6° Clinical case: Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy

In this section of Masticationpedia 'Are we sure to know everything?' we present two emblematic clinical cases that demonstrate the complexity and contextually the difficulty in making a differential diagnosis between orofacial disorders and serious organic pathologies. These diagnostic difficulties and limits do not only concern the operator's clinical ability, rather the operator's forma mentis too concentrated on pre-established axioms and dogmas. In this chapter we will present a clinical case of a patient who came to our attention from the Gastroenterology department due to a state of organic food wasting that was difficult to explain in the gastrointestinal tract. The young patient (aged 40) had undergone maxillofacial surgery for a unilateral crossbite some years before she came to our attention. Once the first trigeminal electrophysiological tests were performed, our pre-diagnosis of organic neuromotor damage was concluded and the patient was immediately referred to the trigeminal neurology and neurophysiopathology departments. The definitive diagnosis was 'Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy' trigeminal degenerative neuropathy signed 'FOSMN'.

Those working in centers specializing in orofacial pain or headache should be aware that a patient who initially experiences sensory disturbances on only one side may later manifest bilateral trigeminal neuropathy. Therefore, they should refer patients who begin to experience contralateral sensory symptoms for detailed diagnostic investigations. While no therapy is currently effective, early diagnosis would inform the patient of the outcome and rule out other possibly treatable causes.

Introduction

In this section of Masticationpedia 'Are we sure to know everything?' we present two emblematic clinical cases that demonstrate the complexity and contextually the difficulty in making a differential diagnosis between Orofacial disorders and serious organic pathologies. These diagnostic difficulties and limits do not only concern the operator's clinical ability, rather the operator's forma mentis too concentrated on pre-established axioms and dogmas. We have already mentioned the ambiguity and vagueness of verbal language logic but we should also be self-critical about established dogmas such as RDC/TMD protocols, P-value,[1] false positives,[2] false negatives and fallacies dictated by specialist contexts etc., so that our infinite clinical intuitive power is amplified and not dampened by easy access to automated machine learning models. This is so true that in an article by Naglaa El-Wakeel,[3] conducted on questionnaires on 151 dentistry professors from Egyptian government and private universities, it emerges that the percentage of diagnostic errors has been estimated to be < 20% and 20-40% of over 90% of the participants. The most commonly misdiagnosed conditions were oral mucosal lesions (83.4%), followed by temporomandibular and periodontal joint conditions (58.9%). The conclusion was that the main causes of this problem are the dental education system and the lack of adequate training. Just a recent report by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine highlighted a number of shortcomings, particularly in the training of TMDs in dental schools in the United States of America at both the pre-doctoral and post-doctoral (dental) levels, as well as the need to address historical inconsistencies in both diagnosis and treatment. Recently, the American Dental Association recognized orofacial pain as a specialty, which should increase the level and availability of expertise in treating these problems. The article concludes by noting that based on the best current evidence. This report is an attempt to alert the profession to stop irreversible and invasive therapies for the vast majority of TMDs and to recognize that most of these disorders are amenable to conservative and reversible interventions.[4]

Clinical analysis

Patient who came to our attention from the Gastroenterology department due to a state of organic food wasting that was difficult to explain in the gastrointestinal diseases. The young patient (aged 40) to whom we give our usual invented name 'Flora' (name of the goddess of flowers in ancient Rome) had undergone maxillofacial surgery for a unilateral crossbite 5 years before she reached our attention. 'Flora' had never had any sensitivity disorder but only an aesthetic problem in smiling and minor masticatory problems such as to turn to a maxillofacial surgeon. The surgery consisted of a rapid surgical palate expansion but after an unquantified period of time there was a recurrence and at the same time slight forms of facial tingling especially in the upper perioral area together with an unexplained gingival recession of the right maxillary dental arch. A few months later, small skin vesicles began to form in her right perioral area, interpreted at the time as a vasculitis manifestation. (Figure 1) Our Flora obviously worried about these consequences relied on dental care both for gum recessions but also for psychological support given the relapses resolved palliatively with a biteplane with the intention of managing night-time stress. Over a period of another 10 months, the patient worried about the conspicuous worsening of her psychophysical conditions and excessive weight loss, decided to refer to a gastroenteric expert who excluded any gastrointestinal pathological form or attributable to malabsorption. (Figure 2) The gastroenterologist colleague had the intuition that perhaps the clinical manifestations of the patient Flora could be attributable to a masticatory difficulty and reported it to our 'Neurognathology' Centre.

Our first approach, for those who have already followed the Masticationpedia diagnostic process, consisted of a quick classic gnathological analysis to which we gave a minimum specific weight given, clearly, the neuropsychophysical conditions in which the patient presented and therefore we bypassed the analysis of assertions in the dental context to immediately perform trigeminal electrophysiological tests.

At the first approach by performing the jaw jerk we realized the seriousness of the clinical situation. The absence of the reflex on the right masseter concomitant with the recession of the right maxillary hemiarch and the skin vesicles gave rise to an important doubt: if we had wanted to attribute the locally performed operation on the maxilla to the intervention, we would have had to expect an electrophysiological deficit attributable to the trigeminal area V2 and not V3 because V2 does not affect the motor responses of the jaw jerk. (Figure 3)

For this reason we have deepened the examination also performing the mechanical silent period of the masseters. (figure 4) The result was striking and confirms the organic damage due to the absence of the jaw jerk and contextually the decrease in duration of the silent period. Already these first two tests directed the pre-diagnosis to an organic/structural damage of the trigeminal nervous system, therefore, a further electrophysiological study of the clinical case was excluded and the patient was immediately directed to the neurophysiology departments.

The ' Demarcation' model was also bypassed so as not to waste further time, but we quickly performed an analysis to look for a more specific morbid form to approach the pre-diagnosis of organic damage. For this reason, the model of the Cognitive Neural Network (CNN) detailed in the previous chapters:

(...... pay attention to the initialization term and the order in which the 'queries' follow one another)

Cognitive Neural Network

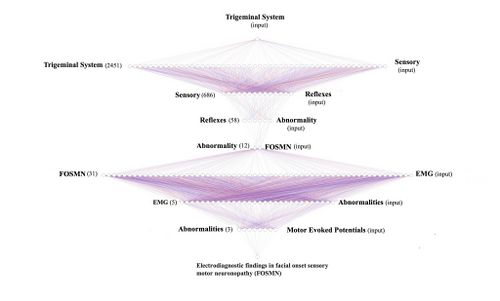

From what emerges from the neurological statements, the 'State' of the Trigeminal Nervous System appears unstructured, highlighting anomalies of the trigeminal reflexes, therefore, the 'Initialization' command is the 'Trigeminal System'to go and test the database (Pubmed).

- 1st loop open: The 'Initialization' command 'Trigeminal System', therefore, is considered as initial input for the Pubmed database which responds with 2,452 clinical/experimental data available to the clinician. The opening of the first true cognitive analysis is elaborated precisely on the analysis of the first result of the 'RNC' corresponding to ' Trigeminal System'. At this stage we realize that the reported datasets include a wide variety of subsets. For this reason we must always remain very generic and insert a corresponding key with an equally broad response that includes one of the signs and/or symptoms found in the anamnesis and clinical analysis. In this case the sensory disturbance reported by the patient will be the second query to be inserted into the network.

- 2st loop open: The 'Sensory' key returns 666 articles on which to do cognitive brainstorming and that is to think about which other element should be inserted in order not to deviate the search from the pre-established set. For example, if in this stage we had entered the term 'jaw jerk' (which has emerged as a decisive test for the diagnosis) the network returns only one article (Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Neuropathic Orofacial Pain: Role of Clinical Neurophysiology). This article concerns a series of tests that can be used for the differential diagnosis in neuropathies but does not help us in researching the type of structural damage the patient is affected by. For this reason it is best to stick to a broad perspective of generic information such as 'Reflexes'.

- 3st loop open: Always bearing in mind that we are still in the starting set (Trigeminal System) the term ' Reflexes' returns 58 scientific articles on which to continue to do cognitive brainstorming (CBing), but how? CBing consists of a dynamic intellectual analysis of the healthcare operator who, knowing the clinical complexity of the clinical case, manages to direct the search for the necessary information by extricating himself from the myriad of database connections that can lead to a dead end, in a sort of node that loses most of the specific information. This CBing is to narrow down to a few articles best related to our clinical case 'Flora'. The generic procedure could be to verify how many articles respond to several terms of clinical question in the same 3rd open loop quantifying their number and value in the context to then better choose the term to insert in the '4st loop closed' which would in fact close the first series of the RCN'. An example could be the following:

- Sensory: searching the text for the term 'Sensory' we will have 10 articles

- Motor: searching the text for the term 'Motor' we will have 6 articles

- Abnormal:searching the text for the term 'Abnormal' we will have only 3 articles on which to dwell to consider the second step of the 'RNC'. The three articles below are very specific in identifying the most suitable path to follow. Details are in the caption. We could have stopped here but the definitive diagnosis is also an important step for the colleagues who will take charge of our patient.

- Therefore the first section of the 'RCN' will conclude with the term 'Abnormality.

- Cognitive Brainstorming su terzo loop open:

Article 3: This article is superimposable on our pre-diagnosis and reports signs and symptoms very similar to our patient, so it is considered as corresponding information and therefore a path to follow. The next step, therefore, will concern the 'Sensory and motor neuronopathy with facial onset' initialed as 'FOSMN'.

- 4st loop closed: The term 'Abnormality'reduces the search to 12 articles which will also be subjected to detailed CBing from which a clinical manifestation very close to the psychophysical state of our patient 'Flora' is extrapolated, a disease coined with the acronym FOSMN which stands for ' Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy'.

- 5st loop open: As stated, we are inserting in the database no longer a term but an acronym 'FOSMN' which corresponds to 'Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy'. The database returns 31 articles on which to process further requests. Up to now we have used generic terms in order not to lose the connection between nodes but now we need to go into more detail and insert terms that have been highlighted in the clinical and laboratory analysis such as, for example, electromyographic anomalies for which we insert the term 'EMG' .

- 6st loop open: The term 'EMG' drastically reduces the CBing to only 5 items to be carefully weighed to continue with the 'RNC' and since a serious EMG abnormality of amplitude and duration was highlighted in our 'Flora' we insert the term 'Abnormalities' in the database.

- 7st loop open: Of the three articles on the term'Abnormalities' he replies with returning 3 articles and we preferred to insert a more specific and advanced term of scientific studies, the 'motor evoked potentials' since this pathology is a sensory and motor clinical manifestation.

- 8st loop open: By inserting the term 'motor evoked potentials' in the database we have reached a conclusion point the typical 'Loop closed' that returns the article 'Electrodiagnostic findings in facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy (FOSMN)'.

- 9st loop closed: As we have seen, the 'RNC' is a cognitive network model that helps the clinician to unravel the diagnostic complexity by searching, precisely, with a human cognitive dynamic and not machine learning, for a possible overlap of clinical elements as well as decrypting the encrypted signal sent out by the body. As we have verified, in fact, specifically in the cases of Mary Poppins and 'Bruxer'. However, of the 2452 articles of the set identified with the initialization world we arrived with only 8 loops to extract only one article 'Electrodiagnostic findings in facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy (FOSMN)'' on which to do further brainstorming.

Final diagnosis

The patient 'Flora' was, therefore, immediately referred to the trigeminal neurophysiology departments with a pre-diagnosis of 'Electrodiagnostic findings in facial onset sensory motor neuronopathy (FOSMN)' and we report the procedure that confirmed the diagnosis to make it more the diagnostic path that a clinical dentist should follow in such rare but dramatically serious cases is explanatory. In fact, the diagnosis is not linear in the first cases because the symptoms could be superimposed on various physiopathogenetic phenomena such as temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), trigeminal neuralgia (TN), forms of trigeminal neuropathies such as 'isolated sensory trigeminal neuropathy' (TISN ) and that identified in this clinical case 'Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy' (FOSMN). This diagnostic process is required because in the case of TISN or FOSMN the prognosis is often poor.

In Prof. Cruccu's Department of Neurology and Clinical Neurophysiology, the patient underwent the following tests:

Clinical and laboratory investigations

È stata valutata la funzione sensoriale trigeminale ed extra-trigeminale: il tatto è stato studiato con un batuffolo di cotone, la vibrazione con un diapason (128 Hz) e la sensazione di puntura di spillo con un bastoncino da cocktail di legno. La compromissione dell'andatura e la forza muscolare sono state valutate con il punteggio del Medical Research Council. E' stato anche chiesto di segnalare sintomi disautonomici. La paziente è stata sottoposta a test di laboratorio, inclusi test per escludere cause identificabili di neuropatia del trigemino: saggi di autoanticorpi per rilevare la malattia del tessuto connettivo (anticorpi antinucleari, anti-DNA a doppia elica, antigeni estraibili antinucleari, inclusi anti Sm, anti RNP, anti Scl70 e anti -fosfolipidi, anticorpi citoplasmatici antineutrofili e anti Ro/SSA e anti-La/SSB per la malattia di Sjögren).

Sono stati eseguiti anche il test genetico sierico per la malattia di Kennedy, agli esteri del colesterolo e al basso colesterolo sierico per la malattia di Tangeri, all'accumulo di glicosfingolipidi per la malattia di Fabry e all'enzima di conversione dell'angiotensina sierica per la neurosarcoidosi. E' stata eseguita, ovviamente, anche la risonanza magnetica (MRI) potenziata con gadolinio del cervello e del midollo spinale.

Le biopsie del nervo sopraorbitario sono state eseguite da un chirurgo plastico esperto. Campioni fissati con glutaraldeide al 2% in soluzione salina tamponata con fosfato (PBS) a 4°C. I campioni sono stati post-fissati in tetrossido di osmio all'1% in tampone veronal acetato (pH 7,4) per 1 ora a 25°C, colorati con acetato di uranile (5 mg/ml) per 1 ora a 25°C, disidratati in acetone e incorporati in Epon 812 (EMbed 812, Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA, USA).

Le sezioni semisottili sono state colorate con blu di toluidina per la valutazione al microscopio ottico. Sezioni ultrasottili da blocchi di tessuto con il corretto orientamento, post-colorate con acetato di uranile e idrossido di piombo, sono state esaminate con un microscopio elettronico a trasmissione Morgagni 268D (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA). Le immagini digitali sono state analizzate con il software AnalySIS (SIS) e tutte le strutture mielinizzate e non mielinizzate sono state identificate e misurate. Le densità delle fibre sono state calcolate ed espresse come numero medio di fibre/mm2.

Neurofisiologici trigeminali

Sono stati testati i potenziali evocati motori del trigemino attraverso stimolazione magnetica transcranica,[5] il riflesso temporale H, valutando la fibra Aα (fibra Ia) nel riflesso trigemino monosinaptico,[6] i primi componenti del riflesso ammiccante (R1) dopo la stimolazione elettrica del nervo sopraorbitale e il riflesso inibitorio del massetere (SP1) dopo la stimolazione del nervo mentale, valutando le fibre .[7] Si è registrato, anche, i potenziali evocati dal laser (LEP) per studiare i nocicettori (-LEP) e i recettori del calore da fibre amieliniche (C-LEP).[8]

I test neurofisiologici hanno aderito ai requisiti tecnici emessi dalla International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology.[9][10]

Risultati significativi delle indagini

I potenziali evocati motori da stimolazione transcraniale magnetica e il riflesso H del muscolo temporale hanno prodotto risultati normali; al contrario, le registrazioni del riflessi hanno mostrato gravi anomalie: la prima risposta a diventare assente bilateralmente è stata il riflesso inibitorio del massetere precoce (SP1) dopo la stimolazione del nervo mentale. Il riflesso di ammiccamento precoce (R1). Mentre i LEP mediati dalle fibre erano spesso anormali (ma meno compromessi rispetto ai primi riflessi trigeminali), i C-LEP, mediati dalle fibre C amieliniche erano normali. Questi modelli di anomalie neurofisiologiche in generale suggerivano che la malattia progredisse dalle fibre afferenti più grandi a quelle più piccole.

L'unica eccezione degna di nota era il normale riflesso temporale H mediato dall'afferenza . Sia la microscopia ottica che quella elettronica hanno mostrato solo una degenerazione simil-walleriana che coinvolge le fibre mieliniche, più grave per il gruppo delle grandi e piccole, con nessun cambiamento infiammatorio.

Discussione

Dallo studio di Cruccu et al. [11]si evince innanzitutto che nonostante dettagliate indagini neurofisiologiche e morfometriche, non si possono riscontrare differenze cliniche, neurofisiologiche o neuropatologiche tra TISN e FOSMN, quindi, le due malattie potrebbero essere neuropatie patofisiologicamente simili del tipo di neuropatie dissociate che risparmiano completamente le fibre amieliniche così dimostrato dall'esame bioptico. La microscopia ottica ed elettronica in campioni di biopsia del nervo sopraorbitario da pazienti con TISN e quelli con FOSMN ha mostrato una perdita di fibre mieliniche assonali variamente grave, come altri hanno riportato in questi pazienti. [12][13] Estendiamo questi risultati fornendo dati quantitativi che mostrano che la neuropatia del trigemino colpisce le fibre in modo più grave rispetto alle fibre . La prova che il danno alle fibre nervose progredisce dalla fibra più grande a quella più piccola proviene anche dai risultati neurofisiologici, che mostrano invariabilmente risposte mediate dalla fibra compromessa anche nelle prime fasi della malattia. Al contrario, le risposte mediate dalla fibra erano molto meno compromesse.

Secondo Cruccu et al.[11] il risparmio temporale del riflesso H fornisce la prova che la FOSMN colpisce principalmente i corpi cellulari.[13][14]Una neuropatia dissociata che colpisce progressivamente le fibre mielinizzate più grandi e poi quelle più piccole dovrebbe in teoria alterare gravemente un riflesso mediato dalle afferenze Aα dai fusi muscolari. Al contrario, risparmia le afferenze primarie dai fusi del muscolo trigemino perché viaggiano nel motore piuttosto che nella radice sensoriale. Altrettanto importante, piuttosto che giacere nel ganglio sensoriale, i loro corpi cellulari giacciono nel nucleo del trigemino mesencefalico.[15][16] Questa caratteristica anatomica unica spiega anche perché lo scatto del tendine mandibolare (o scatto della mandibola) viene risparmiato in altre due neuropatie del trigemino: la sindrome di Sjögren e la malattia di Kennedy.[17][18]

A differenza degli studi precedenti che utilizzavano un martello riflesso tenuto in mano per suscitare lo scatto del tendine mandibolare, abbiamo utilizzato il riflesso temporale H per evitare possibili interferenze da disfunzione temporomandibolare o malocclusione, condizioni che possono indurre anomalie o addirittura una risposta riflessa assente al riflesso tenuto in mano martello.[19]

Sorge un dubbio Amletico:

Questo dato è di essenziale importanza per il modello scientifico clinico proposto dal gruppo di Masticationpedia quello della 'Indeterminazione Probabilistica' nei sistemi complessi organici, per cui gli esami di laboratorio, in molti casi, potrebbero evidenziare anomalie altrimenti occultate e che si sarebbero evidenziate con lunghe latenze temporali e gravi ripercussioni cliniche. In particolare visto i risultati fisopatogenetici emersi dal lavoro di Cruccu[11] e nello specifico nella nostra paziente 'Flora', significa che i risultati anomali evidenziati nel nostro periodo di pre-diagnosi nella paziente ( jaw jerk e silent period) erano una manifestazione clinica anormale già presente ancor prima che la malattia si fosse diffusa ulteriormente alle fibre mieliniche di più piccolo calibro. In poche parole la parestesia riferita dalla paziente era patognomonica di danno delle fibre mieliniche dopo un processo di destrutturazione dei nuclei mesencefali e del danno alle fibre .

Rimane, però, un dubbio ancor più complesso da sciogliere:

Se il danno organico riguarda le strutture nervose motorie con una progressione dalle fibre alle fibre con conseguente danno strutturale dei nuclei motori mesencefali risparmiando inizialmente le fibre di piccolo calibro amieliniche e l'intervento di ortognatica fu eseguito soltanto nel mascellare come si spiega l'inizializzazione della malattia manifestatasi principalmente nell'area V3 trigmeinale?

(.......siamo sicuri, allora, di sapere tutto?)

- ↑ S Catarzi, D Morrone, D Ambrogetti, P Bravetti, M Rosselli Del Turco, S Ciatto[Errors in mammography. II. False positives] Radiol Med. 1992 Mar;83(3):201-5.

- ↑ D Morrone 1, D Ambrogetti, P Bravetti, S Catarzi, S Ciatto, M Rosselli del Turco[Diagnostic errors in mammography. I. False negative results]. Radiol Med.1991 Sep;82(3):212-7.

- ↑ El-Wakeel N, Ezzeldin N. Diagnostic errors in Dentistry, opinions of egyptian dental teaching staff, a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2022 Dec 20;22(1):621. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02565-9.PMID: 36539763

- ↑ Gary D Klasser, Elliot Abt, Robert J Weyant, Charles S Greene. Temporomandibular disorders: current status of research, education, policies, and its impact on clinicians in the United States of America. Quintessence. 2023 Apr 11;54(4):328-334.doi: 10.3290/j.qi.b3999673.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Berardelli A, Inghilleri M, Manfredi M. Functional organization of the trigeminal motor system in man. A neurophysiological study. Brain. 1989;112:1333–1350. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.5.1333.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Truini A, Priori A. Excitability of the human trigeminal motoneuronal pool and interactions with other brainstem reflex pathways. J Physiol. 2001;531:559–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0559i.x.

- ↑ Valls-Solé J. Neurophysiological assessment of trigeminal nerve reflexes in disorders of central and peripheral nervous system. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:2255–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.04.020.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Pennisi E, Truini A, Iannetti GD, Romaniello A, Le Pera D, De Armas L, Leandri M, Manfredi M, Valeriani M. Unmyelinated trigeminal pathways as assessed by laser stimuli in humans. Brain. 2003;126:2246–2256. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg227.

- ↑ Kimura J, editor. Peripheral Nerve Diseases, Handbook of Clinical Neurophysiology.Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Aminoff MJ, Curio G, Guerit JM, Kakigi R, Mauguiere F, Rossini PM, Treede RD, Garcia-Larrea L. Recommendations for the clinical use of somatosensory-evoked potentials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1705–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Cruccu G, Pennisi EM, Antonini G, Biasiotta A, di Stefano G, La Cesa S, Leone C, Raffa S, Sommer C, Truini A.Trigeminal isolated sensory neuropathy (TISN) and FOSMN syndrome: despite a dissimilar disease course do they share common pathophysiological mechanisms? BMC Neurol. 2014 Dec 19;14:248. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0248-2.PMID: 25527047

- ↑ Lecky BR, Hughes RA, Murray NM. Trigeminal sensory neuropathy. A study of 22 cases. Brain. 1987;110:1463–1485. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.6.1463.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Vucic S, Tian D, Chong PS, Cudkowicz ME, Hedley-Whyte ET, Cros D. Facial onset sensory and motor neuronopathy (FOSMN syndrome): a novel syndrome in neurology. Brain. 2006;129:3384–3390. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl258.

- ↑ Vucic S1, Stein TD, Hedley-Whyte ET, Reddel SR, Tisch S, Kotschet K, Cros D, Kiernan MC. FOSMN syndrome: novel insight into disease pathophysiology. Neurology. 2012;79:73–79. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825dce13.

- ↑ Collier TG, Lund JP. The effect of sectioning the trigeminal sensory root on the periodontally-induced jaw-opening reflex. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1533–1537. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660100401.

- ↑ Dessem D, Taylor A. Morphology of jaw-muscle spindle afferents in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;282:389–403. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820306.

- ↑ Valls-Sole J, Graus F, Font J, Pou A, Tolosa ES. Normal proprioceptive trigeminal afferents in patients with Sjögren's syndrome and sensory neuronopathy. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:786–790. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280609.

- ↑ Antonini G, Gragnani F, Romaniello A, Pennisi EM, Morino S, Ceschin V, Santoro L, Cruccu G: Sensory involvement in spinal-bulbar muscular atrophy (Kennedy's disease).Muscle Nerve 2000; 23:252-258.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Iannetti GD, Marx JJ, Thoemke F, Truini A, Fitzek S, Galeotti F, Urban PP, Romaniello A, Stoeter P, Manfredi M, Hopf HC. Brainstem reflex circuits revisited. Brain. 2005;128:386–394. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh366.