, und ein riesiger Tumor, der den Hirnstamm komprimierte, hatte somit die Beteiligung des kontralateralen Gesichtsnervs bei einem Patienten verursacht. Der Hemifacialspasmus löste sich bei sieben Patienten auf, während er sich bei zwei Patienten mit einem Vestibularschwannom und einem Epidermoidtumor vorübergehend verbesserte und dann nach einem Monat wieder auftrat.

Daher sollten lokale Ursachen, einschließlich zentraler Ursachen, die zu Gesichts- und/oder Kieferspasmen führen können, berücksichtigt werden, wie zum Beispiel Fälle von Vestibularschwannom und Epidermoidtumor.

Vestibuläres und Trigeminus-Schwannom

Sekundärer Hemifacialspasmus aufgrund eines Vestibularschwannoms ist sehr selten. Die Studie von S. Peker et al.[3] war der erste berichtete Fall eines Hemifacialspasmus, der auf Gamma-Knife-Radiochirurgie bei einem Patienten mit einem intrakanalikulären Vestibularschwannom ansprach. Sowohl die Spasmusauflösung als auch die Kontrolle des Tumorwachstums wurden mit einer einzigen Sitzung der Gamma-Knife-Radiochirurgie erreicht. Der 49-jährige männliche Patient hatte eine 6-monatige Anamnese mit einseitigem Hörverlust und Hemifacialspasmus. Die MRT-Untersuchung ergab ein intrakanalikuläres Vestibularschwannom. Der Patient wurde mit Radiochirurgie behandelt und erhielt 13 Gy an der 50% Isodosenlinie. Eine Kontrolle des Tumorwachstums wurde erreicht und es gab keine Veränderung des Tumorvolumens bei der letzten Nachuntersuchung nach 22 Monaten. Der Hemifacialspasmus war nach einem Jahr vollständig aufgelöst. Die chirurgische Entfernung der vermutlich verursachenden Raumforderung wurde als einzige Behandlung bei sekundärem Hemifacialspasmus beschrieben.

Die MRT ist die Bildgebungsmodalität der Wahl und ist in der geeigneten klinischen Situation in der Regel diagnostisch aussagekräftig. Die dünn geschnittenen T2-gewichteten 3D-CISS-Axialsequenzen sind wichtig für die korrekte Bewertung des zisternalen Segments des Nervs. Sie sind normalerweise hypointens in T1, hyperintens in T2 mit Kontrastmittelanreicherung nach Gadolinium. Aber es sollte uns nicht überraschen, wenn Fälle wie der von Brandon Emilio Bertot et al.[4] auftreten, in dem ein klinischer Fall eines 16-jährigen Jungen mit einer atypischen Inzidenz eines großen Trigeminus-Schwannoms mit schmerzloser Malokklusion und einseitiger Kaukraftschwäche präsentiert wurde. Dieser Fall ist nach unserem Kenntnisstand der erste dokumentierte Fall, bei dem ein Trigeminus-Schwannom eine echte Malokklusion mit Masseterschwäche verursachte, und ist der 19. dokumentierte Fall einer einseitigen Trigeminus-Motorneuropathie verschiedener Ätiologie. Aus einer Studie von Ajay Agarwal[5] geht jedoch hervor, dass intrakranielle Trigeminus-Schwannome seltene Tumoren sind. Die Patienten präsentieren sich in der Regel mit Symptomen einer Funktionsstörung des Trigeminusnervs, wobei das häufigste Symptom Gesichtsschmerzen sind.

Multiple sclerosis and trigeminal reflexes

We must make a further premise regarding axonal demyelination in multiple sclerosis. A study by Joanna Kamińska et el.[6] demonstrated that multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and demyelinating disease of autoimmune origin. The main agents responsible for the development of MS include exogenous, environmental and genetic factors. MS is characterized by multifocal and temporally scattered damage to the Central Nervous System (CNS) leading to axonal damage. Among the clinical courses of MS we can distinguish relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPSM), primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) and relapsing progressive multiple sclerosis (RPMS). Depending on the severity of the signs and symptoms, MS can be described as benign MS or malignant MS. The diagnosis of MS is based on the McDonald's diagnostic criteria, which link the clinical manifestation with the characteristic lesions demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); by analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and visual evoked potentials. It should be emphasized that, despite enormous progress regarding MS and the availability of different diagnostic methods, this disease still represents a diagnostic challenge. It may result from the fact that MS has a different clinical course and lacks a single test of appropriate diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for rapid and accurate diagnosis. Precisely in reference to this last observation we must point out another significant data that emerged from a study by S K Yates and W F Brown[7] in which we read that the jaw jerk of the masseter is present in all control subjects but commonly absent in patients with sclerosis defined multiple (SM). In some MS patients the latency was prolonged. Jaw jerk abnormalities, however, are less frequent than blink reflex responses to supraorbital nerve stimulation. However, there have been patients in whom the blink reflex was normal but the jaw jerk responses were abnormal.

The latter observation suggests that the jaw jerk may occasionally be useful in the detection of brainstem lesions in MS.

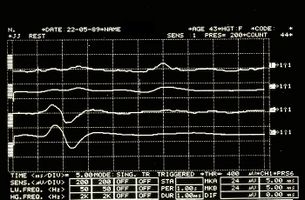

But at this point the doubt becomes reality: what should we think, then, of the anomalies of the trigeminal reflexes that emerged in our Mary Poppins? Could we be facing a form of 'Multiple Sclerosis? How do we distinguish the location of any demyenization whether Central or Peripheral? (Figure 3 and 4)

Pleomorphic adenoma

Pleomorphic adenoma is a common benign neoplasm of the salivary glands characterized by neoplastic proliferation of epithelial (ductal) cells together with myoepithelial components, with malignant potential. It is the most common type of salivary gland tumor and the most common tumor of the parotid gland. It derives its name from architectural pleomorphism (variable appearance) seen under an optical microscope. It is also known as a "mixed tumor, salivary gland type", which refers to its dual origin from epithelial and myoepithelial elements in contrast to its pleomorphic appearance.

The diagnosis of salivary gland tumors uses both tissue sampling and radiographic studies. Tissue sampling procedures include fine needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy (larger needle than FNA). Both of these procedures can be performed on an outpatient basis. Diagnostic imaging techniques for salivary gland tumors include ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT allows direct bilateral visualization of the salivary gland tumor and provides information on overall size and tissue invasion. CT is excellent for demonstrating bony invasion. MRI provides superior delineation of soft tissues such as perineural invasion compared to CT alone as well described by Mehmet Koyuncu et al.[8]

This last observation is very important because an invasion of the tumor of the nervous tissues in the infratemporal fossa cannot be excluded and precisely because of the complexity of the disease, we report a work by Rosalie A Machado et al.[9], which can be explored in depth in the sub-chapter of Masticationpedia 'Intermittent facial spasms as the presenting sign of a recurrent pleomorphic adenoma' in which the authors confirm that to date the development of facial spasms has not been reported in parotid neoplasms. The most common etiologies for hemifacial spasm are vascular compression of the facial nerve ipsilateral to the cerebellopontine angle (defined as primary or idiopathic) (62%), hereditary (2%), secondary to Bell's palsy or facial nerve injury (17 %) and imitators of hemifacial spasms (psychogenic, tics, dystonia, myoclonus, myokymia, myorrhythmia and hemimasticatory spasm) (17%).

Scleroderma

Tiago Nardi Amaral et al.[10] described the clinical characteristics, neuroimaging, and treatment of neurological involvement in systemic sclerosis (SSc) and localized scleroderma (LS) through a systematic review

The authors carried out a literature search in PubMed using the following MeSH terms, scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, localized scleroderma, localized scleroderma "en coup de sabre", Parry-Romberg syndrome, cognitive impairment, memory, seizures, epilepsy, headache , depression, anxiety, mood disorders, Center for Epidemiological Studies in Depression (CES-D), SF-36, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9 ), neuropsychiatry, psychosis, neurological involvement, neuropathy, peripheral nerves, cranial nerves, carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar entrapment, tarsal tunnel syndrome, mononeuropathy, polyneuropathy, radiculopathy, myelopathy, autonomic nervous system, nervous system, electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Patients with other connective tissue diseases responsible for nervous system involvement were excluded from the analyses.

A total of 182 case reports/studies addressing SSc and 50 reporting LS were identified. The total number of patients with SSc was 9,506, while data were available on 224 patients with LS. In LS, convulsions (41.58%) and headache (18.81%) predominated. However, descriptions of various cranial nerve involvement and hemiparesis have been made. Central Nervous System involvement in SSc was characterized by headache (23.73%), seizures (13.56%), and cognitive impairment (8.47%). Depression and anxiety were frequently observed (73.15% and 23.95%, respectively). Myopathy (51.8%), trigeminal neuropathy (16.52%), peripheral sensorimotor polyneuropathy (14.25%), and carpal tunnel syndrome (6.56%) were the most frequent peripheral nervous system involvement in SSc. Autonomic neuropathy involving the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal systems has been regularly described. The treatment of nervous system involvement, however, varied from case to case. However, in more severe cases corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide were usually prescribed.

But this is not all because there are some variants of scleroderma such as Morphea diagnosed in our poor patient Mary Poppins who among other things did not respond positively to cortisone therapy.

Morphea

Morphea is a form of scleroderma that involves isolated patches of hardened skin on the face, hands and feet, or anywhere else on the body, without involvement of internal organs. Morphea most often presents as macules or plaques a few centimeters in diameter, but can also present as bands or in guttate lesions or nodules.[11] Morphea is a thickening and hardening of the skin and subcutaneous tissues due to excessive collagen deposition . Morphea encompasses specific conditions ranging from very small plaques involving only the skin to widespread disease causing functional and cosmetic deformities. Morphea is distinguished from systemic sclerosis by its presumed lack of involvement of internal organs.[12]

Unfortunately the path is still difficult because the long series of variants does not exclude a form of Morphea-induced hemimasticatory spasm as well described by H J Kim et al.[13] in which it is asserted that on the basis of trigeminal clinical and electrophysiological findings such as the blink reflex, the jaw jerk and the masseteric silent period, focal demyelination of the motor branches of the trigeminal nerve due to deep tissue alterations is suggested as a cause of electrical activities abnormal excitatory movements resulting in involuntary chewing movement and spasm.

The latter assertion indicates an involvement of normal and ephaptic excitatory electrical activities.

Conclusion

Before discussing the paths implemented to reach the diagnosis of 'Hemimasticatory spasm' of our poor patient Mary Poppins, we should anticipate that the encrypted code that we were trying to identify as a communication phenomenon concerns 'ephaptic transmission', a very important and complex phenomenon to evoke but above all requires a description of the electrical transmission between neurons.

Electrical signaling is a key feature of the nervous system and gives it the ability to react quickly to changes in the environment. Although synaptic communication between nerve cells is primarily perceived as chemically mediated, electrical synaptic interactions also occur. Two different strategies are responsible for electrical communication between neurons. One is the consequence of low-resistance intercellular pathways, called “gap junctions,” for the diffusion of electrical currents between the inside of two cells. The second occurs in the absence of cell-cell contacts and is a consequence of the extracellular electric fields generated by the electrical activity of neurons. In the chapter dedicated to this fundamental topic, current notions on electrical transmission will be discussed in a historical perspective, comparing the contributions of the two different forms of electrical communication to brain function. ( see Two Forms of Electrical Transmission Between Neurons*)

- ↑ Joseph Jankovic. Peripherally induced movement disorders Neurol Clin. 2009 Aug;27(3):821-32, vii, doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.04.005.

- ↑ Seung Hwan Lee 1, Bong Arm Rhee, Seok Keun Choi, Jun Seok Koh, Young Jin Lim. Cerebellopontine angle tumors causing hemifacial spasm: types, incidence, and mechanism in nine reported cases and literature review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010 Nov;152(11):1901-8. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0796-1.Epub 2010 Sep 16.

- ↑ S Peker, K Ozduman, T Kiliç, M N Pamir. Relief of hemifacial spasm after radiosurgery for intracanalicular vestibular schwannoma. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2004 Aug;47(4):235-7. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-818485.

- ↑ Brandon Emilio Bertot, Melissa Lo Presti, Katie Stormes, Jeffrey S Raskin, Andrew Jea, Daniel Chelius, Sandi Lam. Trigeminal schwannoma presenting with malocclusion: A case report and review of the literature.Surg Neurol Int. 2020 Aug 8;11:230. doi: 10.25259/SNI_482_2019.eCollection 2020.

- ↑ Ajay Agarwal. Intracranial trigeminal schwannoma Ajay Agarwal. Neuroradiol J.2015 Feb;28(1):36-41. doi: 10.15274/NRJ-2014-10117.

- ↑ Joanna Kamińska, Olga M Koper, Kinga Piechal, Halina Kemona . Multiple sclerosis - etiology and diagnostic potential.Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2017 Jun 30;71(0):551-563.doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3836.

- ↑ S K Yates, W F Brown. The human jaw jerk: electrophysiologic methods to measure the latency, normal values, and changes in multiple sclerosis.Neurology. 1981 May;31(5):632-4.doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.5.632.

- ↑ Mehmet Koyuncu, Teoman Seşen, Hüseyin Akan, Ahmet A Ismailoglu, Yücel Tanyeri, Atilla Tekat, Recep Unal, Lütfi Incesu. Comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of parotid tumors.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Dec;129(6):726-32.doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.07.009.

- ↑ . 2017 Feb 10;8(1):86-90. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.86. Rosalie A Machado, Sami P Moubayed, Azita Khorsandi, Juan C Hernandez-Prera, Mark L Urken. Intermittent facial spasms as the presenting sign of a recurrent pleomorphic adenoma. World J Clin Oncol. 2017 Feb 10;8(1):86-90. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.86.

- ↑ Tiago Nardi Amaral, Fernando Augusto Peres, Aline Tamires Lapa, João Francisco Marques-Neto, Simone Appenzeller. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma: a systematic review Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Dec;43(3):335-47. doi: 10.1016/ j.semarthrit. 2013.05.002. Epub 2013 Jul 1.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 171. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 171. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ H J Kim, B S Jeon, K W Lee. Hemimasticatory spasm associated with localized scleroderma and facial hemiatrophy.Arch Neurol. 2000 Apr;57(4):576-80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.4.576.