Difference between revisions of "Systèmes complexes"

| Line 490: | Line 490: | ||

Le district du tronc cérébral est une zone de relais qui relie les centres supérieurs du cerveau, le cervelet et la moelle épinière, et fournit la principale innervation sensorielle et motrice du visage, de la tête et du cou par l'intermédiaire des nerfs crâniens. | Le district du tronc cérébral est une zone de relais qui relie les centres supérieurs du cerveau, le cervelet et la moelle épinière, et fournit la principale innervation sensorielle et motrice du visage, de la tête et du cou par l'intermédiaire des nerfs crâniens. | ||

Elle joue un rôle déterminant dans la régulation de la respiration, de la locomotion, de la posture, de l'équilibre, de l'excitation (y compris le contrôle intestinal, la vessie, la pression sanguine et le rythme cardiaque). Il est responsable de la régulation de nombreux réflexes, dont la déglutition, la toux et les vomissements.. | Elle joue un rôle déterminant dans la régulation de la respiration, de la locomotion, de la posture, de l'équilibre, de l'excitation (y compris le contrôle intestinal, la vessie, la pression sanguine et le rythme cardiaque). Il est responsable de la régulation de nombreux réflexes, dont la déglutition, la toux et les vomissements.. The brainstem is controlled by higher Cerebral Centers from cortical and subcortical regions, including the Basal Ganglia Nuclei and Diencephal, as well as feedback loops from the cerebellum and spinal cordNeuromodulation can be achieved by the ‘classical’ mode of glutammatergic neurotransmitters and GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid) through a primary excitation and inhibition of the ‘anatomical network’, but can also be achieved through the use of transmitters acting on G-proteinsThese neuromodulators include the monoamine (serotonine, noradrenaline, and dopamine) acetylcholine, as also glutamate and GABAIn addition, not only do neuropeptides and purines act as neuromodulators: so do other chemical mediators too, like Growth Factors which might have similar actions.<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Mascaro MB | | autore = Mascaro MB | ||

| autore2 = Prosdócimi FC | | autore2 = Prosdócimi FC | ||

| Line 511: | Line 511: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

The neural network described above does not end with the only correlation between trigeminal somatosensory centres and other motor areas but also strays into the amigdaloidei processes through a correlation with the trigeminal brainstem areaThe amygdala becomes active from fear, playing an important role in the emotional response to life-threatening situationsWhen lab rats feel threatened, they respond by biting ferociouslyThe force of the bite is regulated by the motor nuclei of the trigeminal system and trigeminal brainstem Me5The Me5 transmits proprioceptive signals from the Masticatory muscles and parodontal ligaments to trigeminal nuclei and motorsCentral Amygdaloid Nucleus (ACe) projections send connections to the trigeminal motor nucleus and reticular premotor formation and directly to the Me5. | |||

To confirm this, in a study conducted among mice, the neurons in the Central Amigdaloide nucleus (ACe) were marked after the injection of a retrograde tracer(Fast Blue), in the caudal nucleus of the Me5, indicating that the Amigdaloians send direct projections to the Me5, and suggest that the amygdala regulates the strength of the bite by modifying the neuronal activity in the Me5 through a neural facilitation.<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Shirasu M | | autore = Shirasu M | ||

| autore2 = Takahashi T | | autore2 = Takahashi T | ||

| Line 536: | Line 536: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

Modifying occlusal ratios can alter oral somatosensory functions and the rehabilitative treatments of the Masticatory system should restore somatosensory functions. However, it is unclear why some patients fail to adapt to the masticatory restoration, and sensomotor disorders remain. At first, they would seem to be structural changes, not just functional onesThe primary motor cortex of the face is involved in the generation and control of facial gold movements and sensory inputs or altered motor functions, which can lead to neuroplastic changes in the M1 cortical area<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Avivi-Arber L | | autore = Avivi-Arber L | ||

| autore2 = Lee JC | | autore2 = Lee JC | ||

| Line 556: | Line 556: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

== | ==Conclusive Considerations== | ||

In conclusion, it is clear from the premise, that the Masticatory system should be considered not certainly as a system simply governed by mechanical laws, but as a "Complex System" of indeterministic type, where one can quantify the "Emerging Behavior" only after stimulating it and then analysing the response evokedFigure 2). The Neuronal System also dialogues with its own encrypted machine language (potential action and ionic currents) and, therefore, it is not possible to interpret the symptoms referred to by the patient through natural language. | |||

This concept deepens knowledge of the state of health of a system because it elicits an answer from inside the network — or, at least, from a large part of it — by allocating normal and/or abnormal components of the various nodes of the network. In scientific terms, it also introduces a new paradigm in the study of the Masticatory System: the "Neuro Gnathology Function", that we will meet in due course in the chapter ‘Extraordinary Science’. | |||

Currently, the interpretation of the Emergent Behavior of the Mastication system in dentistry is performed only by analysing the voluntary valley response, through electromyographic recordings ‘EMG interference pattern’, and radiographic and axographic tests (replicators of mandibular movements). These can only be considered descriptive tests. | |||

The paradigm of gnathological descriptive tests faced a crisis years ago: despite an attempt to reorder the various axioms, schools of thought, and clinical-experimental strictness in the field of Temporomandibular Disorders (through the realization of a protocol called "Research Diagnostic Criteria" RDC/TMDs), this paradigm has not yet come to be accepted because of the scientific-clinical incompleteness of the procedure itself. It deserves, however, a particular reference to the RDC/TMD, at least for the commitment that was carried out by the authors and, at the same time, to scroll the limits. | |||

The RDC/TMD protocol was designed and initialized to avoid the loss of ‘standardized diagnostic criteria’ and evaluate a diagnostic standardization of empirical data at disposition. | |||

This protocol was supported by the National Institute for Dental Research (NIDR) and conducted at the University of Washington and the Group Health Corporative of Puget Sound, Seattle, Washington. Samuel F. Dworkin, M. Von Korff, and L. LeResche were the main investigators<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Dworkin SF | | autore = Dworkin SF | ||

| autore2 = Huggins KH | | autore2 = Huggins KH | ||

| Line 591: | Line 591: | ||

}}</ref>. | }}</ref>. | ||

To arrive at the formulation of the protocol of the ‘RDC’, a review of the literature of diagnostic methods in rehabilitative dentistry and TMDs, and subjected to validation and reproducibility, has been made. Taxonomic systems were taken into account by Farrar(1972)<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Farrar WB | | autore = Farrar WB | ||

| titolo = Differentiation of temporomandibular joint dysfunction to simplify treatment | | titolo = Differentiation of temporomandibular joint dysfunction to simplify treatment | ||

| Line 634: | Line 634: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref>, Eversole | }}</ref>, Eversole and Machado (1985)<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Eversole LR | | autore = Eversole LR | ||

| autore2 = Machado L | | autore2 = Machado L | ||

| Line 746: | Line 746: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref>, Bergamini | }}</ref>, Bergamini and Prayer-Galletti (1990)<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| autore = Prayer Galletti S | | autore = Prayer Galletti S | ||

| autore2 = Colonna MT | | autore2 = Colonna MT | ||

| Line 784: | Line 784: | ||

| LCCN = | | LCCN = | ||

| OCLC = | | OCLC = | ||

}}</ref>, | }}</ref>, andcompared them by granting them to a set of assessment criteria. | ||

The evaluation criteria were split into two categories that involve methodological considerations and clinical considerations. | |||

The end of the research came to the elimination, due to a lack of scientific and clinical validation, of a series of instrumental diagnostic methodologies like interferential electromyography (EMG Interference Pattern), Pantography, X-ray diagnostics, etc. These will be described in more detail in the next editions of Masticationpedia. This first target was, therefore, the scientific request of an "objective data"' and not generated by opinions, schools of thought or subjective evaluations of the phenomenon’. During the Workshop of the International Association for Dental Research (IADR) of 2008, preliminary results of the RDC/TMDs were presented in the endeavour to validate the project. | |||

The conclusion was that, to achieve a review and simultaneous validation of [RDC/TMD], it is essential that the tests should be able to make a differential diagnosis between TMD patients with pain and subjects without pain, and above all, discriminate against patients with TMD pain from patients with orofacial pain without TMD.<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| autore = Lobbezoo F | | autore = Lobbezoo F | ||

| autore2 = Visscher CM | | autore2 = Visscher CM | ||

| Line 809: | Line 809: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

< | <This last article, reconsidering pain as an essential symptom for the clinical interpretation, puts all the neurophysiological phenomenology in the game, not just this. | ||

To move more easily at ease in this medical branch, a different scientific-clinical approach is required, one that widens the horizons of competence in fields such as bioengineering and neurobiology. | |||

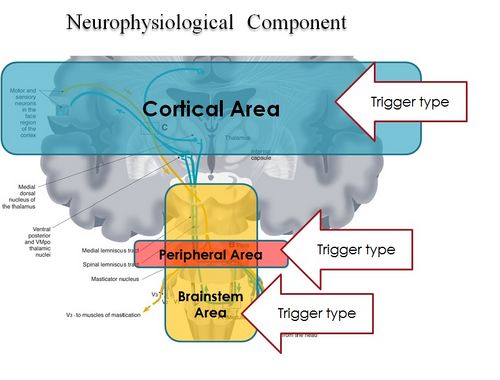

It is, therefore, essential to focus attention on how to take trigeminal electrophysiological signals in response to a series of triggers evoked by an electrophysiological device, treating data and determining an organic-functional value of the trigeminal and masticatory systems as anticipated by Marom Bikson and coll. in their. «''[[:File:Electrical stimulation of cranial nerves in cognition and disease.pdf|<span lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr">Electrical stimulation of cranial nerves in cognition and disease</span>]]''». | |||

We should think of a system that unifies the mastication and neurophysiological functions by introducing a new term: "'''Neuro-Gnathological Functions'''"<br>which will be the object of a dedicated chapter. | |||

{{Bib}} | {{Bib}} | ||

Revision as of 10:50, 18 March 2023

Après les chapitres précédents, nous devrions maintenant être en mesure de reconnaître que, tant en physique moderne qu'en biologie, un "système complexe" est un système dynamique à plusieurs composants, composé de différents sous-systèmes qui interagissent généralement les uns avec les autres. Ces systèmes sont généralement étudiés par des méthodes d'investigation "holistiques" ou par le calcul "total" des comportements des sous-systèmes individuels, ainsi que de leurs interactions mutuelles; ceux-ci peuvent être décrits de manière analytique par des modèles mathématiques, plutôt que de manière "réductionniste" (c'est-à-dire en décomposant et en analysant le système dans ses composantes). Les concepts d'auto-organisation et de "comportement émergent" sont typiques des systèmes complexes.

Dans ce chapitre, nous exposerons quelques contenus en faveur de cette vision plus stochastique et complexe des fonctions neuromotrices du système masticatoire.

Considération préliminaire

Ces dernières années, des développements parallèles dans différentes disciplines se sont concentrés sur ce que l'on a appelé la "connectivité", un concept utilisé pour comprendre et décrire les "systèmes complexes". Les conceptualisations et les fonctionnalisations de la connectivité ont largement évolué au sein de leurs frontières disciplinaires, mais il existe des similitudes évidentes dans ce concept et dans son application à travers les disciplines. Cependant, toute mise en œuvre du concept de connectivité implique des contraintes à la fois ontologiques et épistémologiques, ce qui nous amène à nous demander s'il existe un type ou un ensemble d'approches de la connectivité qui pourraient être appliquées à toutes les disciplines. Dans cette revue, nous explorons quatre défis ontologiques et épistémologiques liés à l'utilisation de la connectivité pour comprendre les systèmes complexes du point de vue de disciplines très différentes.

Dans le chapitre "Connectivité et systèmes complexes", nous introduirons enfin le concept de:

- définir l'unité fondamentale pour l'étude de la connectivité;

- séparer la connectivité structurelle de la connectivité fonctionnelle;

- la compréhension des comportements émergents; et

- mesurer la connectivité.

Nous devons maintenant considérer le profil complexe de la fonction masticatoire, pour pouvoir parler de "connectivité"[1]

Ce n'est que plus tard que l'importance de la fonction de mastication est devenue évidente en tant que système complexe, en raison de son interaction avec une multitude d'autres centres et systèmes nerveux (SNC), également distants d'un point de vue fonctionnel.[2]. La fonction de mastication, en effet, a toujours été considérée comme une fonction périphérique et isolée par rapport à la phonétique et à la mastication. Suite à cette interprétation, il y a eu d'innombrables points de vue qui se sont concentrés, et se concentrent encore, sur le diagnostic et la réhabilitation de la mastication exclusivement dans les maxillaires, en excluant toute corrélation multi-structurelle.

Ce type d'approche dénote un "réductionnisme" évident dans le contenu du système lui-même: en biologie, il est plus réaliste de considérer la fonctionnalité de systèmes tels que les "systèmes complexes" qui ne fonctionnent pas de manière linéaire. Ces systèmes utilisent une approche stochastique, dans laquelle l'interaction des différents composants génère un "comportement émergent" (EB)[3] of the same system.[4]

Ce résultat paradigmatique renverse la tendance à considérer le système masticatoire comme un simple organe cinématique et va bien au-delà de la procédure mécaniste traditionnelle de la gnathologie classique.

Cet aspect introduit également un type de profil indéterministe des fonctions biologiques, dans lequel la fonction d'un système se présente comme un réseau de multiples éléments liés. Outre l'interprétation de son état, ce système doit être stimulé de l'extérieur pour analyser la réponse évoquée, comme c'est le cas pour les systèmes indéterministes.[6]

Il est donc essentiel de passer d'un modèle simple et linéaire de la clinique dentaire à un modèle complexe stochastique de la neurophysiologie masticatoire.

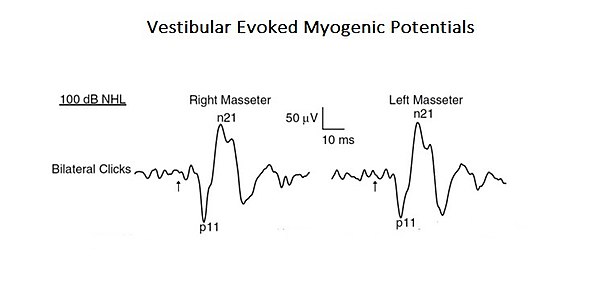

Pour confirmer cette approche plus complexe et intégrée de l'interprétation des fonctions de la mastication, une étude est présentée ici où le profil d'un "système complexe neuronal" émerge. Dans l'étude mentionnée, la connexion organique et fonctionnelle du système vestibulaire avec le système trigéminal a été analysée. [7]. Les stimuli acoustiques peuvent provoquer des réponses EMG-réflexes dans le muscle masséter, appelées potentiels myogéniques évoqués vestibulaires (PMVO). Même si ces résultats ont été précédemment attribués à l'activation des récepteurs cochléaires (sons de haute intensité), ceux-ci peuvent également activer les récepteurs vestibulaires. Comme les études anatomiques et physiologiques, tant chez l'animal que chez l'homme, ont montré que les muscles masséters sont une cible pour les entrées vestibulaires, les auteurs de cette étude ont réévalué la contribution vestibulaire pour les réflexes masséters. Il s'agit d'un exemple typique de système complexe de base, car il est constitué de deux systèmes nerveux crâniens seulement, mais qui interagissent en activant des circuits mono- et polysynaptiques (Figure 1).

Il serait opportun à ce stade d'introduire quelques sujets liés aux concepts mentionnés ci-dessus, ce qui permettrait de clarifier la raison d'être du projet Masticationpedia. Cela permettrait d'introduire les chapitres qui sont au cœur du projet.

Donc, l'objet est:

ils s'étendront à d'autres sujets essentiels, tels que la "segmentation du système nerveux trigéminal" dans le dernier chapitre, "La science extraordinaire".»

La mastication et les processus cognitifs

Récemment, la mastication a fait l'objet de discussions sur les effets de maintien et de soutien des performances cognitives.

Une élégante étude réalisée par fMR et tomographie par émission de positrons (TEP) a montré que la mastication entraîne une augmentation du flux sanguin cortical et active le cortex somatosensoriel supplémentaire, moteur et insulaire, ainsi que le striatum, le thalamus et le cervelet. La mastication juste avant d'effectuer une tâche cognitive augmente les niveaux d'oxygène dans le sang (BOLD du signal IRMf) dans le cortex préfrontal et l'hippocampe, des structures importantes impliquées dans l'apprentissage et la mémoire, améliorant ainsi la performance de la tâche.[8] Des études épidémiologiques antérieures ont montré qu'un nombre restreint de dents résiduelles, l'utilisation incongrue de prothèses et un développement limité de la force mandibulaire sont directement liés au développement de la démence, ce qui renforce l'idée que la mastication contribue au maintien des fonctions cognitives.[9].

Une étude récente a apporté de nouvelles preuves de l'interaction entre les processus masticatoires, l'apprentissage et la mémoire, en se concentrant sur la fonction de l'hippocampe qui est essentielle à la formation de nouveaux souvenirs[10]. Une dysharmonie occlusale, telle qu'une perte de dents et une augmentation de la dimension verticale de l'occlusion, entraîne un bruxisme ou une douleur des muscles de mastication et des troubles temporomandibulaires (TMD)[11][12]. Ainsi, pour décrire l'altération de la fonction de l'hippocampe dans une situation de réduction ou de fonction masticatoire anormale, les auteurs ont utilisé un modèle animal (souris) appelé "Molarless Senescence-Accelerated Prone" (SAMP8) afin d'établir un parallélisme avec l'homme. Chez les souris SAMP8, dont l'occlusion a été modifiée, l'augmentation de la dimension verticale occlusale d'environ 0,1 mm avec des matériaux dentaires a montré que la dysharmonie occlusale perturbe l'apprentissage et la mémoire. Ces animaux ont montré un déficit dépendant de l'âge dans l'apprentissage de l'espace à l'eau de Morris. [13][14]

L'augmentation de la dimension verticale de la morsure chez les souris SAMP8 diminue le nombre de cellules pyramidales[14] et le nombre de leurs épines dendritiques.[15] Il augmente également l'hypertrophie et l'hyperplasie des protéines fibrillaires des astrocytes dans les régions de l'hippocampe CA1 et CA3.[16]. Chez les rongeurs et les singes, les dysharmonies occlusales induites par une augmentation de la dimension verticale avec augmentation de l'acrylique sur les incisives[17][18] ou l'insertion du plan de morsure dans la mâchoire sont associées à une augmentation des taux de cortisol urinaire et à des taux plasmatiques élevés de corticostérone, ce qui suggère que la dysharmonie occlusale est également une source de stress.

À l'appui de cette notion, les souris SAMP8 présentant des déficits d'apprentissage montrent une augmentation marquée des niveaux plasmatiques de corticostérone[12] et sous-régulation du GR et du GRmRNA de l'hippocampe. La dysharmonie occlusale affecte également l'activité catécholaminergique. L'alternance de la fermeture de l'occlusion par l'insertion d'une plaque d'occlusion acrylique sur les incisives inférieures entraîne une augmentation des niveaux de dopamine et de noradrénaline dans l'hypothalamus et le cortex frontal[17][19], et des diminutions de la thyroxinaydroxylase, du cyclohydrochlorure de GTP et de la sérotonine immunoréactive dans le cortex cérébral et le noyau caudé, dans la substance nigra, dans le locus ceruleus et dans le noyau du raphé dorsal, qui sont similaires aux changements induits par le stress chronique.[20] Ces modifications des systèmes catécolaminergique et sérotoninergique, induites par les dysharmonies occlusales, affectent clairement l'innervation de l'hippocampe. Les conditions d'augmentation de la dimension verticale altèrent la neurogenèse et conduisent à l'apoptose dans le gyrus ippocampique en diminuant l'expression du cerveau ippocampique dérivé des facteurs neurotrophiques: tout cela pourrait contribuer aux changements dans l'apprentissage observé chez les animaux présentant une dysharmonie occlusale.[10]

Le tronc cérébral et la mastication

Le district du tronc cérébral est une zone de relais qui relie les centres supérieurs du cerveau, le cervelet et la moelle épinière, et fournit la principale innervation sensorielle et motrice du visage, de la tête et du cou par l'intermédiaire des nerfs crâniens.

Elle joue un rôle déterminant dans la régulation de la respiration, de la locomotion, de la posture, de l'équilibre, de l'excitation (y compris le contrôle intestinal, la vessie, la pression sanguine et le rythme cardiaque). Il est responsable de la régulation de nombreux réflexes, dont la déglutition, la toux et les vomissements.. The brainstem is controlled by higher Cerebral Centers from cortical and subcortical regions, including the Basal Ganglia Nuclei and Diencephal, as well as feedback loops from the cerebellum and spinal cordNeuromodulation can be achieved by the ‘classical’ mode of glutammatergic neurotransmitters and GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid) through a primary excitation and inhibition of the ‘anatomical network’, but can also be achieved through the use of transmitters acting on G-proteinsThese neuromodulators include the monoamine (serotonine, noradrenaline, and dopamine) acetylcholine, as also glutamate and GABAIn addition, not only do neuropeptides and purines act as neuromodulators: so do other chemical mediators too, like Growth Factors which might have similar actions.[21]

The neural network described above does not end with the only correlation between trigeminal somatosensory centres and other motor areas but also strays into the amigdaloidei processes through a correlation with the trigeminal brainstem areaThe amygdala becomes active from fear, playing an important role in the emotional response to life-threatening situationsWhen lab rats feel threatened, they respond by biting ferociouslyThe force of the bite is regulated by the motor nuclei of the trigeminal system and trigeminal brainstem Me5The Me5 transmits proprioceptive signals from the Masticatory muscles and parodontal ligaments to trigeminal nuclei and motorsCentral Amygdaloid Nucleus (ACe) projections send connections to the trigeminal motor nucleus and reticular premotor formation and directly to the Me5.

To confirm this, in a study conducted among mice, the neurons in the Central Amigdaloide nucleus (ACe) were marked after the injection of a retrograde tracer(Fast Blue), in the caudal nucleus of the Me5, indicating that the Amigdaloians send direct projections to the Me5, and suggest that the amygdala regulates the strength of the bite by modifying the neuronal activity in the Me5 through a neural facilitation.[22]

Modifying occlusal ratios can alter oral somatosensory functions and the rehabilitative treatments of the Masticatory system should restore somatosensory functions. However, it is unclear why some patients fail to adapt to the masticatory restoration, and sensomotor disorders remain. At first, they would seem to be structural changes, not just functional onesThe primary motor cortex of the face is involved in the generation and control of facial gold movements and sensory inputs or altered motor functions, which can lead to neuroplastic changes in the M1 cortical area[23]

Conclusive Considerations

In conclusion, it is clear from the premise, that the Masticatory system should be considered not certainly as a system simply governed by mechanical laws, but as a "Complex System" of indeterministic type, where one can quantify the "Emerging Behavior" only after stimulating it and then analysing the response evokedFigure 2). The Neuronal System also dialogues with its own encrypted machine language (potential action and ionic currents) and, therefore, it is not possible to interpret the symptoms referred to by the patient through natural language.

This concept deepens knowledge of the state of health of a system because it elicits an answer from inside the network — or, at least, from a large part of it — by allocating normal and/or abnormal components of the various nodes of the network. In scientific terms, it also introduces a new paradigm in the study of the Masticatory System: the "Neuro Gnathology Function", that we will meet in due course in the chapter ‘Extraordinary Science’.

Currently, the interpretation of the Emergent Behavior of the Mastication system in dentistry is performed only by analysing the voluntary valley response, through electromyographic recordings ‘EMG interference pattern’, and radiographic and axographic tests (replicators of mandibular movements). These can only be considered descriptive tests.

The paradigm of gnathological descriptive tests faced a crisis years ago: despite an attempt to reorder the various axioms, schools of thought, and clinical-experimental strictness in the field of Temporomandibular Disorders (through the realization of a protocol called "Research Diagnostic Criteria" RDC/TMDs), this paradigm has not yet come to be accepted because of the scientific-clinical incompleteness of the procedure itself. It deserves, however, a particular reference to the RDC/TMD, at least for the commitment that was carried out by the authors and, at the same time, to scroll the limits.

The RDC/TMD protocol was designed and initialized to avoid the loss of ‘standardized diagnostic criteria’ and evaluate a diagnostic standardization of empirical data at disposition. This protocol was supported by the National Institute for Dental Research (NIDR) and conducted at the University of Washington and the Group Health Corporative of Puget Sound, Seattle, Washington. Samuel F. Dworkin, M. Von Korff, and L. LeResche were the main investigators[24].

To arrive at the formulation of the protocol of the ‘RDC’, a review of the literature of diagnostic methods in rehabilitative dentistry and TMDs, and subjected to validation and reproducibility, has been made. Taxonomic systems were taken into account by Farrar(1972)[25][26], Eversole and Machado (1985)[27], Bell (1986)[28], Fricton (1989)[29], American Academy of Craniomandibular Disorders (AACD) (1990)[30], Talley (1990)[31], Bergamini and Prayer-Galletti (1990)[32], Truelove (1992)[33], andcompared them by granting them to a set of assessment criteria. The evaluation criteria were split into two categories that involve methodological considerations and clinical considerations.

The end of the research came to the elimination, due to a lack of scientific and clinical validation, of a series of instrumental diagnostic methodologies like interferential electromyography (EMG Interference Pattern), Pantography, X-ray diagnostics, etc. These will be described in more detail in the next editions of Masticationpedia. This first target was, therefore, the scientific request of an "objective data"' and not generated by opinions, schools of thought or subjective evaluations of the phenomenon’. During the Workshop of the International Association for Dental Research (IADR) of 2008, preliminary results of the RDC/TMDs were presented in the endeavour to validate the project.

The conclusion was that, to achieve a review and simultaneous validation of [RDC/TMD], it is essential that the tests should be able to make a differential diagnosis between TMD patients with pain and subjects without pain, and above all, discriminate against patients with TMD pain from patients with orofacial pain without TMD.[34]

<This last article, reconsidering pain as an essential symptom for the clinical interpretation, puts all the neurophysiological phenomenology in the game, not just this. To move more easily at ease in this medical branch, a different scientific-clinical approach is required, one that widens the horizons of competence in fields such as bioengineering and neurobiology.

It is, therefore, essential to focus attention on how to take trigeminal electrophysiological signals in response to a series of triggers evoked by an electrophysiological device, treating data and determining an organic-functional value of the trigeminal and masticatory systems as anticipated by Marom Bikson and coll. in their. «Electrical stimulation of cranial nerves in cognition and disease».

We should think of a system that unifies the mastication and neurophysiological functions by introducing a new term: "Neuro-Gnathological Functions"

which will be the object of a dedicated chapter.

- ↑ Turnbull L, Hütt MT, Ioannides AA, Kininmonth S, Poeppl R, Tockner K, Bracken LJ, Keesstra S, Liu L, Masselink R, Parsons AJ, «Connectivity and complex systems: learning from a multi-disciplinary perspective», in Appl Netw Sci, 2018».

PMID:30839779 - PMCID:PMC6214298

DOI:10.1007/s41109-018-0067-2

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Viggiano A, Manara R, Conforti R, Paccone A, Secondulfo C, Lorusso L, Sbordone L, Di Salle F, Monda M, Tedeschi G, Esposito F, «Mastication induces long-term increases in blood perfusion of the trigeminal principal nucleus», in Neuroscience, Elsevier, 2015».

PMID:26477983

DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.10.017 - ↑ Florio T, Capozzo A, Cellini R, Pizzuti G, Staderini EM, Scarnati E, «Unilateral lesions of the pedunculopontine nucleus do not alleviate subthalamic nucleus-mediated anticipatory responding in a delayed sensorimotor task in the rat», in Behav Brain Res, 2001».

PMID:11704255

DOI:10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00248-0 - ↑ de Boer RJ, Perelson AS, «Size and connectivity as emergent properties of a developing immune network», in J Theor Biol, 1991».

PMID:2062103

DOI:10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80313-3 - ↑ Iyer-Biswas S, Hayot F, Jayaprakash C, «Stochasticity of gene products from transcriptional pulsing», in Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys, 2009».

PMID:19391975

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.79.031911

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Lewis ER, MacGregor RJ, «On indeterminism, chaos, and small number particle systems in the brain», in J Integr Neurosci, 2006».

PMID:16783870

DOI:10.1142/s0219635206001112 - ↑ Deriu F, Ortu E, Capobianco S, Giaconi E, Melis F, Aiello E, Rothwell JC, Tolu E, «Origin of sound-evoked EMG responses in human masseter muscles», in J Physiol, 2007».

PMID:17234698 - PMCID:PMC2075422

DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123240

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Yamada K, Park H, Sato S, Onozuka M, Kubo K, Yamamoto T, «Dynorphin-A immunoreactive terminals on the neuronal somata of rat mesencephalic trigeminalnucleus», in Neurosci Lett, Elsevier Ireland, 2008».

PMID:18455871

DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.030 - ↑ Kondo K, Niino M, Shido K, «Dementia. A case-control study of Alzheimer's disease in Japan - significance of life-styles», 1994».

PMID:7866485

DOI:10.1159/000106741 - ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kubo KY, Ichihashi Y, Kurata C, Iinuma M, Mori D, Katayama T, Miyake H, Fujiwara S, Tamura Y, «Masticatory function and cognitive function», in Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn, 2010».

PMID:21174943

DOI:10.2535/ofaj.87.135

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Christensen J, «Effect of occlusion-raising procedures on the chewing system», in Dent Pract Dent Rec, 1970».

PMID:5266427 - ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ichihashi Y, Arakawa Y, Iinuma M, Tamura Y, Kubo KY, Iwaku F, Sato Y, Onozuka M, «Occlusal disharmony attenuates glucocorticoid negative feedback in aged SAMP8 mice», in Neurosci Lett, 2007».

PMID:17928141

DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.020 - ↑ Arakawa Y, Ichihashi Y, Iinuma M, Tamura Y, Iwaku F, Kubo KY, «Duration-dependent effects of the bite-raised condition on hippocampal function in SAMP8 mice», in Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn, 2007».

PMID:18186225

DOI:10.2535/ofaj.84.115

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kubo KY, Yamada Y, Iinuma M, Iwaku F, Tamura Y, Watanabe K, Nakamura H, Onozuka M, «Occlusal disharmony induces spatial memory impairment and hippocampal neuron degeneration via stress in SAMP8 mice», in Neurosci Lett, Elsevier Ireland, 2007».

PMID:17207572

DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2006.12.020 - ↑ Kubo KY, Kojo A, Yamamoto T, Onozuka M, «The bite-raised condition in aged SAMP8 mice induces dendritic spine changes in the hippocampal region», in Neurosci Lett, 2008».

PMID:18614288

DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.027 - ↑ Ichihashi Y, Saito N, Arakawa Y, Kurata C, Iinuma M, Tamura Y, Iwaku F, Kubo KY, «The bite-raised condition in aged SAMP8 mice reduces the expression of glucocorticoid receptors in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus», in Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn, 2008».

PMID:18464530

DOI:10.2535/ofaj.84.137

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ 17.0 17.1 Areso MP, Giralt MT, Sainz B, Prieto M, García-Vallejo P, Gómez FM, «Occlusal disharmonies modulate central catecholaminergic activity in the rat», in J Dent Res, 1999».

PMID:10371243

DOI:10.1177/00220345990780060301 - ↑ Yoshihara T, Matsumoto Y, Ogura T, «Occlusal disharmony affects plasma corticosterone and hypothalamic noradrenaline release in rats», in J Dent Res, 2001».

PMID:11808768

DOI:10.1177/00220345010800121301 - ↑ Gómez FM, Areso MP, Giralt MT, Sainz B, García-Vallejo P, «Effects of dopaminergic drugs, occlusal disharmonies, and chronic stress on non-functional masticatory activity in the rat, assessed by incisal attrition», in J Dent Res, 1998».

PMID:9649174

DOI:10.1177/00220345980770061001 - ↑ Feldman S, Weidenfeld J, «Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists in the hippocampus modify the negative feedback following neural stimuli», in Brain Res, Elsevier Science B.V., 1999».

PMID:10064785

DOI:10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01054-9 - ↑ Mascaro MB, Prosdócimi FC, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF, «Forebrain projections to brainstem nuclei involved in the control of mandibular movements in rats», in Eur J Oral Sci, 2009, São Paulo, Brazil».

PMID:20121930

DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00686.x - ↑ Shirasu M, Takahashi T, Yamamoto T, Itoh K, Sato S, Nakamura H, «Direct projections from the central amygdaloid nucleus to the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus in rats», in Brain Res, 2011».

PMID:21640334

DOI:10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.026 - ↑ Avivi-Arber L, Lee JC, Sessle BJ, «Dental Occlusal Changes Induce Motor Cortex Neuroplasticity», in J Dent Res, International & American Associations for Dental Research, 2015, Toronto, Canada».

PMID:26310722

DOI:10.1177/0022034515602478 - ↑ Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, Wilson L, Mancl L, Turner J, Massoth D, LeResche L, Truelove E, «A randomized clinical trial using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders-axis II to target clinic cases for a tailored self-care TMD treatment program», in J Orofac Pain, 2002».

PMID:11889659 - ↑ Farrar WB, «Differentiation of temporomandibular joint dysfunction to simplify treatment», in J Prosthet Dent, 1972».

PMID:4508486

DOI:10.1016/0022-3913(72)90113-8 - ↑ Farrar WB, «Controversial syndrome», in J Am Dent Assoc, Elsevier Inc, 1972».

PMID:4503595

DOI:10.14219/jada.archive.1972.0286 - ↑ Eversole LR, Machado L, «Temporomandibular joint internal derangements and associated neuromuscular disorders», in J Am Dent Assoc, 1985».

PMID:3882811

DOI:10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0283 - ↑ Storum KA, Bell WH, «The effect of physical rehabilitation on mandibular function after ramus osteotomies», in J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 1986».

PMID:3456031

DOI:10.1016/0278-2391(86)90188-6 - ↑ Schiffman E, Anderson G, Fricton J, Burton K, Schellhas K, «Diagnostic criteria for intraarticular T.M. disorders», in Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 1989».

PMID:2791516

DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00628.x - ↑ Phillips DJ Jr, Gelb M, Brown CR, Kinderknecht KE, Neff PA, Kirk WS Jr, Schellhas KP, Biggs JH 3rd, Williams B, «Guide to evaluation of permanent impairment of the temporomandibular joint», in Cranio, American Academy of Head, Neck and Facial Pain; American Academy of Orofacial Pain; American Academy of Pain Management; American College of Prosthodontists; American Equilibration Society and Society of Occlusal Studies; American Society of Maxillofacial Surgeons; American Society of Temporomandibular Joint Surgeons; International College of Cranio-mandibular Orthopedics; Society for Occlusal Studies, 1997».

PMID:9586521 - ↑ Talley RL, Murphy GJ, Smith SD, Baylin MA, Haden JL, «Standards for the history, examination, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders(TMD): a position paper», in Cranio, American Academy of Head, Neck and Facial Pain, 1990».

PMID:2098190

DOI:10.1080/08869634.1990.11678302 - ↑ Prayer Galletti S, Colonna MT, Meringolo P, «The psychological aspects of craniocervicomandibular pain dysfunction pathology», in Minerva Stomatol, 1990».

PMID:2398856 - ↑ Truelove EL, Sommers EE, LeResche L, Dworkin SF, Von Korff M, «Clinical diagnostic criteria for TMD. New classification permits multiple diagnoses», in J Am Dent Assoc, 1992».

PMID:1290490

DOI:10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0094 - ↑ Lobbezoo F, Visscher CM, Naeije M, «Some remarks on the RDC/TMD Validation Project: report of an IADR/Toronto-2008 workshop discussion», in J Oral Rehabil, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), 2010, Amsterdam, The Netherlands».

PMID:20374440

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02091.x

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system