Hemimasticatory spasm

| Other languages: |

English ·

Italiano ·

Français ·

Deutsch ·

Español

|

This chapter and the series of sub-chapters will be mainly dedicated to the clinical case of our poor patient Mary Poppins who had to wait 10 years to get a certain and detailed diagnosis of 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', being between two focuses that of the dental and neurological context. besides all the other branches of medicine encountered in the diagnostic path, such as dermatology which diagnosed 'Morfea'. It would be too hasty to dismiss this clinical event by confirming the diagnosis of Hemimasticatory Spasm without understanding the reason for the diagnostic delay and even less to neglect the elements that could help the clinician to formulate a diagnosis in a more rapid and detailed way.

In this section of Masticationpedia, therefore, we would like to begin to lay the foundations for a more formal language in medical diagnostics of the mathematical type and not of the classic model in which the ambiguity and vagueness of the language can complicate the diagnostic process with decennial delays to times dangerous for the life of the human being. We will therefore resume some contents already proposed in the 'Introduction' section and make them practical and clinically essential in the diagnosis of our patient Mary Poppins.

Introduction

Before getting to the heart of the discussion regarding the pathology of our patient Mary Poppins, which from the previous chapters seems to be of a neuromotor type, in particular a 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', we should focus on some fundamental points that will help us to understand the importance of the excursus of the chapters and at the same time to better understand the essence of the decryption process of the neurological signal, already mentioned several times.

Let's start by saying that it is not so complex to make a diagnosis of 'Hemimasticatory Spasm', it is to make a differential diagnosis between Hemimasticatory and Hemifacial Spasm because it does not depend only on the nervous districts involved, but even more it is to understand the nature of the disease to address, subsequently, adequate therapy.

We should, first of all, consider movement disorders which can be defined as involuntary or abnormal movements triggered by trauma to the nerves or cranial or peripheral roots.[1] From this it is contextual to consider involuntary movements including spasms also pathologies of the Central Nervous System as well as the peripheral one. In a study by Seung Hwan Lee et al.[2] two vestibular schwannomas, five meningiomas and two epidermoid tumors were included. Hemifacial spasm occurred on the same side of the lesion in eight patients while it occurred on the opposite side of the lesion in one patient. Regarding the pathogenesis of hemifacial spasms, in six patients the vessels were found to be involved, in one patient the tumor involved the facial nerve lining, compression of the facial nerve hypervascular tumor without damage to the vessels in one patient and a huge tumor which compressed the brainstem thus involving the contralateral facial nerve in another patient. Hemifacial spasm resolved in seven patients, while in two patients with vestibular schwannoma and epidermoid tumor they improved transiently and then recurred at one month.

Therefore, the contributing causes of the central intracranial type should be kept in mind, which could be a contributory cause of facial and / or masticatory spasm, for example, cases of vestibular schwannoma and epidermoid tumors.

Vestibular and trigeminal schwannoma

Secondary hemifacial spasm due to vestibular schwannoma is very rare. A study by S Peker et al.[3] was the first reported case of hemifacial spasm responsive to gamma knife radiosurgery in a patient with intracanalicular vestibular schwannoma. Both spasm resolution and tumor growth control were achieved with a single gamma knife radiosurgery session. Control of tumor growth was achieved and there was no change in tumor volume at the last follow-up at 22 months. The hemifacial spasm completely resolved after a year. It has been reported that surgical removal of the presumably causative mass lesion is the only treatment in secondary hemifacial spasm.

Figure 1: Trigeminal scwannoma and dental maloccusion by Brandon Emilio Bertot et al.[4]

Figure 1: Trigeminal scwannoma and dental maloccusion by Brandon Emilio Bertot et al.[4]The criticism that can be made to this assertion is that in our case it is the masseter muscle is involved but this criticism is answered: If there is a hemifacial spasm from vestibular Scwannoma, could then a masticatory spasm from trigeminal Scwannoma occur? From a study by Ajay Agarwa [5] it appears that intracranial trigeminal schwannomas are rare tumors. Patients usually present with symptoms of trigeminal nerve dysfunction, the most common symptom being facial pain. MRI is the imaging modality of choice and is usually diagnostic in the appropriate clinical setting. T2-weighted 3D CISS axial sequences are important for a correct evaluation of the cisternal segment of the nerve. They are usually hypointense in T1, hyperintense in T2 with accretion after gadolinium. But we cannot be surprised if cases like the one described by Brandon Emilio Bertot et al.[4] in which a clinical case was reported of a 16-year-old boy with an atypical presentation of a large trigeminal schwannoma, dental malocclusion, painless and unilateral chewing weakness. The authors confirm that this case is the first documented case in which a trigeminal schwannoma has resulted in malocclusion; it is the 19th documented case of unilateral trigeminal motor neuropathy of any etiology.

Multiple sclerosis and trigeminal reflexes

We must make a further premise concerning axonal demilienization in multiple sclerosis. From a study by Joanna Kamińska et al.[6] it appears that multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and demyelinating disease of autoimmune origin. The main agents responsible for the development of MS include exogenous, environmental and genetic factors. MS is characterized by multifocal and temporally scattered damage of the central nervous system (CNS) leading to axonal damage. Among the clinical courses of MS we can distinguish relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPSM), primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) and relapsing progressive multiple sclerosis (RPMS). Depending on the severity of the signs and symptoms, MS can be described as benign MS or malignant MS. Diagnosis of MS is based on McDonald's diagnostic criteria, which link clinical manifestation with characteristic lesions demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and visual evoked potentials.

It should be emphasized that despite the enormous progress in MS and the availability of different diagnostic methods, this disease still represents a diagnostic challenge. It may result from the fact that MS has a different clinical course and a single test is missing, which would be of appropriate diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for rapid and accurate diagnosis.

Precisely in reference to this last observation we must point out another significant data that emerged from a study by S K Yates and W F Brown[7] in which we read that the jaw jerk of the masseter is present in all control subjects but commonly absent in patients with sclerosis. multiple defined (SM). In some MS patients, the latency was prolonged. Abnormalities in jaw jerk, however, are less common than blink reflex responses to supraorbital nerve stimulation. However, there have been patients in whom the reflex blinks were normal but the jaw jerk responses were abnormal. The latest observation suggests that jaw jerk may occasionally be useful in detecting brain stem injury in MS.

But at this point the doubt becomes reality in the sense: what should we think of the anomalies of the trigeminal reflexes highlighted in our Mary Poppins? Could we be facing a form of 'Multiple Sclerosis? How do we distinguish the location of any demienization, Central or Peripheral in the trigeminal nervous system?

Pleomorphic adenoma

Pleomorphic adenoma is a common benign neoplasm of the salivary glands characterized by the neoplastic proliferation of epithelial (ductal) cells together with myoepithelial components, with malignant potential. It is the most common type of salivary gland tumor and the most common parotid gland tumor. It derives its name from the architectural Pleomorphism (variable aspect) seen under the optical microscope. It is also known as a "mixed tumor, salivary gland type", which refers to its dual origin from epithelial and myoepithelial elements in contrast to its pleomorphic appearance.

The diagnosis of salivary gland tumors uses both tissue sampling and radiographic studies. Tissue sampling procedures include fine needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy (needle larger than FNA). Both of these procedures can be performed on an outpatient basis. Imaging techniques for salivary gland tumors include ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT allows direct bilateral visualization of salivary gland tumor and provides information on overall size and tissue invasion. CT is excellent for demonstrating bone invasion. MRI provides superior soft tissue delineation such as perineural invasion compared to CT alone as well described by Mehmet Koyuncu et al.[8]

This last observation is very important because an invasion of the tumor of the nervous tissues in the infratemporal fossa cannot be excluded and precisely because of the complexity of the disease we report a work by Rosalie A Machado et al.[9] which can be deepened in the sub-chapter of Masticationpedia ' Intermittent facial spasms as the presenting sign of a recurrent pleomorphic adenoma 'in which the authors confirm that to date the development of facial spasms has not been reported in parotid neoplasms. The most common etiologies for hemifacial spasm are vascular compression of the facial nerve ipsilateral to the cerebellopontine angle (defined as primary or idiopathic) (62%), hereditary (2%), secondary to Bell's palsy or facial nerve injury (17 %) and imitators of hemifacial spasms (psychogenic, tics, dystonia, myoclonus, myochemia, myorhythmias and hemimasticatory spasm) (17%).

Scleroderma

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma, SSc) is a rare multisystem autoimmune disease characterized by autoantibodies, vasculopathy, and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs but a systematic review of neurological involvement in systemic sclerosis (SSc) and localized scleroderma (LS) but is useful, describing the clinical features, neuroimaging and treatment.

A study by Tiago Nardi Amaral et al.[10] in a PubMed literature search using the following terms MeSH, scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, localized scleroderma, localized scleroderma "en coup de saber", Parry-Romberg syndrome, cognitive impairment, memory, seizures, epilepsy, headache, depression, anxiety, mood disorders, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D), SF-36, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), neuropsychiatry, psychosis , neurological involvement, neuropathy, peripheral nerves, cranial nerves, carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar entrapment, tarsal tunnel syndrome, mononeuropathy, polyneuropathy, radiculopathy, myelopathy, autonomic nervous system, nervous system, electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) came to the following conclusions: A total of 182 case reports / studies were identified regarding SSc and 50 referred to LS.

In LS, seizures (41.58%) and headache (18.81%) predominated. However, descriptions of various cranial nerve and hemiparesis involvement have been made. Central nervous system involvement in the SSC was characterized by headache (23.73%), seizures (13.56%) and cognitive impairment (8.47%). Depression and anxiety were frequently observed (73.15% and 23.95%, respectively). Myopathy (51.8%), trigeminal neuropathy (16.52%), peripheral sensorimotor polyneuropathy (14.25%) and carpal tunnel syndrome (6.56%) were the most frequent involvement of the peripheral nervous system in the SSc.

But this is not all because there are some variants of scleroderma such as Morphea.

Morphea

Morphea is a form of scleroderma that presents with isolated patches of hardened skin on the face, hands and feet or anywhere else on the body, without involvement of internal organs. Morphea most often occurs as macules or plaques a few centimeters in diameter, but can also appear as bands or in guttate lesions or nodules. [11]Morphea is a thickening and hardening of the skin and subcutaneous tissues due to the excessive deposition of collagen .

Morphea encompasses specific conditions ranging from very small plaques that involve only the skin to widespread diseases that cause functional and aesthetic deformities. Morphea differs from systemic sclerosis by its presumed lack of involvement of internal organs.[12]

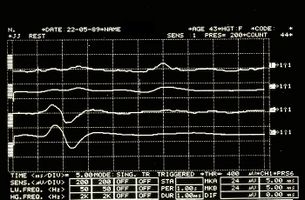

Unfortunately the path is still difficult because the long series of variants does not exclude a form of 'Hemimasticatory spasm' from Morfea as well described by H J Kim et al.[13] in which it is asserted that on the basis of clinical and electrophysiological trigeminal results such as blink reflex, jaw jerk and the masseterine silent period, focal demyelination of the motor branches of the trigeminal nerve due to alterations of the deep tissues is suggested as a cause of electrical activity abnormal excitatory movements resulting in involuntary masticatory movement and spasm.

The latter assertion indicates an involvement of physiological and emphatic excitatory electrical activities.

Conclusions

Before describing the pathways implemented to reach the diagnosis of our poor patient Mary Poppins of 'Hemimasticatory Spasm' we should anticipate that the encrypted code, considered a 'communication phenomenon' refers to a neurophysiopathological phenomenon called 'Hephaptic transmission', a very important phenomenon and complex to evoke, but above all it requires a description of a topic that is sometimes taken for granted that of 'electrical transmission between neurons'.

Electrical signaling is a key feature of the nervous system and gives it the ability to react quickly to changes in the environment. Although synaptic communication between nerve cells is perceived primarily as chemically mediated, electrical synaptic interactions also occur. Two different strategies are responsible for the electrical communication between neurons. One is the consequence of low resistance intercellular pathways, called “gap junctions”, for the diffusion of electric currents between the inside of two cells. The second occurs in the absence of cell-to-cell contacts and is a consequence of the extracellular electric fields generated by the electrical activity of neurons.

In the chapter dedicated to this fundamental topic (Two Forms of Electrical Transmission Between Neurons), the current notions of electrical transmission from a historical perspective will be discussed by comparing the contributions of the two different forms of electrical communication to brain function.

- ↑ Jankovic J, «Peripherally induced movement disorders», in Neurol Clin, 2009».

PMID:19555833

DOI:10.1016/j.ncl.2009.04.005 - ↑ Lee SH, Rhee BA, Choi SK, Koh JS, Lim YJ, «Cerebellopontine angle tumors causing hemifacial spasm: types, incidence, and mechanism in nine reported cases and literature review», in Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2010».

PMID:20845049

DOI:10.1007/s00701-010-0796-1 - ↑ Peker S, Ozduman K, Kiliç T, Pamir MN, «Relief of hemifacial spasm after radiosurgery for intracanalicular vestibular schwannoma», in Minim Invasive Neurosurg, Georg Thieme Verlag, 2004, Stuttgart · New York».

DOI:10.1055/s-2004-818485 - ↑ 4.0 4.1 Brandon Emilio Bertot, Melissa Lo Presti, Katie Stormes, Jeffrey S Raskin, Andrew Jea, Daniel Chelius, Sandi Lam. Trigeminal schwannoma presenting with malocclusion: A case report and review of the literature.Surg Neurol Int. 2020 Aug 8;11:230. doi: 10.25259/SNI_482_2019.eCollection 2020.

- ↑ Ajay Agarwal. Intracranial trigeminal schwannoma Ajay Agarwal. Neuroradiol J.2015 Feb;28(1):36-41. doi: 10.15274/NRJ-2014-10117.

- ↑ Joanna Kamińska, Olga M Koper, Kinga Piechal, Halina Kemona . Multiple sclerosis - etiology and diagnostic potential.Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2017 Jun 30;71(0):551-563.doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3836.

- ↑ S K Yates, W F Brown. The human jaw jerk: electrophysiologic methods to measure the latency, normal values, and changes in multiple sclerosis.Neurology. 1981 May;31(5):632-4.doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.5.632.

- ↑ Mehmet Koyuncu, Teoman Seşen, Hüseyin Akan, Ahmet A Ismailoglu, Yücel Tanyeri, Atilla Tekat, Recep Unal, Lütfi Incesu. Comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of parotid tumors.Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Dec;129(6):726-32.doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.07.009.

- ↑ . 2017 Feb 10;8(1):86-90. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.86. Rosalie A Machado, Sami P Moubayed, Azita Khorsandi, Juan C Hernandez-Prera, Mark L Urken. Intermittent facial spasms as the presenting sign of a recurrent pleomorphic adenoma. World J Clin Oncol. 2017 Feb 10;8(1):86-90. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.86.

- ↑ Tiago Nardi Amaral, Fernando Augusto Peres, Aline Tamires Lapa, João Francisco Marques-Neto, Simone Appenzeller. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma: a systematic review Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Dec;43(3):335-47. doi: 10.1016/ j.semarthrit. 2013.05.002. Epub 2013 Jul 1.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 171. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 171. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ H J Kim, B S Jeon, K W Lee. Hemimasticatory spasm associated with localized scleroderma and facial hemiatrophy.Arch Neurol. 2000 Apr;57(4):576-80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.4.576.

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system