Intermittierende Gesichtskrämpfe als Zeichen eines rezidivierenden pleomorphen Adenoms

| Title | Intermittierende Gesichtskrämpfe als Zeichen eines rezidivierenden pleomorphen Adenoms |

| Authors | Rosalie A Machado · Sami P Moubayed · Azita Khorsandi · Juan C Hernandez-Prera · Mark L Urken |

| Source | Document |

| Date | 2017 |

| Journal | World J Clin Oncol |

| DOI | 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.86 |

| PUBMED | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35287260/ |

| PDF copy | |

| License | Template:CC BY-NC |

| This resource has been identified as a Free Scientific Resource, this is why Masticationpedia presents it here as a mean of gratitude toward the Authors, with appreciation for their choice of releasing it open to anyone's access | |

This is free scientific content. It has been released with a free license, this is why we can present it here now, for your convenience. Free knowledge, free access to scientific knowledge is a right of yours; it helps Science to grow, it helps you to have access to Science

This content was relased with a Template:CC BY-NC license.

You might perhaps wish to thank the Author/s

Intermittierende Gesichtskrämpfe als Anzeichen eines rezidivierenden pleomorphen Adenoms

Free resource by Rosalie A Machado · Sami P Moubayed · Azita Khorsandi · Juan C Hernandez-Prera · Mark L Urken

|

Abstrakt

Die enge anatomische Beziehung des Gesichtsnervs zum Parotisparenchym hat einen erheblichen Einfluss auf die auftretenden Anzeichen und Symptome sowie die Diagnose und Behandlung von Parotisneoplasien. Allerdings wurde unseres Wissens nach eine Hyperaktivität dieses Nervs, die sich als Gesichtskrampf äußert, nie als Anzeichen oder Symptom einer bösartigen Erkrankung der Ohrspeicheldrüse beschrieben. Wir berichten über einen Fall eines Karzinoms, das aus einem rezidivierenden pleomorphen Adenom der linken Ohrspeicheldrüse (d. h. einem Karzinom ex pleomorphem Adenom) entstand und mit hemifazialen Spasmen einherging. Wir skizzieren die Differentialdiagnose des Hemifacialispasmus sowie eine vorgeschlagene Pathophysiologie. Gesichtslähmungen, Lymphknotenvergrößerungen, Hautbeteiligung und Schmerzen wurden alle mit bösartigen Erkrankungen der Ohrspeicheldrüse in Verbindung gebracht. Bisher wurde nicht über die Entwicklung eines Gesichtsspasmus bei bösartigen Erkrankungen der Ohrspeicheldrüse berichtet. Die häufigsten Ursachen für hemifazialen Spasmus sind Gefäßkompression des ipsilateralen Gesichtsnervs im Kleinhirnbrückenwinkel (als primär oder idiopathisch bezeichnet) (62 %), erblich bedingt (2 %), sekundär zu Bell-Lähmung oder Gesichtsnervenverletzung (17 %). Hemifaziale Spasmen imitieren (psychogen, Tics, Dystonie, Myoklonus, Myokymie, Myorthythmie und hemimastikatorischer Spasmus) (17 %). Hemifacialer Spasmus wurde nicht im Zusammenhang mit einem bösartigen Parotistumor berichtet, muss aber bei der Differenzialdiagnose dieses vorliegenden Symptoms berücksichtigt werden.

Schlüsselwörter: Gesichtskrampf, pleomorphes Adenom, gutartiger gemischter Parotistumor, rekonstruktive Chirurgie, Speicheldrüsen

Kerntipp: Dieser Bericht stellt den ersten Fall eines hemifazialen Spasmus dar, der mit der Umwandlung eines rezidivierenden pleomorphen Adenoms in ein Karzinom ohne pleomorphes Adenom einhergeht. Die Ursache hemifazialer Spasmen wird diskutiert.

Gehe zu:

INTRODUCTION

The intimate anatomical relationship of the facial nerve to the parotid gland has a significant influence on the symptoms/signs, diagnosis, and treatment of parotid neoplasms[1]. Involvement of the facial nerve by parotid malignancies usually results in partial or total hemifacial paralysis[2]. However, to our knowledge, hyperactivity of this nerve presenting as facial spasm has not been reported as the presenting feature of a malignant parotid tumor. Facial spasm has nonetheless been reported twice in the literature as a presenting feature of a benign parotid tumor[3]. We report a case of carcinoma arising in recurrent pleomorphic adenoma (i.e., carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma) that presented with hemifacial spasms. We outline the differential diagnosis of hemifacial spasm as well as a proposed pathophysiology.

This is a single institutional case report in a tertiary referral hospital. Institutional Review Board was not required to report one case at our institution.

Go to:

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old female smoker had a history of a pleomorphic adenoma in the left parotid gland treated with a superficial parotidectomy at the age of 18. Nineteen years following that surgery, the patient presented with multifocal recurrence. Surgical exploration was undertaken and the tumor was found inseparable from the facial nerve. At that time, the resection was abandoned and the facial nerve was not sacrificed and gross disease was left in the parotid bed. The patient underwent external beam radiation therapy and the size of the tumor remained stable for 10 years on serial computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) monitoring. The patient had been clinically asymptomatic until she started developing intermittent ipsilateral hemifacial spasms occurring spontaneously and involving all portions of the left facial musculature, which prompted her to return for evaluation.

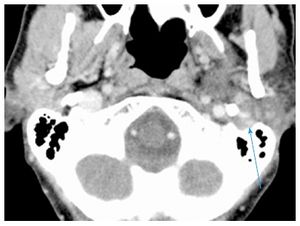

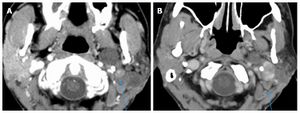

Repeat CT scan showed enlargement of avidly and uniformly enhancing solid tumor without areas of necrosis or extracapsular extension with extension into the left stylomastoid foramen, along with suspicious changes in enlarged (15 mm) left level IV lymph node (Figure (Figure1A).1A). Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the tumor was suspicious for carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. After a negative systemic metastatic work-up, the patient was brought to the operating room for a radical parotidectomy with facial nerve sacrifice, ipsilateral selective neck dissection (levels I-IV), and a de-epithelialized anterolateral thigh free flap for volume restoration and to enhance wound healing. The vertical segment of the facial nerve in the mastoid was exposed. Primary facial nerve repair was performed using sural nerve grafting from the main trunk to the temporal branch of the facial nerve, nerve to masseter grafting to the dominant midfacial branches of the facial nerve, together with construction of an oral commissure suspension with a fascia lata sling.

Final surgical pathology confirmed a 5.2 cm pleomorphic adenoma with a multinodular growth pattern. Well-circumscribed neoplastic nodules of variable sizes were embedded in densely fibrotic connective tissue (Figure (Figure2).2). Nerve bundles were also entrapped in the scar tissue in-between the nodules, but no true perineural invasion was detected. Within the nodules, two foci of early non-invasive carcinoma were noted. Within one nodule a 4 mm focus of malignant cells surrounded by benign epithelial elements was identified. In a separate nodule, an intraductal malignant neoplastic proliferation with an intact benign myoepithelial cell rim was also noted. None of the malignant neoplastic foci showed invasion into adjacent fibroadipose tissue and nerves. Thirteen level II-V lymph nodes were negative for tumor involvement. The primary tumor was staged as rT4N0M0.

The hemifacial spasms subsided after surgery, and the patient remains disease free at 6 mo of follow-up. The patient has recovered facial tone but has yet to develop dynamic muscular activity.

Go to:

DISCUSSION

Zbären et al[4] reported that pleomorphic adenomas comprised 60% of all of their benign and malignant parotid neoplasms. When left untreated, pleomorphic adenoma has a malignant transformation risk of 5% to 25% over a span of 15-20 years[5]. The risk of recurrence after primary superficial parotidectomy is 2%-5%[4], and malignant change in recurrent pleomorphic adenomas has an incidence of 2%-24%[6]. Zbären et al[4] postulates that the risk of de novo malignant change increases with time from first presentation and the number of recurrent episodes of the tumor.

Treatment of recurrent pleomorphic adenoma involves primary surgery that can either be a superficial or total parotidectomy based on the site of the recurrence and the extent of previous facial nerve exploration[6]. Adjuvant radiotherapy is another treatment option that is suitable for patients whose tumor is not completely excised[6]. According to Witt et al, retrospective analysis provides evidence that radiotherapy improves local control of this tumor[6]. The risk of malignant change in salivary glands following radiation therapy to the neck in 11047 patients with Hodgkins Lymphoma was investigated by Boukheris et al[7]. They reported that 21 patients developed salivary gland carcinoma with an observed-to-expected ratio of 16.9 and a confidence interval of 95%[7]. The risk was highest in patients under 20 years of age and those who survived more than 10 years[7].

In a review of the literature, Gnepp reported that carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma was present in 3.6% of all salivary gland neoplasms, 6.2% of all mixed tumors, and 11.6% of all malignant salivary gland neoplasms[2]. The malignant tumor is mainly found between the sixth to eighth decades of life[2]. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma represents a malignant change in a primary or recurrent pleomorphic adenoma[2]. Nouraei et al[8] and Zbären et al[4] reported that 25% of their 28 patients and 21% of their 24 patients, respectively, had a previously treated parotid adenoma. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma predominantly affects the major salivary glands with a majority of cases noted in the parotid and submandibular glands[2]. Nouraei et al[8] and Olsen et al[9] reported that the carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma was located in the parotid gland in of 96% and 86% of their cases, respectively. The most common clinical presentation of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma is as a firm mass in the parotid gland[2]. This tumor though typically non-invasive, confined to the capsule of the parotid adenoma and asymptomatic, has been reported to become invasive and involve local structures[2].

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma may present with pain when it is associated with invasion of local tissues[2]. Involvement of the facial nerve causes facial paresis or palsy[2]. Olsen et al[9] reported that 32% of the patients in their series had facial nerve involvement manifesting as partial or complete facial muscle weakness. Rarely, patients presented with skin ulceration, tumor fungation, skin fixation, palpable lymphadenopathy and dysphagia[2].

No case of hemifacial spasms or twitching associated with carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma or any other parotid or submandibular gland malignancies has been reported in the literature. The only malignant neoplasm presenting with facial spasm that we identified in the literature was a malignant astrocytoma located at the cerebellopontine angle[10]. Following resection of that tumor, the facial spasms resolved[10]. The two cases of hemifacial spasm have been reported with benign parotid tumors. Behbehani et al[11] reported the case of a 47-year-old man who presented with a right parotid mass and hemifacial spasm. The hemifacial spasms did not abate following surgery, but responded 8 mo later to botulinum toxin-A injections[11]. Destee et al[3] also reported a case of a pleomorphic adenoma in a 70 year-old man who presented with hemifacial spasms. During total parotidectomy, it was noted that the facial nerve was pale and appeared ischemic[3]. The hemifacial spasms reduced 8 days post operatively and had almost completely subsided within 6 mo[3].

The most common causes of hemifacial spasm are vascular compression of the ipsilateral facial nerve at the cerebellopontine angle (termed primary or idiopathic) (62%), hereditary (2%), secondary to Bell’s palsy or facial nerve injury (17%), and hemifacial spasm mimickers (psychogenic, tics, dystonia, myoclonus, myokymia, myorthythmia, and hemimasticatory spasm) (17%)[12]. In addition to a thorough history and a complete neurological examination, some authors recommend magnetic resonance imaging and angiography of the cerebellopontine angle[12]. However, such imaging may not be cost-effective in all patients[13], as the presence of an ectatic artery on magnetic resonance imaging may not be specific for hemifacial spasms[12]. Therefore, this may be reserved for patients with atypical features such as numbness and weakness[13].

The authors postulate that in this patient the hemifacial spasm commenced with the onset of the malignant transformation in the recurrent pleomorphic adenoma in the parotid gland. In the absence of any evidence of perineural invasion, we believe that peri-tumoral inflammatory responses caused the neural stimulation that resulted in hemifacial spasm. This patient did not have any prior ear surgery or any other known etiology to account for this symptom. An alternative explanation to the patient’s neurological symptoms is external compression to the facial nerve. This could be related to the dense fibrotic tissue surrounding both tumor nodules and nerves or to direct tumor extension into the left stylomastoid foramen[14] (Figure (Figure3).3). The latter mechanism has been previously proposed by Blevins et al[14].

In conclusion, we present the first case of hemifacial spasm in conjunction with transformation of a recurrent pleomorphic adenoma into a carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. The pathophysiology of hemifacial spasms is discussed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the generous support of this research by the Mount Sinai Health System and the THANC Foundation.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 56-year-old female with a history of recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the left parotid gland treated with surgery and external beam radiation therapy presented with ipsilateral hemifacial spasm.

Clinical diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis is a malignant change in a parotid pleomorphic adenoma with involvement of the facial nerve.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is the stimulation of facial nerve by perineural invasion or an inflammatory reaction caused by malignant parotid tumor.

Imaging diagnosis

Repeat CT scan showed enlargement of avidly and uniformly enhancing solid tumor without areas of necrosis or extracapsular extension with extension into the left stylomastoid foramen, along with suspicious changes in enlarged (15 mm) left level IV lymph node (Figure (Figure1A1A).

Pathological diagnosis

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the tumor was suspicious for carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Final surgical pathology confirmed a 5.2 cm pleomorphic adenoma with a multinodular growth pattern with two foci of early non-invasive carcinoma and no malignant spread to adjacent fibroadipose tissue, nerves or thirteen level II-V lymph nodes.

Treatment

A radical parotidectomy with facial nerve sacrifice, ipsilateral selective neck dissection (levels I-IV), and a de-epithelialized anterolateral thigh free flap was performed. A sural nerve grafting from the main trunk of the facial nerve to its branches and an oral commissure suspension with a fascia lata sling was done.

Experiences and lessons

The authors postulate that the hemifacial spasm commenced with the onset of the malignant transformation in the recurrent pleomorphic adenoma in the ipsilateral parotid gland. In the absence of any evidence of perineural invasion, they believe that peri-tumoral inflammatory responses caused the neural stimulation that resulted in hemifacial spasm.

Peer-review

This is the first reported case of malignant transformation of a recurrent pleomorphic adenoma in a parotid gland presenting with ipsilateral hemifacial spasm. In the absence of evidence of perineural invasion of the ipsilateral facial nerve, it is postulated that peri-tumoral inflammatory responses were responsible for the excitation of this nerve and the resultant hemifacial spasm.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This case report was exempt from the Institutional Review Board standards at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York.

Informed consent statement: This case report was exempt from obtaining informed consent based on Institutional Review Board standards at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: October 28, 2016

First decision: December 1, 2016

Article in press: January 3, 2017

P- Reviewer: Sedassari BT, Schneider S, Takahashi H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

1. Flint PW. Cummings Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

2. Antony J, Gopalan V, Smith RA, Lam AK. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a comprehensive review of clinical, pathological and molecular data. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Destee A, Bouchez B, Pellegrin P, Warot P. Hemifacial spasm associated with a mixed benign parotid tumour. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:189–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Zbären P, Tschumi I, Nuyens M, Stauffer E. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Am J Surg. 2005;189:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Seifert G. Histopathology of malignant salivary gland tumours. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1992;28B:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Witt RL, Eisele DW, Morton RP, Nicolai P, Poorten VV, Zbären P. Etiology and management of recurrent parotid pleomorphic adenoma. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:888–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Boukheris H, Ron E, Dores GM, Stovall M, Smith SA, Curtis RE. Risk of radiation-related salivary gland carcinomas among survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2008;113:3153–3159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Nouraei SA, Hope KL, Kelly CG, McLean NR, Soames JV. Carcinoma ex benign pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1206–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Olsen KD, Lewis JE. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a clinincopathological review. Head Neck. 2001;23:705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Castiglione M, Broggi M, Cordella R, Acerbi F, Ferroli P. Immediate disappearance of hemifacial spasm after partial removal of ponto-medullary junction anaplastic astrocytoma: case report. Neurosurg Rev. 2015;38:385–390; discussion 390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Behbehani R, Hussain AE, Hussain AN. Parotid tumor presenting with hemifacial spasm. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:141–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Yaltho TC, Jankovic J. The many faces of hemifacial spasm: differential diagnosis of unilateral facial spasms. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1582–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Tan NC, Chan LL, Tan EK. Hemifacial spasm and involuntary facial movements. QJM. 2002;95:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Blevins NH, Jackler RK, Kaplan MJ, Boles R. Facial paralysis due to benign parotid tumors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]