Difference between revisions of "2° Clinical case: Pineal Cavernoma"

(Created page with "alt=|left|200x200px Few studies have attempted to characterize the pain associated with bruxism (i.e., to examine the neurobiological and physiological characteristics of the mandibular muscles). Some clinical cases and small-scale studies suggest that certain drugs linked to the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and adrenergic systems can either suppress or exacerbate bruxism. Further, the majority of these pharmacological studies indicate that vari...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Bruxer SP2 .jpg | [[File:Bruxer SP2.jpg|left|200x200px]] | ||

Few studies have attempted to characterize the pain associated with bruxism (i.e., to examine the neurobiological and physiological characteristics of the mandibular muscles). Some clinical cases and small-scale studies suggest that certain drugs linked to the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and adrenergic systems can either suppress or exacerbate bruxism. Further, the majority of these pharmacological studies indicate that various classes of drugs can influence the muscular activity related to bruxism, without exerting any effect on OP. Therefore, the sensitization of the trigeminal nociceptive system and the facilitating effect on mandibular stretch reflexes and CNS hyperexcitability are neurophysiopathogenetic phenomena that can be correlated to pain in the craniofacial region. However, up to now, no correlation has been reported between OP, dysfunction of the mesencephalic nuclei, and facilitation of trigeminal nociception, except for a clinical study on a patient affected by pontine cavernoma, which highlighted a relative facilitation of the trigeminal nociceptive system through the blink reflex. | |||

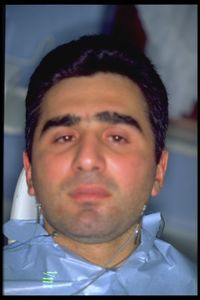

As anticipated we will take up the same diagnostic language presented for the patient Mary Poppins so that it becomes an assimilable and practicable model, and we will try to superimpose it on the present clinical case called 'Bruxer'. The subject was a 32-year-old man suffering from pronounced nocturnal and diurnal bruxism and chronic bilateral OP prevalent in the temporoparietal regions, with greater intensity and frequency on the left side. Neurological examination showed a contraction of the masseter muscles with pronounced stiffness of the jaw, diplopia and loss of visual acuity in the left eye, left gaze nystagmus with a rotary component, papillae with blurred borders and positive bilateral Babynski's, and polykinetic tendon reflexes in all four limbs. | |||

=== Introduction === | |||

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24165294/ | |||

As anticipated in the chapter '[[Bruxism - en|Bruxism]]' we will avoid indicating this disorder as an exclusive dental correlate and will seek a broader and essentially more neurophysiological description by making a brief excursus on dystonic phenomena, on 'Orofacial Pain' and only then will we consider the phenomenon 'bruxism' true and own. Subsequently we will move on to the presentation of the clinical case. | |||

[[File:IMG0103.jpg|thumb|300x300px|'''Figura 1:''' The subject was a 32-year-old man suffering from pronounced nocturnal and diurnal bruxism and chronic bilateral Oorofacial pain ]]Dystonia is an involuntary, repetitive, sustained (tonic), or spasmodic (rapid or clonic) muscle contraction. The spectrum of dystonias can involve various regions of the body. Of interest to oral and maxillofacial surgeons are the cranial-cervical dystonias, in particular, orofacial dystonia (OFD). OFD is an involuntary, sustained contraction of the periorbital, facial, oromandibular, pharyngeal, laryngeal, or cervical muscles.<ref>Thompson PD, Obeso JA, Delgado G, Gallego J, Marsden CD. Focal dystonia of the jaw and differential diagnosis of unilateral jaw and masticatory spasm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:651–656. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.6.651. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar][Ref list]</ref> OFD can involve the masticatory, lower facial, and tongue muscles, which may result in trismus, bruxism, involuntary jaw opening or closure, and involuntary tongue movement. | |||

The etiology of OFD is varied and includes genetic predisposition, injury to the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral trauma, medications, metabolic or toxic states, and neurodegenerative disease. However, in the majority of patients, no specific cause can be identified. An association was found among painful temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), migraine, tension-type headache, and sleep bruxism, although the association was only significant for chronic migraine. The association between painful TMDs and sleep bruxism significantly increased the risk for chronic migraine, followed by episodic migraine and episodic tension-type headache.<ref>Fernandes G, Franco AL, Gonçalves DA, Speciali JG, Bigal ME, Camparis CM. Temporomandibular disorders, sleep bruxism, and primary headaches are mutually associated. J Orofac Pain. 2013;27(1):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> | The etiology of OFD is varied and includes genetic predisposition, injury to the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral trauma, medications, metabolic or toxic states, and neurodegenerative disease. However, in the majority of patients, no specific cause can be identified. An association was found among painful temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), migraine, tension-type headache, and sleep bruxism, although the association was only significant for chronic migraine. The association between painful TMDs and sleep bruxism significantly increased the risk for chronic migraine, followed by episodic migraine and episodic tension-type headache.<ref>Fernandes G, Franco AL, Gonçalves DA, Speciali JG, Bigal ME, Camparis CM. Temporomandibular disorders, sleep bruxism, and primary headaches are mutually associated. J Orofac Pain. 2013;27(1):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 18: | ||

Orofacial pain (OP), including pain from TMDs, exerts a modulatory effect on mandibular stretch reflexes.<ref>Dubner R, Ren K. Brainstem mechanisms of persistent pain following injury. J Orofac Pain. 2004;18(4):299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> Electrophysiological studies have shown that experimentally induced pain from injections of 5% hypertonic saline solution into the masseter muscle causes an increase in the peak-to-peak amplitude of the jaw jerk. This facilitatory effect appears to be related to an increased sensitivity of the fusimotor system, which at the same time causes muscle stiffness.<ref>Wang K, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Modulation of exteroceptive suppression periods in human jaw-closing muscles by local and remote experimental muscle pain. Pain. 1999;82(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00058-5.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar][Ref list]</ref> In addition, a number of animal studies of experimentally-induced muscle pain have shown that activation of the muscle nociceptors markedly influences the proprioceptive properties of the muscle spindles through a central neural pathway,<ref>Ro JY, Capra NF. Modulation of jaw muscle spindle afferent activity following intramuscular injections with hypertonic saline. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):117–127.[PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> and that washing of the local algogenic substance causes a return to normal tendon reflexes. | Orofacial pain (OP), including pain from TMDs, exerts a modulatory effect on mandibular stretch reflexes.<ref>Dubner R, Ren K. Brainstem mechanisms of persistent pain following injury. J Orofac Pain. 2004;18(4):299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> Electrophysiological studies have shown that experimentally induced pain from injections of 5% hypertonic saline solution into the masseter muscle causes an increase in the peak-to-peak amplitude of the jaw jerk. This facilitatory effect appears to be related to an increased sensitivity of the fusimotor system, which at the same time causes muscle stiffness.<ref>Wang K, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Modulation of exteroceptive suppression periods in human jaw-closing muscles by local and remote experimental muscle pain. Pain. 1999;82(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00058-5.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar][Ref list]</ref> In addition, a number of animal studies of experimentally-induced muscle pain have shown that activation of the muscle nociceptors markedly influences the proprioceptive properties of the muscle spindles through a central neural pathway,<ref>Ro JY, Capra NF. Modulation of jaw muscle spindle afferent activity following intramuscular injections with hypertonic saline. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):117–127.[PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> and that washing of the local algogenic substance causes a return to normal tendon reflexes. | ||

However, few studies have attempted to characterize the pain associated with bruxism (i.e., to examine the neurobiological and physiological characteristics of the mandibular muscles). Some clinical cases and small-scale studies suggest that certain drugs linked to the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and adrenergic systems can either suppress or exacerbate bruxism. Further, the majority of these pharmacological studies indicate that various classes of drugs can influence the muscular activity related to bruxism, without exerting any effect on OP.<ref>Winocur E, Gavish A, Voikovitch M, Emodi-Perlman A, Eli I. Drugs and bruxism: a critical review. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17(2):99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> | However, few studies have attempted to characterize the pain associated with bruxism (i.e., to examine the neurobiological and physiological characteristics of the mandibular muscles). Some clinical cases and small-scale studies suggest that certain drugs linked to the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and adrenergic systems can either suppress or exacerbate bruxism. Further, the majority of these pharmacological studies indicate that various classes of drugs can influence the muscular activity related to bruxism, without exerting any effect on OP.<ref>Winocur E, Gavish A, Voikovitch M, Emodi-Perlman A, Eli I. Drugs and bruxism: a critical review. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17(2):99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]</ref> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 24: | ||

==== Case report ==== | ==== Case report ==== | ||

As anticipated we will take up the same diagnostic language presented for the patient Mary Poppins so that it becomes an assimilable and practicable model, and we will try to superimpose it on the present clinical case called 'Bruxer'.<blockquote>The subject was a 32-year-old man suffering from pronounced nocturnal and diurnal bruxism and chronic bilateral OP prevalent in the temporoparietal regions, with greater intensity and frequency on the left side. Neurological examination showed a contraction of the masseter muscles with pronounced stiffness of the jaw, diplopia and loss of visual acuity in the left eye, left gaze nystagmus with a rotary component, papillae with blurred borders and positive bilateral Babynski’s, and polykinetic tendon reflexes in all four limbs.</blockquote> | |||

{{Q2|does the tennis match start again?| | |||

From what has been exposed in the previous chapters from the '[[Introduction/en|Introduction]]' to the chapters '[[Logic of medical language: Introduction to quantum-like probability in the masticatory system - en|Logic of medical language]]' and the last chapter '[[Bruxism - en|Bruxism]]', in addition to the complexity of the arguments and the vagueness of the verbal language, we could find ourselves faced with a clinical situation in which seems to dominate one of the contexts considered. | |||

{{Q2|does the tennis match start again?|it looks like it but....}} | |||

Unlike the patient with 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', the clinical case of our poor 'Bruxer' shows a phenomenon of overlapping of propositions, assertions and logical sentences in the dental and neurological context and apparently neither of the two obtains an absolute and clear compatibility and consistency. This has repercussions in the clinic in which all the actors involved (medical examiners) are right and contextually wrong, making the diagnostic conclusion inadequate and dangerous, but let's see the process as a whole step by step. | |||

==== | ==== Significance of contexts ==== | ||

Nel il '''contesto odontoiatrico''' avremo le seguenti frasi ed asserzioni a cui diamo un valore numerico per facilitare la trattazione e cioè <math>\delta_n=[0|1]</math> dove lo <math>\delta_n=0</math> indica 'normalità' e <math>\delta_n=1</math> 'anormalità e dunque positività del referto: | Nel il '''contesto odontoiatrico''' avremo le seguenti frasi ed asserzioni a cui diamo un valore numerico per facilitare la trattazione e cioè <math>\delta_n=[0|1]</math> dove lo <math>\delta_n=0</math> indica 'normalità' e <math>\delta_n=1</math> 'anormalità e dunque positività del referto: | ||

| Line 37: | Line 43: | ||

<math>\delta_4</math>Symmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5, <math>\delta_4 =0\longrightarrow</math> Normalità, negatività del referto | <math>\delta_4</math>Symmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5, <math>\delta_4 =0\longrightarrow</math> Normalità, negatività del referto | ||

<center><gallery widths="130" heights="200" perrow="5" slideshow""="" mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:SC-05-0011. | |||

File:SC-05-0021. | |||

File:SC-05-0020. | In the '''dental context''' we will have the following sentences and statements to which we give a numerical value to facilitate the treatment, namely <math>\delta_n=[0|1]</math> where it <math>\delta_n=0</math> indicates 'normal' e <math>\delta_n=1</math> abnormality and therefore positivity of the report: | ||

File:Bruxer EMG. | |||

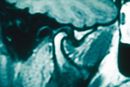

<math>\delta_1</math> Negative MR report of the TMJ in Figure 2, <math>\delta_1=0\longrightarrow</math>Normality, negativity of the report | |||

<math>\delta_2</math> Negative axiographic report for right condylar traces in Figure 3, <math>\delta_2=0\longrightarrow</math> Normality, negativity of the report | |||

<math>\delta_3</math> Negative axiographic report for left condylar traces in Figure 4, <math>\delta_3=0\longrightarrow</math> Normality, negativity of the report | |||

<math>\delta_4</math> Symmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5, <math>\delta_4 =0\longrightarrow</math> Normality, negativity of the report<center><gallery widths="130" heights="200" perrow="5" slideshow""="" mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:SC-05-0011.jpeg|'''Figura 2:''' <math>\delta_1=0\longrightarrow</math> Le immagini MR dell'articolazione temporomandibolare ( mostrato per semplificazione solo il lato destro) non mostra segni di deragliamento meniscale e/o di infiammazioni. Referto di conseguenza negativo. | |||

File:SC-05-0021.jpeg|'''Figura 3:''' <math>\delta_2=0\longrightarrow</math>Tracciato assiografico eseguito con cucchiaio paraocclusale che mostra un normale andamento traslatorio e mediotrusivo del condilo destro. Referto di conseguenza negativo | |||

File:SC-05-0020.jpeg|'''Figura 4:''' <math>\delta_3=0\longrightarrow</math> Tracciato assiografico eseguito con cucchiaio paraocclusale che mostra un normale andamento traslatorio e mediotrusivo del condilo sinistro | |||

File:Bruxer EMG.jpeg|'''Figura 4:''' <math>\delta_4=0\longrightarrow</math>Tracciato EMG muscoli masseteri ( superiore/ massetere destro e sinistro rispettivamente). Il test mostra simmetria bilaterale nel reclutamento unità motorie | |||

</gallery></center> | </gallery></center> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 75: | ||

<center><gallery widths="250" heights="200" perrow="3" slideshow""="" mode="slideshow"> | <center><gallery widths="250" heights="200" perrow="3" slideshow""="" mode="slideshow"> | ||

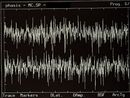

File:Bruxer MEP. | File:Bruxer MEP.jpeg|'''Figura 5:''' <math>{\gamma _{1}}=</math> Potenziali Evocati Motori delle radici trigeminali | ||

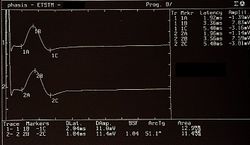

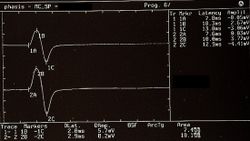

File:Bruxer Jaw jerk. | File:Bruxer Jaw jerk.jpeg|'''Figure 6:''' <math>{\gamma _{2}}=</math> Jaw jerk rilevato elettrofisiologicamente sui masseteri destro (tracce superiori) e sinistro (tracce inferiori). La morfologia e durata dei periodi silenti denominati 'Esteroceptive Suppression' risultano essere simmetrici. | ||

File:Bruxer SP2 .jpg|'''Figure 7:''' <math>\gamma _3=</math> Periodo silente meccanico rilevato elettrofisiologicamente sui masseteri di destra (tracce sovrapposte superiori) e di sinistra (tracce sovrapposte inferiori) | File:Bruxer SP2.jpg|'''Figure 7:''' <math>\gamma _3=</math> Periodo silente meccanico rilevato elettrofisiologicamente sui masseteri di destra (tracce sovrapposte superiori) e di sinistra (tracce sovrapposte inferiori) | ||

</gallery></center> | </gallery></center> | ||

Revision as of 14:13, 5 February 2023

Few studies have attempted to characterize the pain associated with bruxism (i.e., to examine the neurobiological and physiological characteristics of the mandibular muscles). Some clinical cases and small-scale studies suggest that certain drugs linked to the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and adrenergic systems can either suppress or exacerbate bruxism. Further, the majority of these pharmacological studies indicate that various classes of drugs can influence the muscular activity related to bruxism, without exerting any effect on OP. Therefore, the sensitization of the trigeminal nociceptive system and the facilitating effect on mandibular stretch reflexes and CNS hyperexcitability are neurophysiopathogenetic phenomena that can be correlated to pain in the craniofacial region. However, up to now, no correlation has been reported between OP, dysfunction of the mesencephalic nuclei, and facilitation of trigeminal nociception, except for a clinical study on a patient affected by pontine cavernoma, which highlighted a relative facilitation of the trigeminal nociceptive system through the blink reflex.

As anticipated we will take up the same diagnostic language presented for the patient Mary Poppins so that it becomes an assimilable and practicable model, and we will try to superimpose it on the present clinical case called 'Bruxer'. The subject was a 32-year-old man suffering from pronounced nocturnal and diurnal bruxism and chronic bilateral OP prevalent in the temporoparietal regions, with greater intensity and frequency on the left side. Neurological examination showed a contraction of the masseter muscles with pronounced stiffness of the jaw, diplopia and loss of visual acuity in the left eye, left gaze nystagmus with a rotary component, papillae with blurred borders and positive bilateral Babynski's, and polykinetic tendon reflexes in all four limbs.

Introduction

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24165294/

As anticipated in the chapter 'Bruxism' we will avoid indicating this disorder as an exclusive dental correlate and will seek a broader and essentially more neurophysiological description by making a brief excursus on dystonic phenomena, on 'Orofacial Pain' and only then will we consider the phenomenon 'bruxism' true and own. Subsequently we will move on to the presentation of the clinical case.

Dystonia is an involuntary, repetitive, sustained (tonic), or spasmodic (rapid or clonic) muscle contraction. The spectrum of dystonias can involve various regions of the body. Of interest to oral and maxillofacial surgeons are the cranial-cervical dystonias, in particular, orofacial dystonia (OFD). OFD is an involuntary, sustained contraction of the periorbital, facial, oromandibular, pharyngeal, laryngeal, or cervical muscles.[1] OFD can involve the masticatory, lower facial, and tongue muscles, which may result in trismus, bruxism, involuntary jaw opening or closure, and involuntary tongue movement.

The etiology of OFD is varied and includes genetic predisposition, injury to the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral trauma, medications, metabolic or toxic states, and neurodegenerative disease. However, in the majority of patients, no specific cause can be identified. An association was found among painful temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), migraine, tension-type headache, and sleep bruxism, although the association was only significant for chronic migraine. The association between painful TMDs and sleep bruxism significantly increased the risk for chronic migraine, followed by episodic migraine and episodic tension-type headache.[2]

Bruxism is the most frequently occurring oral movement disorder, and can occur in subjects while awake and during sleep. Both forms are likely to have different etiologies, and their diagnosis and treatment require different approaches. Treatment is indicated when bruxism causes pain in the masticatory system or leads to damage such as tooth wear or fractures of teeth, restorations, or even of implants. A focused review on the etiology of bruxism[3] concluded that there is a limited role for morphological factors in the etiology of bruxism, while psychological factors (e.g., stress) and pathophysiological factors (e.g., disturbances in central neurotransmitter systems) are more prominently involved.

Orofacial pain (OP), including pain from TMDs, exerts a modulatory effect on mandibular stretch reflexes.[4] Electrophysiological studies have shown that experimentally induced pain from injections of 5% hypertonic saline solution into the masseter muscle causes an increase in the peak-to-peak amplitude of the jaw jerk. This facilitatory effect appears to be related to an increased sensitivity of the fusimotor system, which at the same time causes muscle stiffness.[5] In addition, a number of animal studies of experimentally-induced muscle pain have shown that activation of the muscle nociceptors markedly influences the proprioceptive properties of the muscle spindles through a central neural pathway,[6] and that washing of the local algogenic substance causes a return to normal tendon reflexes.

However, few studies have attempted to characterize the pain associated with bruxism (i.e., to examine the neurobiological and physiological characteristics of the mandibular muscles). Some clinical cases and small-scale studies suggest that certain drugs linked to the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, and adrenergic systems can either suppress or exacerbate bruxism. Further, the majority of these pharmacological studies indicate that various classes of drugs can influence the muscular activity related to bruxism, without exerting any effect on OP.[7]

Therefore, the sensitization of the trigeminal nociceptive system and the facilitating effect on mandibular stretch reflexes and CNS hyperexcitability are neurophysiopathogenetic phenomena that can be correlated to pain in the craniofacial region. However, up to now, no correlation has been reported between OP, dysfunction of the mesencephalic nuclei, and facilitation of trigeminal nociception, except for a clinical study on a patient affected by pontine cavernoma, which highlighted a relative facilitation of the trigeminal nociceptive system through the blink reflex.[8]

Case report

As anticipated we will take up the same diagnostic language presented for the patient Mary Poppins so that it becomes an assimilable and practicable model, and we will try to superimpose it on the present clinical case called 'Bruxer'.

The subject was a 32-year-old man suffering from pronounced nocturnal and diurnal bruxism and chronic bilateral OP prevalent in the temporoparietal regions, with greater intensity and frequency on the left side. Neurological examination showed a contraction of the masseter muscles with pronounced stiffness of the jaw, diplopia and loss of visual acuity in the left eye, left gaze nystagmus with a rotary component, papillae with blurred borders and positive bilateral Babynski’s, and polykinetic tendon reflexes in all four limbs.

From what has been exposed in the previous chapters from the 'Introduction' to the chapters 'Logic of medical language' and the last chapter 'Bruxism', in addition to the complexity of the arguments and the vagueness of the verbal language, we could find ourselves faced with a clinical situation in which seems to dominate one of the contexts considered.

(it looks like it but....)

Unlike the patient with 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', the clinical case of our poor 'Bruxer' shows a phenomenon of overlapping of propositions, assertions and logical sentences in the dental and neurological context and apparently neither of the two obtains an absolute and clear compatibility and consistency. This has repercussions in the clinic in which all the actors involved (medical examiners) are right and contextually wrong, making the diagnostic conclusion inadequate and dangerous, but let's see the process as a whole step by step.

Significance of contexts

Nel il contesto odontoiatrico avremo le seguenti frasi ed asserzioni a cui diamo un valore numerico per facilitare la trattazione e cioè dove lo indica 'normalità' e 'anormalità e dunque positività del referto:

Negative MR report of the TMJ in Figure 2, Normalità, negatività del referto

Negative axiographic report for right condylar traces in Figure 3, Normalità, negatività del referto

Negative axiographic report for left condylar traces in Figure 4, Normalità, negatività del referto

Symmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5, Normalità, negatività del referto

In the dental context we will have the following sentences and statements to which we give a numerical value to facilitate the treatment, namely where it indicates 'normal' e abnormality and therefore positivity of the report:

Negative MR report of the TMJ in Figure 2, Normality, negativity of the report

Negative axiographic report for right condylar traces in Figure 3, Normality, negativity of the report

Negative axiographic report for left condylar traces in Figure 4, Normality, negativity of the report

Symmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5, Normality, negativity of the report

(ed è proprio qui che i contesti vanno in conflitto o meglio potrebbero i risultati non essere così determinanti)

Nel contesto neurologico avremo, perciò, le seguenti frasi ed asserzioni a cui diamo un valore numerico per facilitare la trattazione e cioè dove lo indica 'normalità' e 'anormalità e dunque positività del referto:

Presenza e simmetria dei Potenziali Evocati Motori delle Radici trigeminali in Figure 5, Normalità, negatività del referto

Presenza del jaw jerk con relativa asimmetria di ampiezza in Figure 6 Anormalità, negatività del referto* ( lo * è stato inserito per annotare una ambiguità del referto che andremo a descrivere dettagliatamente nella trattazione clinica)

Periodo silente elettrico e contestuale simmetria Figure 7, Normalità, negatività del referto

Demarcatore di Coerenza

Come abbiamo descritto nel capitolo ' 1° Clinical case: Hemimasticatory spasm' il è un rappresentativo peso specifico clinico, complesso da ricercare e mettere a punto perchè varia da disciplina a disciplina e per patologie, essenziale per non far collidere le asserzioni logiche e nelle procedure diagnostiche e fondamentale per inizializzare la decriptazione del codice di linguaggio macchina. Sostanzialmente permette di confermare la coerenza di una unione rispetto ad una altra e viceversa, dando un peso maggiore alla gravità delle asserzioni e del referto nel contesto appropriato.

Il peso di demarcazione , perciò, dà più significatività alle asserzioni più gravi nel contesto clinico da cui derivano e dunque al di là della maggiore o minore positività delle asserzioni oppure che comunque sono sempre verificate e rispettate, queste dovranno essere validate in funzione delle intrisneca gravità clinica moltiplicando la media dell'asserzione e per un dove lo indica 'Gravità bassa' mentre 'Gravità severa'.

Si potrebbe definire un demarcatore di coerenza come un numero reale compreso fra 0 e 1 nel caso in cui abbiamo più di due refertazioni e quindi un numero vicino allo zero corrisponderebbe ad una refertazione di 'Gravità bassa' mentre con un numero vicino allo uno ad una refertazione di 'Gravità severa'.

Per ricapitolare nel nostro caso 'Bruxer' abbiamo dunque:

dove

media del valore delle asserzioni cliniche nel contesto odontoiatrico e dunque

media del valore delle asserzioni cliniche nel contesto neurologico e dunque

refertazione di bassa gravità del contesto odontoiatrico

refertazione di massima gravità del contesto neurologico

in cui il 'demarcatore di coerenza ' definirà il percorso diagnostico nel seguente modo

Come si può notare nel nostro caso clinico 'Bruxer' abbiamo una lievissima pendenza diagnostica verso il contesto neurologico che ci permette, comunque, di intravedere più una componente neurologica piuttosto che odontoiatrica.

Una volta lavata via la miriade di dati normativi refertati positivamente, che generano conflittualità tra contesti, grazie al demarcatore di coerenza abbiamo un quadro molto più chiaro e lineare su cui approfondire l'analisi della funzionalità del Sistema Nervoso Centrale che nel nostro caso clinico 'Bruxer' si presenta alquanto intrigato per il basso peso diagnostico derivato dalle asserzioni neurologiche . Questo dato medio deriva principalmente da una ipotetica anomalia riguardante l'ampiezza del jaw jerk etichettata con un asterisco (*). Ne parleremo nella sezione dedicata a questo riflesso trigeminale.

Di conseguenza possiamo concentrarsi nell'intercettare i tests necessari per decriptare il codice del linguaggio macchina che il SNC invia all'esterno convertito in linguaggio verbale che a prima vista sembrerebbe riguardare una sorta di ipereflessia dei riflessi tendine. e nello specifico del jaw jerk.[9][10][11] Per confermare questa intuizione ipotesi è necessario un brainstorming del tipo 'Rete Neurale Cognitiva' abbreviata in 'RNC' presentato per la diagnostica del caso della nostra 'Mary Poppins' nel capitolo 'Encrypted code: Ephaptic transmission'.

Attraverso questo primo percorso diagnostico abbiamo, comunque, fatto passi avanti perchè, contrariamente a come è l'iter codificato nelle discipline odontoiatriche, stiamo intraprendendo un percorso neurofisiologico per decriptare il codice di linguaggio macchina del 'bruxismo'.

Per non appesantire la discussione tratteremo il secondo step diagnostico del modello Masticationpedia nel successivo capitolo intitolato 'Encrypted code: Hyperexcitability of the trigeminal system'

- ↑ Thompson PD, Obeso JA, Delgado G, Gallego J, Marsden CD. Focal dystonia of the jaw and differential diagnosis of unilateral jaw and masticatory spasm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:651–656. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.6.651. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar][Ref list]

- ↑ Fernandes G, Franco AL, Gonçalves DA, Speciali JG, Bigal ME, Camparis CM. Temporomandibular disorders, sleep bruxism, and primary headaches are mutually associated. J Orofac Pain. 2013;27(1):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- ↑ Lobbezoo F. Taking up challenges at the interface of wear and tear. J Dent Res. 2007;86(2):101–103. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600201.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar][Ref list]

- ↑ Dubner R, Ren K. Brainstem mechanisms of persistent pain following injury. J Orofac Pain. 2004;18(4):299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- ↑ Wang K, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Modulation of exteroceptive suppression periods in human jaw-closing muscles by local and remote experimental muscle pain. Pain. 1999;82(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00058-5.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar][Ref list]

- ↑ Ro JY, Capra NF. Modulation of jaw muscle spindle afferent activity following intramuscular injections with hypertonic saline. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):117–127.[PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- ↑ Winocur E, Gavish A, Voikovitch M, Emodi-Perlman A, Eli I. Drugs and bruxism: a critical review. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17(2):99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- ↑ Katsarava Z, Egelhof T, Kaube H, Diener HC, Limmroth V. Symptomatic migraine and sensitization of trigeminal nociception associated with contralateral pontine cavernoma. Pain. 2003;105(1–2):381–384.[PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- ↑ S Watanabe , H Mochizuki, I Nakashima, Y Itoyama. A case of primary Sjögren's syndrome with CNS disease mimicking chronic progressive multiple sclerosis.Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1998 Jul;38(7):658-62.

- ↑ Ibrahim M Norlinah, Kailash P Bhatia, Karen Ostergaard, Robin Howard, Gennarina Arabia, Niall P Quinn. Primary lateral sclerosis mimicking atypical parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2007 Oct.31;22(14):2057-62. doi: 10.1002/mds.21645.

- ↑ M Yoshida, N Murakami, Y Hashizume, A Takahashi. A clinicopathological study on 13 cases of motor neuron disease with dementia.Rinsho Shinkeigaku.1992 Nov;32(11):1193-202.

![{\displaystyle \delta _{n}=[0|1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cd35df3912a48e5b0b70d9cd5b2e1bee432c3272)

![{\displaystyle \gamma _{n}=[0|1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2f85d0ed73fa3e7903f0321e48668467c1277f4e)

![{\displaystyle \tau =[0|1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fbdc534cec0dcf1f070a551e40611eb83e8aca25)