Difference between revisions of "Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation"

(Created page with "In questo capitolo prendiamo in considerazione un altro argomento molto dibattuto su cui ancora non c'è una opinione univoca nella Comunità Scientifica Internazionale. Questa premessa viene confermata dal fatto che nonostante lo Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) abbia categoricamente invalidato la procedura clinica nella diagnostica dei pazienti affetti da Disordini Temporomandibolari, ancora viene considerata valida. Questo controsenso può essere verificato dalla es...") |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{main menu}}{{ArtBy| | |||

{| | | autore = Gianni Frisardi | ||

| | | autore2 = | ||

| autore3 = | |||

| | }} | ||

| | |||

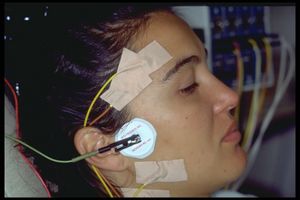

[[File:Myomonitor.jpg|left|frameless]] | |||

In this chapter, we consider another highly debated topic: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), on which there is still no unanimous opinion within the International Scientific Community. This premise is confirmed by the fact that, although the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) have categorically invalidated the clinical procedure in diagnosing patients with Temporomandibular Disorders, the procedure is still considered valid. It continues to be discussed, articles are published, and it is still practiced. This inconsistency is demonstrated by scientific papers in the literature with intermediate and ambiguous conclusions, which generate only questions without providing valid answers. | |||

The RDC has clinically deemed the TENS procedure invalid based on the freeway space and myocentric trajectory, both as diagnostic elements for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) and as part of masticatory prosthetic rehabilitation treatment. As can be seen from the specific section of Table 1 presented in the chapter [[Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)]], it is clear that both freeway space and TENS trajectory were excluded due to a low predictive value (PPV: 0.17). While this might be true, it is essential to delve into the technical and methodological details to understand the rationale behind this decision. For this reason, we will briefly but thoroughly describe the TENS method to better understand its weaknesses and strengths. | |||

'''TENS and Temporomandibular Disorders:''' The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a hinge joint with biarticular properties, enabling the complex movements required for chewing. Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) occurs when the TMJ and associated anatomical structures are affected. Approximately 25% of individuals worldwide show signs or symptoms of TMD. TMD occurs 1.5 to 2.5 times more frequently in women than in men. | |||

Various therapeutic approaches are being studied for managing TMD, aiming to relieve pain and improve jaw function. Although surgical and non-surgical methods are available for treating TMD, conservative treatment is the initial and primary option. Pharmacological therapies include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antidepressants, and muscle relaxants. Another treatment component consists of occlusal and physical therapy techniques, such as low-level laser therapy (LLLT) and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation of the trigeminal nerve (TENS). | |||

TENS has gained recognition as a non-invasive and drug-free technique for pain management in TMD. It involves applying low-frequency electrical currents to the skin through surface electrodes. These currents stimulate sensory nerves and modulate pain signals transmitted to the central nervous system (CNS), altering pain perception. TENS is used in TMD patients to target muscles and nerves surrounding the TMJ, promoting muscle relaxation, reducing muscle spasms, and relieving discomfort. | |||

. | |||

'''Conclusion:''' Despite the controversy surrounding TENS in the treatment of TMD, studies show varying degrees of efficacy in pain reduction and muscle relaxation. However, its role compared to other treatment modalities remains unclear and requires further research to establish its definitive clinical utility.{{Login or request Member account}} | |||

Latest revision as of 11:33, 26 November 2024

Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation

In this chapter, we consider another highly debated topic: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), on which there is still no unanimous opinion within the International Scientific Community. This premise is confirmed by the fact that, although the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) have categorically invalidated the clinical procedure in diagnosing patients with Temporomandibular Disorders, the procedure is still considered valid. It continues to be discussed, articles are published, and it is still practiced. This inconsistency is demonstrated by scientific papers in the literature with intermediate and ambiguous conclusions, which generate only questions without providing valid answers.

The RDC has clinically deemed the TENS procedure invalid based on the freeway space and myocentric trajectory, both as diagnostic elements for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) and as part of masticatory prosthetic rehabilitation treatment. As can be seen from the specific section of Table 1 presented in the chapter Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), it is clear that both freeway space and TENS trajectory were excluded due to a low predictive value (PPV: 0.17). While this might be true, it is essential to delve into the technical and methodological details to understand the rationale behind this decision. For this reason, we will briefly but thoroughly describe the TENS method to better understand its weaknesses and strengths.

TENS and Temporomandibular Disorders: The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a hinge joint with biarticular properties, enabling the complex movements required for chewing. Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) occurs when the TMJ and associated anatomical structures are affected. Approximately 25% of individuals worldwide show signs or symptoms of TMD. TMD occurs 1.5 to 2.5 times more frequently in women than in men.

Various therapeutic approaches are being studied for managing TMD, aiming to relieve pain and improve jaw function. Although surgical and non-surgical methods are available for treating TMD, conservative treatment is the initial and primary option. Pharmacological therapies include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antidepressants, and muscle relaxants. Another treatment component consists of occlusal and physical therapy techniques, such as low-level laser therapy (LLLT) and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation of the trigeminal nerve (TENS).

TENS has gained recognition as a non-invasive and drug-free technique for pain management in TMD. It involves applying low-frequency electrical currents to the skin through surface electrodes. These currents stimulate sensory nerves and modulate pain signals transmitted to the central nervous system (CNS), altering pain perception. TENS is used in TMD patients to target muscles and nerves surrounding the TMJ, promoting muscle relaxation, reducing muscle spasms, and relieving discomfort. .

Conclusion: Despite the controversy surrounding TENS in the treatment of TMD, studies show varying degrees of efficacy in pain reduction and muscle relaxation. However, its role compared to other treatment modalities remains unclear and requires further research to establish its definitive clinical utility.

To read the full text of this chapter, log in or request an account

A Google Account is needeed to request a Member Account