Difference between revisions of "La logica del linguaggio classico"

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

{{Bookind2}} | {{Bookind2}} | ||

== | ==Introduzione== | ||

Ci siamo separati nel capitolo precedente sulla "[[Logica del linguaggio medico]]" nel tentativo di spostare l'attenzione dal sintomo o dai segni clinici al linguaggio macchina crittografato per il quale, le argomentazioni di Donald E Stanley, Daniel G Campos e Pat Croskerry sono benvenute, ma connesso al tempo '''<math>t_n</math>''' come vettore di informazione (anticipazione del sintomo) e al messaggio come linguaggio macchina e non come linguaggio non verbale)<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Stanley DE | | autore = Stanley DE | ||

| autore2 = Campos DG | | autore2 = Campos DG | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref><br> | }}</ref><br>Ciò ovviamente non preclude la validità della storia clinica costruita su un linguaggio verbale pseudo-formale ormai ben radicato nella realtà clinica e che ha già dimostrato la sua autorevolezza diagnostica. Il tentativo di spostare l'attenzione su un linguaggio macchina e sul Sistema non offre altro che un'opportunità per la validazione della Scienza Medico-Diagnostica. | ||

Siamo decisamente consapevoli che il nostro Sapiens Linux è ancora perplesso su ciò che è stato anticipato e continua a chiedersi{{q4|la logica del linguaggio classico potrebbe aiutarci a risolvere il dilemma della povera Mary Poppins?|un po' di pazienza, per favore}} | |||

Non possiamo fornire una risposta convenzionale perché la scienza non progredisce con asserzioni che non sono giustificate da domande e riflessioni scientificamente validate; ed è proprio questo il motivo per cui cercheremo di dar voce ad alcuni pensieri, perplessità e dubbi espressi su alcuni temi basilari portati in discussione in alcuni articoli scientifici. | |||

Uno di questi temi fondamentali è la 'Biologia craniofacciale'. | |||

Cominciamo con un noto studio di Townsend e Brook:<ref name=":0">{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Townsend GC | | autore = Townsend GC | ||

| autore2 = Brook AH | | autore2 = Brook AH | ||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> in questo lavoro gli autori mettono in discussione lo status quo della ricerca sia fondamentale che applicata in "Biologia craniofacciale" per estrarre considerazioni e implicazioni cliniche. Un argomento trattato è stato l'"Approccio interdisciplinare", in cui Geoffrey Sperber e suo figlio Steven hanno visto la forza del progresso esponenziale della "biologia craniofacciale" nelle innovazioni tecnologiche come il sequenziamento genico, la scansione TC, l'imaging MRI, la scansione laser, l'analisi delle immagini , ecografia e spettroscopia.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Sperber GH | | autore = Sperber GH | ||

| autore2 = Sperber SM | | autore2 = Sperber SM | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

Un altro argomento di grande interesse per l'implementazione della 'Biologia Craniofacciale' è la consapevolezza che i sistemi biologici sono 'Sistemi Complessi'<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Brook AH | | autore = Brook AH | ||

| autore2 = Brook O'Donnell M | | autore2 = Brook O'Donnell M | ||

| Line 113: | Line 115: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> e che l<nowiki>''Epigenetica' gioca un ruolo chiave nella biologia molecolare craniofacciale. I ricercatori di Adelaide e Sydney forniscono una rassegna critica nel campo dell'</nowiki>epigenetica rivolta, appunto, alle discipline odontoiatriche e craniofacciali.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Williams SD | | autore = Williams SD | ||

| autore2 = Hughes TE | | autore2 = Hughes TE | ||

| Line 133: | Line 135: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> La fenomica, in particolare, discussa da questi autori (vedi [[Fenomica]])) è un campo di ricerca generale che prevede la misurazione dei cambiamenti nei denti e nelle strutture orofacciali associate risultanti dalle interazioni tra fattori genetici, epigenetici e ambientali durante lo sviluppo.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Yong R | | autore = Yong R | ||

| autore2 = Ranjitkar S | | autore2 = Ranjitkar S | ||

| Line 156: | Line 158: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> In | }}</ref> In questo stesso contesto, va evidenziato il lavoro di Irma Thesleff di Helsinki, Finlandia. Spiega nel suo lavoro che ci sono una serie di centri di segnalazione transitori nell'epitelio dentale che svolgono ruoli importanti nel programma di sviluppo dei denti.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Thesleff I | | autore = Thesleff I | ||

| titolo = Current understanding of the process of tooth formation: transfer from the laboratory to the clinic | | titolo = Current understanding of the process of tooth formation: transfer from the laboratory to the clinic | ||

| Line 172: | Line 174: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> Inoltre ci sono altri lavori, di Peterkova R, Hovor akova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, che forniscono un'affascinante rassegna dei processi che si verificano durante lo sviluppo dentale;<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Peterkova R | | autore = Peterkova R | ||

| autore2 = Hovorakova M | | autore2 = Hovorakova M | ||

| Line 235: | Line 237: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> per completezza, non dimentichiamo i lavori di Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S e Bartold PM., che esaminano un'ampia documentazione su cellule staminali, ingegneria tissutale e rigenerazione parodontale.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Han J | | autore = Han J | ||

| autore2 = Menicanin D | | autore2 = Menicanin D | ||

| Line 256: | Line 258: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

In | |||

In questa rassegna non potevano mancare argomentazioni sulle influenze genetiche, epigenetiche e ambientali durante la morfogenesi che portano a variazioni nel numero, dimensioni e forma del dente<ref>{{Cite book | |||

<nowiki> </nowiki><nowiki>|</nowiki> autore = Brook AH | <nowiki> </nowiki><nowiki>|</nowiki> autore = Brook AH | ||

<nowiki> </nowiki><nowiki>|</nowiki> autore2 = Jernvall J | <nowiki> </nowiki><nowiki>|</nowiki> autore2 = Jernvall J | ||

| Line 291: | Line 294: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref>e sull'influenza della pressione della lingua sulla crescita e sulla funzione craniofacciale.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Kieser JA | | autore = Kieser JA | ||

| autore2 = Farland MG | | autore2 = Farland MG | ||

| Line 328: | Line 331: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref>Townsend | }}</ref> Anche il lavoro straordinario di Townsend e Brook merita una menzione, e il contenuto intrinseco di quanto in esso riportato combacia ugualmente bene con un altro lodevole autore: HC Slavkin. Slavkin<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Slavkin HC | | autore = Slavkin HC | ||

| titolo = The Future of Research in Craniofacial Biology and What This Will Mean for Oral Health Professional Education and Clinical Practice | | titolo = The Future of Research in Craniofacial Biology and What This Will Mean for Oral Health Professional Education and Clinical Practice | ||

| Line 344: | Line 347: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> afferma che: | ||

:"Il futuro è pieno di opportunità significative per migliorare i risultati clinici delle malformazioni craniofacciali congenite e acquisite. I medici svolgono un ruolo chiave poiché il pensiero critico e il pubblico clinico migliorano sostanzialmente l'accuratezza diagnostica e quindi i risultati clinici sulla salute". | |||

{{q4|Capisco il progresso della Scienza descritto dagli autori ma non capisco il cambiamento di pensiero|Ti faccio un esempio pratico}} | |||

Nel capitolo "[[Introduzione]]" abbiamo posto alcune domande sul tema della malocclusione ma in questo contesto simuliamo la logica del linguaggio medico del dentista di fronte al caso clinico presentato nel "Capitolo introduttivo" con le sue conclusioni diagnostiche e terapeutiche. | |||

Il paziente presenta un morso incrociato unilaterale posteriore e un morso aperto anteriore.<ref> | |||

{{cita libro | {{cita libro | ||

|autore=Littlewood SJ | |autore=Littlewood SJ | ||

| Line 369: | Line 371: | ||

|DOI=10.1111/adj.12475 | |DOI=10.1111/adj.12475 | ||

|OCLC= | |OCLC= | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> Il morso incrociato è un altro elemento di disturbo della normale occlusione<ref>{{cita libro | ||

|autore=Miamoto CB | |autore=Miamoto CB | ||

|autore2=Silva Marques L | |autore2=Silva Marques L | ||

| Line 385: | Line 387: | ||

|DOI= | |DOI= | ||

|OCLC= | |OCLC= | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> per il quale viene trattato obbligatoriamente insieme al morso aperto.<ref>{{cita libro | ||

|autore=Alachioti XS | |autore=Alachioti XS | ||

|autore2=Dimopoulou E | |autore2=Dimopoulou E | ||

| Line 415: | Line 417: | ||

|DOI=10.1179/bjo.5.1.21 | |DOI=10.1179/bjo.5.1.21 | ||

|OCLC= | |OCLC= | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> Questo tipo di ragionamento significa che il modello (sistema masticatorio) è 'normalizzato all'occlusione'; e letto al contrario, significa che la discrepanza occlusale è causa di malocclusione, quindi una malattia del Sistema Masticatorio, e quindi è giustificabile un intervento per ripristinare la fisiologica funzione masticatoria. (Figura 1a). | ||

Questo esempio è il linguaggio logico classico, come spiegheremo in dettaglio, ma ora sorge un dubbio:<blockquote> | |||

Nel momento in cui gli assiomi ortodontici e ortognatici stavano costruendo protocolli confermati dalla Comunità Scientifica Internazionale, erano a conoscenza delle informazioni di cui abbiamo discusso nell'introduzione a questo capitolo?</blockquote> | |||

Non certamente, perché il tempo '''<math>t_n</math>''' è '''portatore di informazione''' e nonostante questo limite cognitivo si procede con una Logica del Linguaggio Classico molto discutibile per l'incolumità del cittadino. | |||

{{q2|questa affermazione mi sembra un po' rischiosa!|certo, ma la sequenza logica è già stata anticipata}} | |||

Se lo stesso caso fosse interpretato con una mentalità che seguisse una 'logica del linguaggio di sistema' (ne parleremo nell'apposito capitolo), le conclusioni sarebbero sorprendenti. | |||

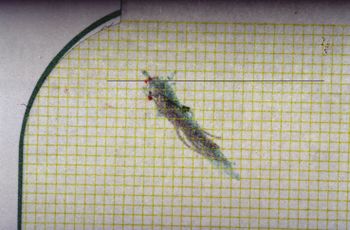

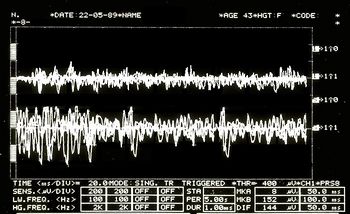

Se osserviamo le risposte elettrofisiologiche eseguite sul paziente con malocclusione nelle figure 1b, 1c e 1d (con la spiegazione fatta direttamente in didascalia per semplificare la discussione), noteremo che questi dati possono farci pensare a tutto tranne che a una 'Malocclusione ' e, quindi, gli assiomi di tipo ortodontico e ortognatico 'causa/effetto' lasciano un vuoto concettuale.<gallery widths="350" heights="282" perrow="2" mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:Occlusal Centric view in open and cross bite patient.jpg|''' | File:Occlusal Centric view in open and cross bite patient.jpg|'''Figura 1a:''' Paziente con malocclusione, morso aperto e morso incrociato posteriore destro che in termini riabilitativi deve essere trattato con terapia ortodontica e/o chirurgia ortognatica | ||

File:Bilateral Electric Transcranial Stimulation.jpg|''' | File:Bilateral Electric Transcranial Stimulation.jpg|'''Figura 1b:''' Potenziale evocato motorio dalla stimolazione elettrica transcranica delle radici del trigemino. Notare la simmetria strutturale calcolata dall'ampiezza picco-picco sui masseteri sinistro e destro (tracce rispettivamente superiore e inferiore) | ||

File:Jaw Jerk .jpg|''' | File:Jaw Jerk .jpg|'''Figura 1c:''' Riflesso mandibolare evocato o jerk mandibolare mediante percussione del mento attraverso un martello neurologico innescato. Notare la simmetria funzionale calcolata dall'ampiezza picco-picco sui masseteri sinistro e destro (tracce rispettivamente superiore e inferiore) | ||

File:Mechanic Silent Period.jpg|''' | File:Mechanic Silent Period.jpg|'''Figura 1d:''' Periodo di silenzio meccanico evocato dalla percussione del mento attraverso un martello neurologico innescato. Si noti la simmetria funzionale calcolata sull'area integrale dei masseteri di destra e di sinistra (tracce rispettivamente superiore e inferiore). | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

{{q4| | {{q4|Fammi capire meglio cosa c'entra la logica del linguaggio classico con esso|Lo faremo seguendo il caso clinico della nostra Mary Poppins}} | ||

== | ==Formalismo matematico== | ||

In | In questo capitolo, riconsidereremo il caso clinico della sfortunata Mary Poppins affetta da Dolore Orofacciale da più di 10 anni a cui il suo dentista ha diagnosticato un 'Disturbo Temporomandibolare' (TMD) o meglio Dolore Orofacciale da TMD. Per comprendere meglio perché l'esatta formulazione diagnostica rimane complessa con una Logica del linguaggio classico, occorre comprendere il concetto su cui si basa la filosofia del linguaggio classico con una breve introduzione all'argomento. | ||

=== | ===Proposizioni=== | ||

La logica classica si basa su proposizioni. Si dice spesso che una proposizione è una frase che chiede se la proposizione è vera o falsa. In effetti, una proposizione in matematica di solito è vera o falsa, ma questa è ovviamente un po' troppo vaga per essere una definizione. Può essere preso, nel migliore dei casi, come un monito: se una frase, espressa con un linguaggio comune, non ha senso chiedersi se è vera o falsa, non sarà una proposizione ma qualcos'altro. | |||

Si può argomentare se le frasi del linguaggio comune siano o meno proposizioni poiché in molti casi non è spesso evidente se una certa affermazione è vera o falsa. | |||

'' | ''Fortunatamente, le proposizioni matematiche, se ben espresse, non mostrano tali ambiguità».'' | ||

Proposizioni più semplici possono essere combinate tra loro per formare proposizioni nuove e più complesse. Ciò avviene con l'ausilio di operatori detti operatori logici e connettivi quantificatori che possono essere ridotti ai seguenti<ref><!--68-->For the sake of simplicity of exposition and reading, we will deal in this chapter with the ''symbol of belonging'', the ''symbol of consequence'' and the "''such that''" as if they were quantifiers and connectives of propositions in classical logic.<br><!--69-->Strictly speaking, within classical logic they should not be treated as such, but even if we do, this does not absolutely change the meaning of the speech and no inconsistencies of any kind are created.</ref>: | |||

# | #Congiunzione, che è indicata dal simbolo <math>\land</math> (e): | ||

# | #Disgiunzione, indicata dal simbolo <math>\lor</math> (): | ||

# | #Negazione, indicata dal simbolo<math>\urcorner</math> (non): | ||

# | #Implicazione, indicata dal simbolo<math>\Rightarrow</math> (se...solo se): | ||

# | #Conseguenza, indicata dal simbolo <math>\vdash</math> (è una partizione di.....): | ||

# | #Quantificatore universale, indicato dal simbolo <math>\forall</math> (per tutti): | ||

# | #Dimostrazione, indicata dal simbolo <math>\mid</math> (così che): | ||

# | #Adesione, che è indicata dal simbolo <math>\in</math> (è un elemento di) o dal simbolo <math>\not\in</math> (non è un elemento di): | ||

=== | ===Dimostrazione per assurdità=== | ||

Inoltre, nella logica classica esiste un principio chiamato terzo escluso che afferma che una proposizione che non può essere falsa deve essere considerata vera poiché non esiste una terza possibilità. | |||

Supponiamo di dover dimostrare che la proposizione <math>p</math> è vero. La procedura consiste nel dimostrare che l'assunzione che <math>p</math> è falso porta a una contraddizione logica. Così la proposizione <math>p</math> non può essere falso, e quindi, secondo la legge del terzo escluso, deve essere vero. Questo metodo di dimostrazione è chiamato dimostrazione per assurdo.<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Pereira LM | | autore = Pereira LM | ||

| autore2 = Pinto AM | | autore2 = Pinto AM | ||

| Line 476: | Line 480: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

=== | ===Predicati=== | ||

Ciò che abbiamo brevemente descritto finora è la logica delle proposizioni. Una proposizione afferma qualcosa su oggetti matematici specifici come: "2 è maggiore di 1, quindi 1 è minore di 2" o "un quadrato non ha 5 lati, quindi un quadrato non è un pentagono". Molte volte, però, le affermazioni matematiche non riguardano il singolo oggetto, ma oggetti generici di un insieme quali: '''<math>X</math>'' sono più alti di 2 metri 'dove ''<math>X</math>'' denota un gruppo generico (ad esempio tutti i giocatori di pallavolo). In questo caso si parla di predicati. | |||

Intuitivamente, un predicato è una frase che riguarda un insieme di elementi (che nel nostro caso medico saranno i pazienti) e che afferma qualcosa su di essi. | |||

{{q4|Allora la povera Mary Poppins è una malata di TMD oppure no!|vediamo cosa ci dice la logica del linguaggio classico}} | |||

Oltre alle conferme derivate dalla logica del linguaggio medico discussa nel capitolo precedente, il collega dentista acquisisce altri dati strumentali che gli consentono di confermare la sua diagnosi. Questi ultimi test riguardano l'analisi dei tracciati assiografici mediante l'utilizzo di una frizione paraocclusale funzionale personalizzata che consente la visualizzazione e la quantificazione dei tracciati condilari nelle funzioni masticatorie. Come si vede dalla Figura 4 l'appiattimento delle tracce condilari sul lato destro sia nella cinetica masticatoria mediotrusiva (colore verde) che nei cicli di apertura e protrusione (colore grigio) confermano l'appiattimento anatomico e funzionale dell'ATM destra nella dinamica masticare. Oltre all'assiografia, il collega esegue un'elettromiografia di superficie sui masseteri (Fig. 6) chiedendo al paziente di esercitare il massimo della sua forza muscolare. Questo tipo di analisi elettromiografica è chiamata "EMG Interferential Pattern" a causa del contenuto ad alta frequenza dei picchi che subiscono l'interferenza di fase. Infatti la Figura 6 mostra un'asimmetria nel reclutamento delle unità motorie del massetere destro (traccia superiore) rispetto a quelle del massetere sinistro (traccia inferiore).<ref>{{cite book | |||

| autore = Castroflorio T | | autore = Castroflorio T | ||

| autore2 = Talpone F | | autore2 = Talpone F | ||

| Line 553: | Line 560: | ||

| oaf = <!-- qualsiasi valore --> | | oaf = <!-- qualsiasi valore --> | ||

}}</ref><center> | }}</ref><center> | ||

== | ==2° Approccio Clinico == | ||

( | (Passa il mouse sopra le immagini) | ||

<gallery widths="350" heights="282" perrow="2" mode="slideshow"> | <gallery widths="350" heights="282" perrow="2" mode="slideshow"> | ||

File:Spasmo emimasticatorio.jpg|''' | File:Spasmo emimasticatorio.jpg|'''Figura 2:''' Paziente che riporta 'Dolore orofacciale' nella faccia emilaterale destra | ||

File:Spasmo emimasticatorio ATM.jpg|''' | File:Spasmo emimasticatorio ATM.jpg|'''Figura 3:''' Stratigrafia dell'ATM del paziente che mostra segni di appiattimento condilare e osteofiti | ||

File:Atm1 sclerodermia.jpg|''' | File:Atm1 sclerodermia.jpg|'''Figura 4:''' Tomografia computerizzata dell'ATM | ||

File:Spasmo emimasticatorio assiografia.jpg|''' | File:Spasmo emimasticatorio assiografia.jpg|'''Figura 5:''' Assiografia del paziente che mostra un appiattimento del pattern masticatorio sul condilo destro | ||

File:EMG2.jpg|''' | File:EMG2.jpg|'''Figura 6:''' Attività interferente EMG. Tracce superiori sovrapposte corrispondenti al massetere destro, in basso al massetere sinistro. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

===== | ===== Proposizioni nel contesto odontoiatrico ===== | ||

Mentre cerchiamo di utilizzare il formalismo matematico per tradurre le conclusioni raggiunte dal dentista con il linguaggio logico classico, consideriamo i seguenti predicati: | |||

*''x'' <math>\equiv</math> | *''x'' <math>\equiv</math> Pazienti normali (normale sta per pazienti comunemente presenti in ambito specialistico) | ||

*<math>A(x) \equiv</math> Rimodellamento osseo con osteofito da esame stratigrafico e TC condilare; e | |||

*<math>B(x)\equiv</math> Disturbi Temporo-Mandibolari (DTM) con conseguente dolore orofacciale (OP) | |||

*<math>\mathrm{a}\equiv</math> Paziente specifico: Mary Poppins | |||

Qualsiasi paziente normale <math>\forall\text{x} | |||

</math> che risulti positivo all'esame radiografico dell'ATM <math>\mathrm{\mathcal{A}}(\text{x})</math> [Figure 2 e 3] è affetto da TMD <math>\rightarrow\mathrm{\mathcal{B}}(\text{x})</math>; da ciò ne consegue che <math>\vdash</math> essendo Mary Poppins positiva (ed essendo anche una paziente "Normale") alla radiografia dell'ATM <math>A(a)</math> allora anche Mary Poppins è affetta da TMD <math>\rightarrow \mathcal{B}(a)</math>. Il linguaggio dei predicati si esprime nel modo seguente: | |||

<math>\{a \in x \mid \forall \text{x} \; A(\text{x}) \rightarrow {B}(\text{x}) \vdash A( a)\rightarrow B(a) \}</math>. <math>(1)</math> | <math>\{a \in x \mid \forall \text{x} \; A(\text{x}) \rightarrow {B}(\text{x}) \vdash A( a)\rightarrow B(a) \}</math>. <math>(1)</math> | ||

A questo punto, si deve anche considerare che la logica dei predicati non viene utilizzata solo per dimostrare che un particolare insieme di premesse implica una particolare evidenza <math>(1)</math>. Viene anche utilizzata per dimostrare che una particolare affermazione non è vera, o che un particolare pezzo di la conoscenza è logicamente compatibile/incompatibile con una particolare evidenza. | |||

Per provare che questa proposizione è vera dobbiamo usare la suddetta ''dimostrazione per assurdità''. Se la sua negazione crea una contraddizione, sicuramente la proposta del dentista sarà vera: | |||

<math>\urcorner\{a \in x \mid \forall \text{x} \; A(\text{x}) \rightarrow {B}(\text{x}) \vdash A( a)\rightarrow B(a) \}</math>. <math>(2)</math> | <math>\urcorner\{a \in x \mid \forall \text{x} \; A(\text{x}) \rightarrow {B}(\text{x}) \vdash A( a)\rightarrow B(a) \}</math>. <math>(2)</math> | ||

"<math>(2)</math>" afferma che non è vero che coloro che risultano positivi alla TC dell'ATM hanno i DTM, quindi Mary Poppins (paziente normale positivo alla TC dell'ATM) non ha i DTM. | |||

Il dentista ritiene che l'affermazione di Mary Poppins (che non ha la DTM in base a queste premesse) sia una contraddizione, quindi l'affermazione principale è vera. | |||

===Neurophysiological proposition=== | ===Neurophysiological proposition=== | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 28 October 2022

| Other languages: |

La logica classica sarà discussa in questo capitolo. Nella prima parte verrà illustrato il formalismo matematico e le regole che lo compongono. Nella seconda parte verrà fornito un esempio clinico per valutarne l'efficacia nel determinare una diagnosi.

In conclusione, è evidente che una logica classica del linguaggio, che ha un approccio estremamente dicotomico (o qualcosa è bianco, o è nero), non può descrivere le tante sfumature che hanno le situazioni cliniche reali.

Come vedremo presto, questo articolo mostrerà che la logica classica manca della necessaria precisione, costringendoci a migliorarla con altri tipi di linguaggi logici.

Introduzione

Ci siamo separati nel capitolo precedente sulla "Logica del linguaggio medico" nel tentativo di spostare l'attenzione dal sintomo o dai segni clinici al linguaggio macchina crittografato per il quale, le argomentazioni di Donald E Stanley, Daniel G Campos e Pat Croskerry sono benvenute, ma connesso al tempo come vettore di informazione (anticipazione del sintomo) e al messaggio come linguaggio macchina e non come linguaggio non verbale)[1][2]

Ciò ovviamente non preclude la validità della storia clinica costruita su un linguaggio verbale pseudo-formale ormai ben radicato nella realtà clinica e che ha già dimostrato la sua autorevolezza diagnostica. Il tentativo di spostare l'attenzione su un linguaggio macchina e sul Sistema non offre altro che un'opportunità per la validazione della Scienza Medico-Diagnostica.

Siamo decisamente consapevoli che il nostro Sapiens Linux è ancora perplesso su ciò che è stato anticipato e continua a chiedersi

«la logica del linguaggio classico potrebbe aiutarci a risolvere il dilemma della povera Mary Poppins?»

(un po' di pazienza, per favore) |

Non possiamo fornire una risposta convenzionale perché la scienza non progredisce con asserzioni che non sono giustificate da domande e riflessioni scientificamente validate; ed è proprio questo il motivo per cui cercheremo di dar voce ad alcuni pensieri, perplessità e dubbi espressi su alcuni temi basilari portati in discussione in alcuni articoli scientifici.

Uno di questi temi fondamentali è la 'Biologia craniofacciale'.

Cominciamo con un noto studio di Townsend e Brook:[3] in questo lavoro gli autori mettono in discussione lo status quo della ricerca sia fondamentale che applicata in "Biologia craniofacciale" per estrarre considerazioni e implicazioni cliniche. Un argomento trattato è stato l'"Approccio interdisciplinare", in cui Geoffrey Sperber e suo figlio Steven hanno visto la forza del progresso esponenziale della "biologia craniofacciale" nelle innovazioni tecnologiche come il sequenziamento genico, la scansione TC, l'imaging MRI, la scansione laser, l'analisi delle immagini , ecografia e spettroscopia.[4]

Un altro argomento di grande interesse per l'implementazione della 'Biologia Craniofacciale' è la consapevolezza che i sistemi biologici sono 'Sistemi Complessi'[5] e che l''Epigenetica' gioca un ruolo chiave nella biologia molecolare craniofacciale. I ricercatori di Adelaide e Sydney forniscono una rassegna critica nel campo dell'epigenetica rivolta, appunto, alle discipline odontoiatriche e craniofacciali.[6] La fenomica, in particolare, discussa da questi autori (vedi Fenomica)) è un campo di ricerca generale che prevede la misurazione dei cambiamenti nei denti e nelle strutture orofacciali associate risultanti dalle interazioni tra fattori genetici, epigenetici e ambientali durante lo sviluppo.[7] In questo stesso contesto, va evidenziato il lavoro di Irma Thesleff di Helsinki, Finlandia. Spiega nel suo lavoro che ci sono una serie di centri di segnalazione transitori nell'epitelio dentale che svolgono ruoli importanti nel programma di sviluppo dei denti.[8] Inoltre ci sono altri lavori, di Peterkova R, Hovor akova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, che forniscono un'affascinante rassegna dei processi che si verificano durante lo sviluppo dentale;[9][10][11] per completezza, non dimentichiamo i lavori di Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S e Bartold PM., che esaminano un'ampia documentazione su cellule staminali, ingegneria tissutale e rigenerazione parodontale.[12]

In questa rassegna non potevano mancare argomentazioni sulle influenze genetiche, epigenetiche e ambientali durante la morfogenesi che portano a variazioni nel numero, dimensioni e forma del dente[13][14]e sull'influenza della pressione della lingua sulla crescita e sulla funzione craniofacciale.[15][16] Anche il lavoro straordinario di Townsend e Brook merita una menzione, e il contenuto intrinseco di quanto in esso riportato combacia ugualmente bene con un altro lodevole autore: HC Slavkin. Slavkin[17] afferma che:

- "Il futuro è pieno di opportunità significative per migliorare i risultati clinici delle malformazioni craniofacciali congenite e acquisite. I medici svolgono un ruolo chiave poiché il pensiero critico e il pubblico clinico migliorano sostanzialmente l'accuratezza diagnostica e quindi i risultati clinici sulla salute".

«Capisco il progresso della Scienza descritto dagli autori ma non capisco il cambiamento di pensiero»

(Ti faccio un esempio pratico) |

Nel capitolo "Introduzione" abbiamo posto alcune domande sul tema della malocclusione ma in questo contesto simuliamo la logica del linguaggio medico del dentista di fronte al caso clinico presentato nel "Capitolo introduttivo" con le sue conclusioni diagnostiche e terapeutiche.

Il paziente presenta un morso incrociato unilaterale posteriore e un morso aperto anteriore.[18] Il morso incrociato è un altro elemento di disturbo della normale occlusione[19] per il quale viene trattato obbligatoriamente insieme al morso aperto.[20][21] Questo tipo di ragionamento significa che il modello (sistema masticatorio) è 'normalizzato all'occlusione'; e letto al contrario, significa che la discrepanza occlusale è causa di malocclusione, quindi una malattia del Sistema Masticatorio, e quindi è giustificabile un intervento per ripristinare la fisiologica funzione masticatoria. (Figura 1a).

Questo esempio è il linguaggio logico classico, come spiegheremo in dettaglio, ma ora sorge un dubbio:Nel momento in cui gli assiomi ortodontici e ortognatici stavano costruendo protocolli confermati dalla Comunità Scientifica Internazionale, erano a conoscenza delle informazioni di cui abbiamo discusso nell'introduzione a questo capitolo?

Non certamente, perché il tempo è portatore di informazione e nonostante questo limite cognitivo si procede con una Logica del Linguaggio Classico molto discutibile per l'incolumità del cittadino.

(certo, ma la sequenza logica è già stata anticipata)

Se lo stesso caso fosse interpretato con una mentalità che seguisse una 'logica del linguaggio di sistema' (ne parleremo nell'apposito capitolo), le conclusioni sarebbero sorprendenti.

Se osserviamo le risposte elettrofisiologiche eseguite sul paziente con malocclusione nelle figure 1b, 1c e 1d (con la spiegazione fatta direttamente in didascalia per semplificare la discussione), noteremo che questi dati possono farci pensare a tutto tranne che a una 'Malocclusione ' e, quindi, gli assiomi di tipo ortodontico e ortognatico 'causa/effetto' lasciano un vuoto concettuale.«Fammi capire meglio cosa c'entra la logica del linguaggio classico con esso»

(Lo faremo seguendo il caso clinico della nostra Mary Poppins) |

Formalismo matematico

In questo capitolo, riconsidereremo il caso clinico della sfortunata Mary Poppins affetta da Dolore Orofacciale da più di 10 anni a cui il suo dentista ha diagnosticato un 'Disturbo Temporomandibolare' (TMD) o meglio Dolore Orofacciale da TMD. Per comprendere meglio perché l'esatta formulazione diagnostica rimane complessa con una Logica del linguaggio classico, occorre comprendere il concetto su cui si basa la filosofia del linguaggio classico con una breve introduzione all'argomento.

Proposizioni

La logica classica si basa su proposizioni. Si dice spesso che una proposizione è una frase che chiede se la proposizione è vera o falsa. In effetti, una proposizione in matematica di solito è vera o falsa, ma questa è ovviamente un po' troppo vaga per essere una definizione. Può essere preso, nel migliore dei casi, come un monito: se una frase, espressa con un linguaggio comune, non ha senso chiedersi se è vera o falsa, non sarà una proposizione ma qualcos'altro.

Si può argomentare se le frasi del linguaggio comune siano o meno proposizioni poiché in molti casi non è spesso evidente se una certa affermazione è vera o falsa.

Fortunatamente, le proposizioni matematiche, se ben espresse, non mostrano tali ambiguità».

Proposizioni più semplici possono essere combinate tra loro per formare proposizioni nuove e più complesse. Ciò avviene con l'ausilio di operatori detti operatori logici e connettivi quantificatori che possono essere ridotti ai seguenti[22]:

- Congiunzione, che è indicata dal simbolo (e):

- Disgiunzione, indicata dal simbolo ():

- Negazione, indicata dal simbolo (non):

- Implicazione, indicata dal simbolo (se...solo se):

- Conseguenza, indicata dal simbolo (è una partizione di.....):

- Quantificatore universale, indicato dal simbolo (per tutti):

- Dimostrazione, indicata dal simbolo (così che):

- Adesione, che è indicata dal simbolo (è un elemento di) o dal simbolo (non è un elemento di):

Dimostrazione per assurdità

Inoltre, nella logica classica esiste un principio chiamato terzo escluso che afferma che una proposizione che non può essere falsa deve essere considerata vera poiché non esiste una terza possibilità.

Supponiamo di dover dimostrare che la proposizione è vero. La procedura consiste nel dimostrare che l'assunzione che è falso porta a una contraddizione logica. Così la proposizione non può essere falso, e quindi, secondo la legge del terzo escluso, deve essere vero. Questo metodo di dimostrazione è chiamato dimostrazione per assurdo.[23]

Predicati

Ciò che abbiamo brevemente descritto finora è la logica delle proposizioni. Una proposizione afferma qualcosa su oggetti matematici specifici come: "2 è maggiore di 1, quindi 1 è minore di 2" o "un quadrato non ha 5 lati, quindi un quadrato non è un pentagono". Molte volte, però, le affermazioni matematiche non riguardano il singolo oggetto, ma oggetti generici di un insieme quali: ' sono più alti di 2 metri 'dove denota un gruppo generico (ad esempio tutti i giocatori di pallavolo). In questo caso si parla di predicati.

Intuitivamente, un predicato è una frase che riguarda un insieme di elementi (che nel nostro caso medico saranno i pazienti) e che afferma qualcosa su di essi.

«Allora la povera Mary Poppins è una malata di TMD oppure no!»

(vediamo cosa ci dice la logica del linguaggio classico) |

2° Approccio Clinico

(Passa il mouse sopra le immagini)

Proposizioni nel contesto odontoiatrico

Mentre cerchiamo di utilizzare il formalismo matematico per tradurre le conclusioni raggiunte dal dentista con il linguaggio logico classico, consideriamo i seguenti predicati:

- x Pazienti normali (normale sta per pazienti comunemente presenti in ambito specialistico)

- Rimodellamento osseo con osteofito da esame stratigrafico e TC condilare; e

- Disturbi Temporo-Mandibolari (DTM) con conseguente dolore orofacciale (OP)

- Paziente specifico: Mary Poppins

Qualsiasi paziente normale che risulti positivo all'esame radiografico dell'ATM [Figure 2 e 3] è affetto da TMD ; da ciò ne consegue che essendo Mary Poppins positiva (ed essendo anche una paziente "Normale") alla radiografia dell'ATM allora anche Mary Poppins è affetta da TMD . Il linguaggio dei predicati si esprime nel modo seguente:

.

A questo punto, si deve anche considerare che la logica dei predicati non viene utilizzata solo per dimostrare che un particolare insieme di premesse implica una particolare evidenza . Viene anche utilizzata per dimostrare che una particolare affermazione non è vera, o che un particolare pezzo di la conoscenza è logicamente compatibile/incompatibile con una particolare evidenza.

Per provare che questa proposizione è vera dobbiamo usare la suddetta dimostrazione per assurdità. Se la sua negazione crea una contraddizione, sicuramente la proposta del dentista sarà vera:

.

"" afferma che non è vero che coloro che risultano positivi alla TC dell'ATM hanno i DTM, quindi Mary Poppins (paziente normale positivo alla TC dell'ATM) non ha i DTM.

Il dentista ritiene che l'affermazione di Mary Poppins (che non ha la DTM in base a queste premesse) sia una contraddizione, quindi l'affermazione principale è vera.

Neurophysiological proposition

Let us imagine that the neurologist disagrees with the conclusion and asserts that Mary Poppins is not affected by TMDs or that at least it is not the main cause of Orofacial Pain, but that, rather, she is affected by a neuromotor Orofacial Pain (nOP), therefore that she does not belong to the group of 'normal patients' but is to be considered a 'non-specific patient' (uncommon in the specialist context).

Obviously, this dialectic would last indefinitely because both would defend their scientific-clinical context; but let us see what happens in the logic of predicates.

The neurologist's statement would be like:

.

"" means that every patient who is TMJ CT positive has TMDs but even though Mary Poppins is TMJ CT positive, she does not have TMDs.

In order to prove that this proposition is true, we must use once again the above mentioned demonstration by absurdity. If its denial creates a contradiction, surely the neurologist's proposition will be true:

.

Following the logical rules of predicates, there is no reason to say that denial (4) is contradictory or meaningless, therefore the neurologist (unlike the dentist) would not seem to have the logical tools to confirm his conclusion.«then the dentist triumphs!»

(don't take it for granted) |

Compatibility and incompatibility of the statements

The complication lies in the fact that the dentist will present a series of statements as clinical reports such as the stratigraphy and CT of the TMJ, that indicate an anatomical flattening of the joint, axiography of the condylar traces with a reduction in kinematic convexity and a tracing EMG interference pattern in which an asymmetrical pattern on the masseters is highlighted. These assertions can easily be considered a contributing cause of the damage to the Temporomandibular Joint and, therefore, responsible for the 'Orofacial pain'.

Documents, reports and clinical evidence can be used to make the neurologist's assertion incompatible and the dentist's diagnostic conclusion compatible. To do this we must present some logical rules that describe the compatibility or incompatibility of the logic of classical language:

- A set of sentences , and a number of other phrases or statements are logically compatible if, and only if, the union between them is coherent.

- A set of sentences , and a number of other phrases or statements are logically incompatible if, and only if, the union between them is incoherent.

Let us try to follow this reasoning with practical examples:

The dentist colleague exposes the following sentence:

: Following the personalized techniques suggested by Xin Liang et al.[28] who focuses on the quantitative microstructural analysis of the fraction of the bone value, the trabecular number, the trabecular thickness and the trabecular separation on each slice of the CT scan of a TMJ, it appears that Mary Poppins is affected by Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) and the consequence causes Orofacial Pain.

At this point, however, the thesis must be confirmed with further clinical and laboratory tests, and in fact the colleague produces a series of assertions that should pass the compatibility filter as described above, namely:

Bone remodelling: The flattening of the axiographic traces highlighted in figure 5 indicates the joint remodelling of the right TMJ of Mary Poppins, such a report can be correlated to a series of researches and articles that confirm how malocclusion can be associated with morphological changes in the temporomandibular joints, particularly when combined with the age as the presence of a chronic malocclusion can worsen the picture of bone remodelling.[29] These scientific references determine the compatibility of the assertion.

Sensitivity and specificity of the axiographic measurement: A study was conducted to verify the sensitivity and specificity of the data collected from a group of patients affected by temporomandibular joint disorders with an ARCUSdigma axiographic system[30]; it confirmed a sensitivity of the 84.21% and a 92.86% sensitivity for the right and left TMJs respectively, and a specificity of 93.75% and 95.65%.[31] These scientific references determine compatibility of the assertion in the dental context precisely because of the consistency of related studies.[32]

Alteration of condylar paths: Urbano Santana-Mora and coll.[33] evaluated 24 adult patients suffering from severe chronic unilateral pain diagnosed as Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs). The following functional and dynamic factors were evaluated:

masticatory function;

remodelling of the TMJ or condylar pathway (CP); and lateral movement of the jaw or lateral guide (LG).

The CPs were assessed using conventional axiography and LG was assessed by using kinesiograph tracing[34]; Seventeen (71%) of the 24 (100%) patients consistently showed a side of habitual chewing side. The mean and standard deviation of the CP angles was 47.90 9.24) degrees. The average of LG angles was 42.9511.78 degrees.

Data collection emerged from the conception of a new TMD paradigm in which the affected side could be the usual chewing side, the side where the mandibular lateral kinematic angle was flatter. This parameter may also be compatible with the dental claim.

EMG Intereference pattern: M.O. Mazzetto and coll.[35] showed that the electromyographic activity of the anterior temporal muscles and the masseter was positively correlated with the "Craniomandibular index", indiced (CMI) with a and suggesting that the use of CMI to quantify the severity of TMDs and EMG to assess the masticatory muscle function, may be an important diagnostic and therapeutic elements. These scientific references determine compatibility of the assertion.

?

Obviously, the dentist colleague could endlessly keep on casting his statements, indefinitely.

Well, all of these statements seem coherent with the sentence initially described, whereby the dentist colleague feels justified in saying that the set of sentences , and a number of other assertions or clinical data are logically compatible as the union between them is coherent.«Following the logic of classical language, the dentist is right!»

(It would seem so! But, be careful, only in his own dental context!) |

This statement is so true that the could be infinitely extended, widened enough to obtain an that corresponds to it in an infinite significance, as long as it remains limited in its context; yet, without meaning anything from a clinical point of view in other contexts, like in the neurologist one, for instance.

Final considerations

From a perspective of observation of this kind, the Logic of Predicates can only fortify the dentist’s reasoning and, at the same time, strengthen the principle of the excluded third: the principle is strengthened through the compatibility of the additional assertions which grant the dentist a complete coherence in the diagnosis and in confirming the sentence : Poor Mary Poppins either has TMD, or she has not.«...and what if, with the advancement of research, new phenomena were discovered that would prove the neurologist right, instead of the dentist?»

|

Basically, given the compatibility of the assertions , coherently saying that Orofacial Pain is caused by a Temporomandibular Disorders could become incompatible if another series of assertions were shown to be coherent: this would make a different sentence compatible : could poor Mary Poppins suffer from Orofacial Pain from a neuromotor disorder (nOP) and not by a Temporomandibular Disorders?

In the current medical language logic, such assertions only remain assertions, because the convictions and opinions do not allow a consequent and quick change of the mindset.

Moreover, taking into account the risk that this change entails, in fact, we might consider a recent article on the epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders[36] in which the authors confirm that despite the methodological and population differences, pain in the temporomandibular region appears to be relatively common, occurring in about the 10% of the population; we may then objectively be led to hypothesize that our Mary Poppins can be included in the 10% of the patients mentioned in the epidemiological study, and contextually be classified as a patient suffering from Orofacial Pain from Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs).

In conclusion, it is evident that a classical logic of language, which has an extremely dichotomous approach (either it is white or it is black), cannot depict the many shades that occur in real clinical situations.

We need to find a more convenient and suitable language logic...«... can we then think of a Probabilistic Language Logic?»

(perhaps) |

- ↑ Stanley DE, Campos DG, «The logic of medical diagnosis», in Perspect Biol Med, 2013».

PMID:23974509

DOI:10.1353/pbm.2013.0019 - ↑ Croskerry P, «Adaptive expertise in medical decision making», in Med Teach, 2018».

PMID:30033794

DOI:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1484898 - ↑ Townsend GC, Brook AH, «The face, the future, and dental practice: how research in craniofacial biology will influence patient care», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24646132

DOI:10.1111/adj.12157 - ↑ Sperber GH, Sperber SM, «The genesis of craniofacial biology as a health science discipline», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24495071

DOI:10.1111/adj.12131 - ↑ Brook AH, Brook O'Donnell M, Hone A, Hart E, Hughes TE, Smith RN, Townsend GC, «General and craniofacial development are complex adaptive processes influenced by diversity», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24617813

DOI:10.1111/adj.12158 - ↑ Williams SD, Hughes TE, Adler CJ, Brook AH, Townsend GC, «Epigenetics: a new frontier in dentistry», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24611746

DOI:10.1111/adj.12155 - ↑ Yong R, Ranjitkar S, Townsend GC, Brook AH, Smith RN, Evans AR, Hughes TE, Lekkas D, «Dental phenomics: advancing genotype to phenotype correlations in craniofacial research», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24611797

DOI:10.1111/adj.12156 - ↑ Thesleff I, «Current understanding of the process of tooth formation: transfer from the laboratory to the clinic», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12102 - ↑ Peterkova R, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, «Three‐dimensional analysis of the early development of the dentition», in Aust Dent J, Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd on behalf of Australian Dental Association, 2014».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12130 - ↑ Lesot H, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Peterkova R, «Three‐dimensional analysis of molar development in the mouse from the cap to bell stage», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12132 - ↑ Hughes TE, Townsend GC, Pinkerton SK, Bockmann MR, Seow WK, Brook AH, Richards LC, Mihailidis S, Ranjitkar S, Lekkas D, «The teeth and faces of twins: providing insights into dentofacial development and oral health for practising oral health professionals», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12101 - ↑ Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, «Stem cells, tissue engineering and periodontal regeneration», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12100 - ↑ {{Cite book | autore = Brook AH | autore2 = Jernvall J | autore3 = Smith RN | autore4 = Hughes TE | autore5 = Townsend GC | titolo = The Dentition: The Outcomes of Morphogenesis Leading to Variations of Tooth Number, Size and Shape | url = https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/adj.12160 | volume = | opera = Aust Dent J | anno = 2014 | editore = | città = | ISBN = | PMID = | PMCID = | DOI = 10.1111/adj.12160 | oaf = | LCCN = | OCLC =

- ↑ Seow WK, «Developmental defects of enamel and dentine: challenges for basic science research and clinical management», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

PMID:24164394

DOI:10.1111/adj.12104 - ↑ Kieser JA, Farland MG, Jack H, Farella M, Wang Y, Rohrle O, «The role of oral soft tissues in swallowing function: what can tongue pressure tell us?», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12103 - ↑ Slavkin HC, «Research on Craniofacial Genetics and Developmental Biology: Implications for the Future of Academic Dentistry», in J Dent Educ, 1983».

PMID:6573384 - ↑ Slavkin HC, «The Future of Research in Craniofacial Biology and What This Will Mean for Oral Health Professional Education and Clinical Practice», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

PMID:24433547

DOI:10.1111/adj.12105 - ↑

Littlewood SJ, Kandasamy S, Huang G, «Retention and relapse in clinical practice», in Aust Dent J, 2017».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12475 - ↑ Miamoto CB, Silva Marques L, Abreu LG, Paiva SM, «Impact of two early treatment protocols for anterior dental crossbite on children’s quality of life», in Dental Press J Orthod, 2018».

- ↑ Alachioti XS, Dimopoulou E, Vlasakidou A, Athanasiou AE, «Amelogenesis imperfecta and anterior open bite: Etiological, classification, clinical and management interrelationships», in J Orthod Sci, 2014».

DOI:10.4103/2278-0203.127547 - ↑ Mizrahi E, «A review of anterior open bite», in Br J Orthod, 1978».

PMID:284793

DOI:10.1179/bjo.5.1.21 - ↑ For the sake of simplicity of exposition and reading, we will deal in this chapter with the symbol of belonging, the symbol of consequence and the "such that" as if they were quantifiers and connectives of propositions in classical logic.

Strictly speaking, within classical logic they should not be treated as such, but even if we do, this does not absolutely change the meaning of the speech and no inconsistencies of any kind are created. - ↑ Pereira LM, Pinto AM, «Reductio ad Absurdum Argumentation in Normal Logic Programs», Arg NMR, 2007, Tempe, Arizona - Caparica, Portugal – in «Argumentation and Non-Monotonic Reasoning - An LPNMR Workshop».

- ↑ Castroflorio T, Talpone F, Deregibus A, Piancino MG, Bracco P, «Effects of a Functional Appliance on Masticatory Muscles of Young Adults Suffering From Muscle-Related Temporomandibular Disorder», in J Oral Rehabil, 2004».

PMID:15189308

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01274.x - ↑ Maeda N, Kodama N, Manda Y, Kawakami S, Oki K, Minagi S, «Characteristics of Grouped Discharge Waveforms Observed in Long-term Masseter Muscle Electromyographic Recording: A Preliminary Study», in Acta Med Okayama, Okayama University Medical School, 2019, Okayama, Japan».

PMID:31439959

DOI:10.18926/AMO/56938 - ↑ Rudy TE, «Psychophysiological Assessment in Chronic Orofacial Pain», in Anesth Prog, American Dental Society of Anesthesiology, 1990».

ISSN: 0003-3006/90

PMID:2085203 - PMCID:PMC2190318 - ↑ Woźniak K, Piątkowska D, Lipski M, Mehr K, «Surface electromyography in orthodontics - a literature review», in Med Sci Monit, 2013».

e-ISSN: 1643-3750

PMID:23722255 - PMCID:PMC3673808

DOI:10.12659/MSM.883927 - ↑ Liang X, Liu S, Qu X, Wang Z, Zheng J, Xie X, Ma G, Zhang Z, Ma X, «Evaluation of Trabecular Structure Changes in Osteoarthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint With Cone Beam Computed Tomography Imaging», in Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2017».

PMID:28732700

DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2017.05.514 - ↑ Solberg WK, Bibb CA, Nordström BB, Hansson TL, «Malocclusion Associated With Temporomandibular Joint Changes in Young Adults at Autopsy», in Am J Orthod, 1986».

PMID:3457531

DOI:10.1016/0002-9416(86)90055-2 - ↑ KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach / Ris

- ↑ Kobs G, Didziulyte A, Kirlys R, Stacevicius M, «Reliability of ARCUSdigma (KaVo) in Diagnosing Temporomandibular Joint Pathology», in Stomatologija, 2007».

PMID:17637527 - ↑ Piancino MG, Roberi L, Frongia G, Reverdito M, Slavicek R, Bracco P, «Computerized axiography in TMD patients before and after therapy with 'function generating bites'», in J Oral Rehabil, 2008».

PMID:18197841

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01815.x - ↑ López-Cedrún J, Santana-Mora U, Pombo M, Pérez Del Palomar A, Alonso De la Peña V, Mora MJ, Santana U, «Jaw Biodynamic Data for 24 Patients With Chronic Unilateral Temporomandibular Disorder», in Sci Data, 2017».

PMID:29112190 - PMCID:PMC5674825

DOI:10.1038/sdata.2017.168

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Myotronics Inc., Kent, WA, US

- ↑ Oliveira Mazzetto M, Almeida Rodrigues C, Valencise Magri L, Oliveira Melchior M, Paiva G, «Severity of TMD Related to Age, Sex and Electromyographic Analysis», in Braz Dent J, 2014».

DOI:10.1590/0103-6440201302310 - ↑ LeResche L, «Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors», in Crit Rev Oral Biol Med, 1997».

PMID:9260045

DOI:10.1177/10454411970080030401

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system