Physiologische Dynamik bei demyelinisierenden Krankheiten: Enträtseln komplexer Zusammenhänge durch Computermodellierung

| Title | Physiologische Dynamik bei demyelinisierenden Krankheiten: Enträtseln komplexer Zusammenhänge durch Computermodellierung |

| Authors | Jay S. Coggan · Stefan Bittner · Klaus M. Stiefel · Sven G. Meuth · Steven A. Prescott |

| Source | Document |

| Date | 2021 |

| Journal | Int J Mol Sci. |

| DOI | 10.3390/ijms160921215 |

| PUBMED | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4613250/#!po=53.5714 |

| PDF copy | |

| License | CC BY |

| This resource has been identified as a Free Scientific Resource, this is why Masticationpedia presents it here as a mean of gratitude toward the Authors, with appreciation for their choice of releasing it open to anyone's access | |

This is free scientific content. It has been released with a free license, this is why we can present it here now, for your convenience. Free knowledge, free access to scientific knowledge is a right of yours; it helps Science to grow, it helps you to have access to Science

This content was relased with a 'CC BY' license.

You might perhaps wish to thank the Author/s

Physiologische Dynamik bei demyelinisierenden Krankheiten: Enträtseln komplexer Zusammenhänge durch Computermodellierung

Free resource by Jay S. Coggan · Stefan Bittner · Klaus M. Stiefel · Sven G. Meuth · Steven A. Prescott

|

Physiological Dynamics in Demyelinating Diseases: Unraveling Complex Relationships through Computer Modeling

Jay S. Coggan, Stefan Bittner, [...], and Steven A. Prescott

Additional article information

Abstrakt

Trotz intensiver Forschung stehen für die meisten neurologischen Erkrankungen nur wenige Behandlungen zur Verfügung. Demyelinisierende Erkrankungen sind keine Ausnahme. Dies ist vielleicht nicht überraschend angesichts der multifaktoriellen Natur dieser Krankheiten, die komplexe Wechselwirkungen zwischen Zellen des Immunsystems, Glia und Neuronen umfassen. Bei Multipler Sklerose zum Beispiel herrscht unter Forschern Uneinigkeit über die Ursache oder gar welches System oder welcher Zelltyp Ground Zero sein könnte. Diese Situation schließt die Entwicklung und strategische Anwendung mechanismusbasierter Therapien aus. Wir werden diskutieren, wie Computermodellierung, die auf Fragen auf verschiedenen biologischen Ebenen angewendet wird, dabei helfen kann, unterschiedliche Beobachtungen miteinander zu verknüpfen und komplexe Mechanismen zu entschlüsseln, deren Lösungen einem einfachen Reduktionismus nicht zugänglich sind. Indem sie überprüfbare Vorhersagen treffen und kritische Lücken im vorhandenen Wissen aufdecken, können solche Modelle die Forschung unterstützen und einen rigorosen Rahmen bieten, in den neue Daten integriert werden können, sobald sie gesammelt werden. Heutzutage gibt es keinen Mangel an Daten; Die Herausforderung besteht darin, dem Ganzen einen Sinn zu geben. In dieser Hinsicht ist die Computermodellierung ein unschätzbares Werkzeug, das letztendlich unser Verständnis, die Diagnose und Behandlung von demyelinisierenden Krankheiten verändern könnte.

Schlüsselwörter: Myelin, Demyelinisierung, Multiple Sklerose, neurodegenerative Erkrankung, Computermodell, Wirkstoffforschung

Einführung

Die Nervensysteme von Wirbeltieren werden aufgrund ihres Aussehens und der entsprechenden funktionellen Rollen oft in graue und weiße Substanz unterteilt. Während die graue Substanz größtenteils aus Zellkörpern und Dendriten besteht, enthält die weiße Substanz hauptsächlich Axone und hat ihren Namen von den Lipidmembranschichten namens Myelin, die eng um diese Axone gewickelt sind.[1] Myelin stammt aus verschiedenen Klassen von Gliazellen, die als Oligodendrozyten im Zentralnervensystem (ZNS) und Schwann-Zellen im peripheren Nervensystem (PNS) bezeichnet werden.

Die durch die Myelinschichten bereitgestellte elektrische Isolierung verbessert die axonale Funktion, indem sie sowohl die Energieeffizienz als auch die Leitungsgeschwindigkeit von Aktionspotentialen (APs) erhöht. Diese beiden Funktionen haben möglicherweise ihre relative Bedeutung während der Evolution geändert.[2] Myelin tauchte erstmals im Ordovizium (485 bis 443 ma oder Millionen Jahre vor der Gegenwart) auf, nachdem sich die Vorfahren der Neunaugen und Schleimaale von den übrigen Wirbeltierlinien abgespalten hatten.[3]Mit einigen interessanten Ausnahmen,[4][5] Myelin oder analoge Strukturen kommen in allen Wirbeltieren vor und sind entscheidend für das reibungslose Funktionieren ihres Nervensystems. Der ungefähre Zeitpunkt der Entwicklung von Myelin kann aus der bekannten Zeit der Divergenz zwischen Akkordaten ohne (Agnatha) und mit (alle anderen Wirbeltiere) Myelin abgeleitet werden.

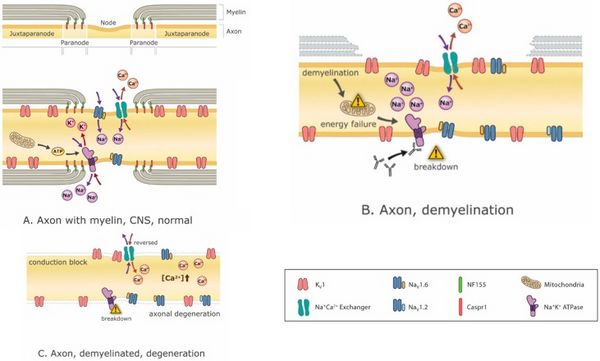

Die Myelinumhüllung wird durch regelmäßig beabstandete, nicht myelinisierte Abschnitte unterbrochen, die als Ranvier-Knoten bekannt sind. Myelin beschleunigt die Leitung, indem es den transmembranen Ladungsfluss durch Ionenkanäle innerhalb der Knoten einschränkt. Innerhalb der sogenannten Internodien fließt Strom das Axon hinunter, wobei nur wenig davon durch die isolierte Zellmembran fließt. Das AP wird an jedem Knoten regeneriert, an dem die Dichte der spannungsgesteuerten Natrium- und Kaliumkanäle sehr hoch ist. Dieser Vorgang wird als „saltatorische Leitung“ bezeichnet, da der AP scheinbar von Knoten zu Knoten springt. Störungen in diesem Schnellfeuer-Kommunikationssystem können mit einer Reihe von Funktionsstörungen des Nervensystems in Verbindung gebracht werden.[6]

Axone scheinen in mehrfacher Hinsicht an physikalischen Grenzen zu operieren. Ein interessantes Beispiel ist, dass die Größe von Axonen durch das thermische Rauschen beschränkt zu sein scheint, das Ionenkanalproteinen innewohnt; Jedes Axon, das dünner als 0,1 μm ist, wäre aufgrund seines hohen Rauschpegels für die Informationsübertragung unbrauchbar.[7] Interessanterweise ist 0,1 μm auch ungefähr der kleinste Axondurchmesser, der in Nervensystemen beobachtet wird [7]. Diese und ähnliche Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass Axone und ihre Unterstrukturen fein abgestimmte biologische Geräte sind, dass die Abstimmung jedoch offensichtlich unter pathologischen Bedingungen gestört werden kann.[8]

Die Demyelinisierung setzt funktionelle Veränderungen in Gang, die für klinische Merkmale wichtig sind, aber nicht ohne weiteres durch immunologische oder radiologische Veränderungen erklärt werden können. Die Lage einer Plaque sagt voraus, welches System betroffen sein wird (motorisch vs. sensorisch, visuell vs. taktil), aber nicht, wie es betroffen sein wird. Dies unterstreicht die Bedeutung der Beurteilung der Funktion (zusätzlich zur Struktur) und wie sie sich nach der Demyelinisierung verändert. Nach der Einführung demyelinisierender Krankheiten werden wir erörtern, wie die klinischen Manifestationen dieser Krankheiten verschiedene pathologische Veränderungen der Axonfunktion widerspiegeln. Wir werden argumentieren, dass das Verständnis dieser Veränderungen und die vollständige Nutzung dieses Verständnisses für diagnostische und therapeutische Zwecke enorm von der Computermodellierung profitieren können.

Demyelinisierende Krankheiten

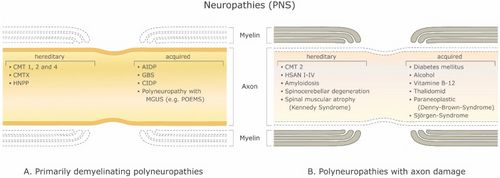

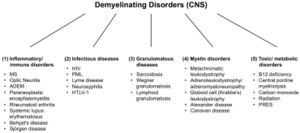

Es gibt eine große Anzahl demyelinisierender Erkrankungen, die sowohl das PNS (Abbildung 1) als auch das ZNS (Abbildung 2) betreffen. Die Ätiologien sind heterogen und reichen von genetischen Störungen bis hin zu metabolischen, infektiösen oder Autoimmunmechanismen. Multiple Sklerose (MS) ist mit schätzungsweise 3 Millionen Patienten weltweit die am weitesten verbreitete dieser Erkrankungen. Die zugrunde liegende Ursache ist ungewiss, es wird jedoch angenommen, dass sie eine genetische Veranlagung für Umwelteinflüsse beinhaltet[9][10]und kann immunologische, Reaktionsfähigkeit auf Traumata, biophysikalische, genetische und/oder metabolische Komponenten umfassen.[10]Die Symptome und Läsionen müssen zeitlich und räumlich vielfältig sein. Das heißt, es müssen zeitlich mehrere Episoden auftreten, an denen getrennte Teile des zentralen Nervensystems beteiligt sind. Es ist nicht klar, ob die entzündliche Demyelinisierung ein primäres oder sekundäres Ereignis innerhalb des Krankheitsprozesses ist.[9][11][12] Die meisten Behandlungen zielen auf das Immunsystem oder die Blut-Hirn-Schranke ab, aber auch die Behandlung neurologischer Symptome durch Modulation der axonalen Erregbarkeit spielt eine wichtige Rolle (siehe unten)..

Klinische Bewertung von Multipler Sklerose

Die Symptome sind vielfältig und können bei einem einzelnen Patienten in allen Kombinationen auftreten. Die Diagnose erfordert, dass im Laufe der Zeit mehrere Läsionen und symptomatische Episoden vorliegen müssen, an denen nicht verbundene Teile des ZNS beteiligt sind. Darüber hinaus neigen die Symptome dazu, schlecht mit radiologischen Messungen zu korrelieren. In den allermeisten Fällen korrelieren individuelle klinische Merkmale nicht gut mit MRT-Befunden, insbesondere bei zerebralen Läsionen.[13][14][15] Diese klinisch-radiologische Dissoziation verlangt nach einem besseren theoretischen Verständnis der Demyelinisierungssymptome und der zugrunde liegenden biophysikalischen Veränderungen, die sie begleiten, was natürlich die Frage aufwirft, was genau mit den betroffenen Axonen passiert.

Die Symptome sind oft intermittierend und können sowohl Funktionsverlust (negative Symptome wie Taubheitsgefühl, Muskelschwäche, Kribbeln, Blindheit, Inkontinenz, Verlust der Sexualfunktion, Gleichgewichtsverlust, undeutliche Sprache, Verstopfung, beeinträchtigende Müdigkeit, Depression, kognitive Dysfunktion) umfassen , Unfähigkeit zu schlucken, Gangstörungen und Verlust der Atemkontrolle) und Funktionsgewinn (unter anderem positive Symptome wie Krämpfe, Spastik, Krämpfe, Schmerzen, verschwommenes oder doppeltes Sehen, Harndrang oder Zögern, Übelkeit)..[16]Frühe differenzialdiagnostische Kriterien sind das Lhermitte-Zeichen (Halsbeugegefühle) und das Uhthoff-Phänomen (temperaturabhängige Verschlechterung der Beschwerden). Die Differenzialdiagnose der MS richtet sich eng nach den McDonald-Kriterien.[17]

In humandiagnostischen Studien zu visuell, sensorisch oder motorisch evozierten Potentialen (VEP, SEP, MEP) kann nur die Latenz oder Leitungsgeschwindigkeit genau gemessen werden (mit etwa 30–40 % Schwankungen zwischen verschiedenen Labors). Aber diese Messungen geben wenig Aufschluss über zugrunde liegende Mechanismen, die eine Verlangsamung oder Blockierung der Leitung beinhalten, oder morphologische oder funktionelle Faktoren wie Verzweigung, Demyelinisierung, Remyelinisierung, axonale Verjüngung (Abnahme der Querschnittsfläche), Dämpfung oder erneutes Wachstum, temperaturbedingte Änderungen der Leitung , oder Malpolarisation (Hyper oder Hypo). Nichtsdestotrotz kann die Art der demyelinisierenden Läsion Hinweise auf die Ätiologie geben und daher die Behandlung leiten; Beispielsweise scheinen genetische Faktoren stärker mit internodalen Krankheitsprozessen zu korrelieren, und immunologische Dysfunktionen verursachen paranodale Anomalien.[18]

Eine Reihe von Tests werden routinemäßig verwendet, um die neurale Funktion zu beurteilen. Bei der Elektroneurographie wird ein kurzer elektrischer Stimulus an einer anatomisch vordefinierten Position an einen peripheren Nerv angelegt, um die Latenz und Amplitude des zusammengesetzten Aktionspotentials an einer anderen Stelle entlang des Nervs zu messen. Die Ergebnisse müssen in Kombination mit klinischen Befunden und Tests (z. B. Elektromyographie) interpretiert werden, aber es ist wichtig, dass verschiedene Krankheiten unterschiedliche Muster elektroneurographischer Veränderungen aufweisen. Dies ist nicht nur für diagnostische Zwecke wichtig, sondern kann auch auf spezifische pathologische Veränderungen der Axonfunktion hinweisen, die wiederum bei der Wahl der Therapie hilfreich sein könnten (wenn die Axonpathobiologie verstanden würde; siehe unten). Unter Verwendung von Threshold-Tracking wurde die Erregbarkeit beim Menschen für verschiedene periphere demyelinisierende Erkrankungen gemessen, darunter die Charcot-Marie-Tooth-Krankheit Typ 1A (CMT1A), die chronisch entzündliche demyelinisierende Polyneuropathie (CIDP), das Guillain-Barré-Syndrom (GBS) und die multifokale motorische Neuropathie (MMN). ).[19][20][21][22][23][24][25]Die Herausforderung liegt in der Interpretation dieser Beobachtungen. Zu diesem Zweck hat die Gruppe von Stephanova zunehmend größere Grade systematischer und fokaler Demyelinisierung von Motorfasern simuliert, um zu versuchen, die beobachteten physiologischen Veränderungen zu erklären[26][27][28][29][30][31] (siehe Abschnitt „Modellierung“ weiter unten).

Beteiligung von Zellkörpern

Die Progression von schubförmig remittierender MS (RRMS) zur sekundär progredienten MS (SPMS) ist mit einer stärkeren Beteiligung der Pathologie der grauen Substanz verbunden, obwohl eine Beteiligung der Axone/der grauen Substanz bereits in frühen Krankheitsstadien beobachtet werden kann.[32][33][34][35] Die Schädigung der grauen Substanz gilt als zugrunde liegender Mechanismus des Krankheitsverlaufs und der dauerhaften Behinderung bei MS-Patienten und wird durch den Verlust der Hirnparenchymfraktion oder des Gehirnvolumens durch MRT oder klinisch durch Progression auf der erweiterten Behinderungsstatusskala (EDSS) gemessen.[36]Der Übergang von RRMS zu SPMS ist ein Vorzeichen für den Mangel an Therapeutika zur Bekämpfung der verschlimmerten körperlichen und kognitiven Verschlechterung, mit der die meisten SPMS-Patienten konfrontiert sind.[9][37]

Behandlung

Die wichtigsten Eingriffe bei MS umfassen die Modulation der Immunantwort mit beispielsweise Methly-Prednisolon, Interferon betas, Glatirameracetat oder Fingolimod oder die Verhinderung der Überquerung der BHS durch Entzündungszellen (monoklonale Antikörper, z. B. Tysabri (Anti-α4-Integrin, Natalizumab )). Vor kurzem wurden die ersten beiden oralen Wirkstoffe (Fumarat und Teriflunomid) sowie der gegen CD52 gerichtete Antikörper Natalizumab für die Behandlung von RRMS zugelassen, die erfolgreich mit Erstlinientherapien wie Interferonen, Glatirameracetat oder Fingolimod oder durch behandelt werden kann Zweitlinientherapien, aber progressive Formen (PPMS, SPMS) stellen immer noch einen ungedeckten biomedizinischen Bedarf dar.[38] Antineoplastika werden in extrem fortgeschrittenen oder schwierigen Fällen eingesetzt.[39]

Krankheitsmodifizierende Medikamente sind entscheidend, um den Demyelinisierungsprozess zu stoppen oder zumindest abzuschwächen, aber ebenso wichtig ist es, die Symptome zu behandeln, die sich aus einer bereits aufgetretenen Demyelinisierung ergeben. Die Ionenkanalmodulation wird mit dem Aufkommen neuer Ionenkanalblocker wie Ampyra (K-Kanal-Blockade) zunehmend vielversprechend.[40][41] Die Kaliumkanalblockade soll die Erregbarkeit von Axonen verbessern. Das Problem ist, dass solche Eingriffe, obwohl sie bei der Behandlung negativer Symptome und der Wiederherstellung der Funktion wirksam sind, dazu neigen, positive Symptome zu verschlimmern.[42] Umgekehrt kann die Behandlung positiver Symptome wie Spasmen mit Antiepileptika wie beispielsweise Carbamazepin negative Symptome verstärken.[43] Tatsächlich reduziert das Blockieren von Na+-Kanälen nicht nur positive Symptome, es kann auch neuroprotektiv sein (weil die Ansammlung von Na+ dazu führt, dass Na+/Ca2+-Austauschmechanismen Neuronen mit Ca2+ beladen, das exzitotoxisch ist).[44] (Abbildung 3), aber diese Vorteile gehen zu Lasten negativer Symptome. Daher und insbesondere bei einem Patienten, der eine Mischung aus positiven und negativen Symptomen aufweist, sind die Behandlungsmöglichkeiten eingeschränkt.

Die obige Diskussion wirft den wichtigen Punkt auf, dass, obwohl viel Lärm um Immunmechanismen gemacht wurde, ihre Verbindung mit klinischen Veränderungen weitgehend korreliert ist. Man muss die intermediären Wirkungen auf die axonale Funktion berücksichtigen, nämlich die primären und sekundären (kompensatorischen) Änderungen der Axon-Erregbarkeit, um zu verstehen, wie die neurologische Funktion verändert wird. Diese Veränderungen sind keine einfachen und direkten Folgen der Demyelinisierung, sondern legen stattdessen nahe, dass sich die axonale Physiologie selbst als Reaktion auf die Demyelinisierung verändert. Einige dieser Veränderungen sind adaptiv, während andere maladaptiv sind, oder vielleicht können adaptive Veränderungen maladaptiv werden, wenn sich die Situation (Myelinisierungsstatus) weiterentwickelt. Wenn Veränderungen in der Axonphysiologie die Manifestation verschiedener Symptome diktieren, dann wird die Symptombehandlung weitgehend auf Behandlungen fallen, die darauf abzielen, die Axonphysiologie zu manipulieren. Die strategische Entwicklung solcher Behandlungen erfordert ein tiefes, mechanistisches Verständnis der axonalen Erregbarkeit und ihrer Regulation.

Axonpathobiologie

Strukturelle und molekulare Veränderungen

Axone sind stark von Demyelinisierung betroffen. Die Axonmorphologie wird unregelmäßig oder geschwollen, oft mit einem perligen Aussehen. Eine fokale Akkumulation von Proteinen (durch schnellen axonalen Transport) wird ebenfalls beobachtet. Bei chronisch aktiven Plaques ist ein axonaler Verlust von 20–80 % in der weißen Substanz der Periplaque und in der normalen entfernten weißen Substanz erkennbar.[45] Bei früh aktiven und chronisch aktiven Plaques wird angenommen, dass die Schädigung durch Entzündungs- und Immunfaktoren verursacht wird, die während der akuten entzündlichen Demyelinisierung freigesetzt werden. Vorgeschlagene Mediatoren umfassen Proteasen, Cytokine, Excitotoxine und freie Radikale. Neuronale Antigene sind Ziele einer Immunreaktion, die zu einer ZNS-Entzündung führt. Andere Faktoren, die eine axonale Dysfunktion oder den Tod verursachen, umfassen einen Mangel an trophischer Unterstützung durch Myelin und Oligodendrozyten, Schäden durch lösliche oder zelluläre Immunfaktoren, die noch in der inaktiven Plaque vorhanden sind, und chronisches Mitochondrienversagen bei erhöhtem Energiebedarf.[46] Eine entscheidende Rolle für Oligodendrozyten und Schwann-Zellen beim Überleben von Axonen wurde auch den Peroxisomen, dem Lipidstoffwechsel und der Entgiftung reaktiver Sauerstoffspezies (ROS) zugeschrieben.[47]

Remyelinisierung wird häufig als Schattenplaques beobachtet, die durch die Rekrutierung von undifferenzierten Oligodendrozyten-Vorläufern gebildet werden, die zu den Läsionen wandern und diese umgeben, wodurch dünne Schichten der Remyelinisierung ermöglicht werden.[48] Dieser Prozess tritt meist in akuten aktiven Plaques auf, aber auch in chronischen Phasen. Diese Beobachtung löste die Entwicklung eines neuen monoklonalen Antikörpers aus, der gegen LINGO-1 gerichtet ist (Anti-LINGO-1). Die Bindung von LINGO-1 an Nogo-Rezeptoren verhindert remyelinisierende Prozesse im ZNS; die Hemmung dieser Wechselwirkung ermöglicht somit eine signifikante Remyelinisierung bei Tieren mit experimenteller autoimmuner Enzephalomyelitis.[49]

Während des Krankheitsprozesses können autoreaktive Lymphozyten und Makrophagen die Blut-Hirn-Schranke überwinden und sich im Gehirn und Rückenmark ansammeln.[50] Regulatorische Lymphozyten (Tregs) unterdrücken Effektorzellen nicht – meist zytotoxische CD8+-Zellen.[51] Die Freisetzung von entzündungsfördernden Zytokinen rekrutiert naive Mikroglia, die durch Wechselwirkungen mit Fc- und Komplementrezeptoren Kontakt mit einer Oligodendrozyten-Myelin-Einheit aufnehmen. Ein zytotoxisches, den Tod auslösendes Signal wird dann durch den oberflächengebundenen Tumornekrosefaktor α (TNFα) übertragen..[52] Dies tritt zusammen mit ausgedehnten axonalen Schäden auf.[10]

Lucchinetti el al.[46]schlugen vier unterschiedliche Immunmuster der Plaquebildung vor, die bei Patienten in verschiedenen Stadien der Krankheit gefunden wurden. Plaques vom Typ I und II werden von T-Lymphozyten- und Makrophagen-Entzündungen dominiert und es wird angenommen, dass sie T-Zell- bzw. T-Zell-plus-Antikörper-Autoimmun-Enzephalomyelitis-Modelle nachahmen. Myelinverlust in Typ-I-Plaques kann durch toxische Faktoren verursacht werden, die von aktivierten Makrophagen freigesetzt werden, während IgG- und Komplementablagerung auf eine Rolle von Antikörpern in Typ-II-Plaques hindeuten. Im Gegensatz dazu zeigen die Muster III und IV eine große Oligodendrozyten-Dystrophie. Es wird angenommen, dass Muster III mit Hypoxie-induzierten Läsionen zusammenhängt, die durch Defekte in der mitochondrialen Funktion verursacht werden,[53] wohingegen Muster-IV-Läsionen mit tiefgreifendem nicht-apoptotischem Tod von Oligodendrozyten in der weißen Substanz der Periplaque assoziiert sind.

Barnett and Prineas[54] analysierten Läsionen von Patienten direkt nach dem Einsetzen eines Rezidivs, während dessen eine aktive Plaquebildung andauerte. Ihre Ergebnisse legen nahe, dass Oligodendrozyten-Apoptose und Glia-Aktivierung während der frühen aktiven Plaquebildung in Abwesenheit von entzündlichen Lymphozyten oder Myelin-Phagozyten auftreten. Sie schlugen vor, dass die Anfälligkeit von Oligodendrozyten, die in Lucchinettis Typ-III-Muster beschrieben wird, in den frühen Stadien aller Plaquebildung vorhanden ist und der Auslöser für die nachfolgende postapoptotische Nekrose ist, die in späteren Stadien die Phagozytose von Myelin durch Makrophagen einleitet. In-vitro-Analysen dieses Prozesses haben Komplementkaskaden, Tumornekrosefaktoren oder gasförmige Second Messenger impliziert.[55]Obwohl die Identifizierung von Plaques und die Überwachung ihres Fortschritts einen wichtigen klinischen Wert haben, gibt es nur eine bescheidene Korrelation zwischen der Belastung durch demyelinisierende Läsionen, wie sie durch herkömmliches MRI bestimmt wird, und der klinischen Behinderung von Patienten mit MS (siehe oben).

Funktionale Änderungen

Zu den Mechanismen der funktionellen Beeinträchtigung während der Demyelinisierung gehören häufig die Störung der transmembranen Na+-, K+- und Ca2+-Ionen, die Ausbreitung ihrer entsprechenden Ionenkanäle, eine Abnahme der Effizienz der AP-Leitung und eine daraus resultierende Stoffwechselkrise (Abbildung 3). Eine Demyelinisierung kann leicht einen Leitungsausfall innerhalb des betroffenen Axons erklären. Wenn die Leitung nicht vollständig ausfällt, kann die Leitungsgeschwindigkeit dennoch verlangsamt werden, und eine unterschiedliche Verlangsamung über verschiedene Axone kann variable Leitungsverzögerungen verursachen, die zu einem desynchronisierten Spiking führen.

Die Demyelinisierung ermöglicht auch, dass entblößte Axone eng aneinander liegen, wodurch die Voraussetzungen für ephaptische Wechselwirkungen und Übersprechen geschaffen werden.[10] Eine Reflexion kann auch aufgrund einer Impedanzfehlanpassung zwischen myelinisierten und nicht myelinisierten Axonlängen auftreten. Andererseits kann Übererregbarkeit nicht direkt der Demyelinisierung zugeschrieben werden; Stattdessen müssen sekundäre Veränderungen der intrinsischen Erregbarkeit herangezogen werden, um Phänomene wie die Erzeugung ektopischer Spitzen und Nachentladung (AD) zu erklären. Veränderungen der Erregbarkeit stellen wahrscheinlich kompensatorische Veränderungen dar, die darauf abzielen, die Funktion nach der direkt durch Demyelinisierung verursachten Störung wiederherzustellen, was mit einem Prozess übereinstimmt, der als homöostatische Plastizität bezeichnet wird,[56] aber diese Kompensation kann offensichtlich maladaptiv sein. Jedes der oben genannten Ergebnisse, die sich nicht gegenseitig ausschließen, trägt dazu bei, unterschiedliche Symptome hervorzurufen, die bei demyelinisierenden Erkrankungen beobachtet werden.

Paroxysmale Symptome, die durch das plötzliche Einsetzen oder Verstärken von Symptomen wie Spasmen oder stechenden Schmerzen gekennzeichnet sind, entstehen wahrscheinlich durch AD oder anderweitig unangemessenes Spiking vom Burst-Typ. Solche Spiking-Muster legen hochgradig nichtlineare Wechselwirkungen zwischen dem beitragenden Ionenstrom nahes[57][58] and could, in theory at least, involve interactions between different regions of the neuron.[59] Im Gegensatz zu allgemeineren Formen der Übererregbarkeit (z. B. erhöhte Feuerrate oder reduzierte Schwelle) sind diese spezifischen Muster in Bezug auf die genauen Mechanismen, durch die sie entstehen können, begrenzt. Daher kann die Identifizierung der Ionenkanalveränderungen, die diesen spezifischen Formen der Übererregbarkeit zugrunde liegen, dazu beitragen, die Suche nach Ionenkanalveränderungen einzuschränken, die für assoziierte, jedoch weniger ausgeprägte Formen der Übererregbarkeit verantwortlich sind.

Die Störung des Energiegleichgewichts in einem Neuron könnte sich auch tiefgreifend auf das Wohlbefinden des Neurons auswirken (Abbildung 3). Tatsächlich können kompensierende Änderungen gewisse Funktionen wiederherstellen, aber ohne das Hauptproblem umzukehren, können andere Probleme auftreten. Selbst wenn zum Beispiel ein Leitungsblock durch eine geeignete kompensierende Änderung der Erregbarkeit verhindert wird (d. h. eine, die nicht zu einer Übererregbarkeit führt), kann das System weniger energieeffizient sein. Der Verlust der Energieeinsparungen durch Saltatorische Leitung induziert eine kompensatorische mitochondriale Energieproduktion, die zu oxidativen Schäden und Neurodegeneration führen kann.[53][60][61]

Es ist keine leichte Aufgabe, diese lange Liste neurobiologischer Veränderungen im Auge zu behalten, die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen diesen Veränderungen zu verstehen und diese Veränderungen letztendlich mit klinischen Manifestationen zu verknüpfen und eine wirksame Behandlung anzuwenden. Zu diesem Zweck ist die computergestützte Modellierung ein unschätzbares Werkzeug. Simulationen dienen nicht nur dazu, bereits bekannte Informationen zu organisieren, sondern identifizieren auch entscheidende Wissenslücken. Die vernünftige Verwendung von Computermodellen kann daher ein umfassenderes Verständnis ermöglichen und die effektivere Anwendung dieses Verständnisses erleichtern, wie unten erörtert.

Computational Modeling

Especially when paired with traditional experiments, computational modeling is indispensable for making sense of inconsistent data and complex mechanisms. These benefits are exemplified by the application of simulations in other fields, such as epilepsy.[62] Here we survey some of the history of computational modeling of axons, ion conductances, the physiology of myelin and demyelination, the immune system, mitochondria and other biological factors that are critical for understanding demyelinating diseases. Our review is not exhaustive but will provide a broad introduction to past, present, and future efforts in this area.

Modeling Axons

The computational modeling of axons has evolved taxonomically, from squid to mammalian tissues with a corresponding increase in sophistication. The Hodgkin and Huxley (HH) model, which provided the first thorough explanation of AP generation, was derived from experiments in unmyelinated giant axons of squid,[63][64] but this early model has proven to be an invaluable tool from which later, more sophisticated models of myelinated axons have evolved.

The spatial and biophysical heterogeneity conferred by the addition of myelin, and the consequent formation of nodes and internodal regions, represents a significant increase in axon complexity. The first computational model of a myelinated axon was a one-dimensional model that collapsed the myelin sheath into the underlying passive axolemma, used a uniform spatial step size to form the discrete approximation used in the numerical solution and employed a HH characterization of the nodal membrane.[65] Goldman & Albus[66] modified this model to include a description of the nodal membrane derived from experimental data on Xenopus laevis myelinated nerve fibers as determined by Frankenhaeuser & Huxley.[67] Subsequent studies have used the same basic form for the model with some variations for the representation of the axolemma.[15][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76] The single cable model, describing the axon and all of its conductance and capacitance properties in one cable equation, has dominated the field until the present day despite the introduction of double cable models by Blight.[77] In double cable models, the internodal axolemma and the myelin sheath are independently represented. The double cable model has been expanded by Halter and Clark[78] to explore effects of the complex geometry of CNS oligodendrocytes (or Schwann cells in the case of the PNS).

Newer models have also improved upon previous simplifications including the anatomical complexity of the node of Ranvier, the distribution of ionic channels in the axon beneath the myelin sheath, the different electrical properties of the myelin sheath and the axolemma, and accommodation of possible current flow within the periaxonal space.[78][79][80][81][82] Anatomical representations of the paranodal area have allowed more detailed assessment of the effects of traumatic brain injury (TBI) on myelinated axons.[83] One of the most anatomically sophisticated models includes representation of the complex aqueous sheath structure of myelin lamellae as a series of interconnecting parallel lamellae in a model of motor nerves.[30][80]

Newer models have also considered the non-uniform distribution of ion channels throughout the axon [19,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].[19][84][85][86][87][88][89][90] Beyond ion channels, energy-dependent pumps and other ion-transport mechanisms provide important therapeutic targets for a number of neurological disorders.[91][92][93] In that respect, regulating transmembrane ion gradients costs significant energy and itself becomes an important consideration (see below).[94] This is especially true since the small volume of axons renders them prone to ion concentration changes that can dramatically impact driving forces, and can become problematic in models that assume constant intracellular and extracellular concentrations. But recent models have also dealt with such issues (see below).

All of the aforementioned models focus on simulating the change in axon membrane potential but one does not necessarily have experimental access to that variable, which of course complicates efforts to compare simulation and experimental data. Indeed, since extracellular recordings are the primary source of electrophysiological data from human subjects, the mathematical description of the extracellular field potential is of great interest clinically. Mathematical evaluations based on Laplace equations and Fourier transforms are used for calculating these potentials (sometimes referred to as line-source modeling, e.g.,.[82][95]

Modeling Specific Mechanisms

Beyond modeling normal axonal function, models can be used to explore particular mechanisms of axonal dysfunction especially when combined with experimental results that might better pinpoint mechanisms.[96] For example, Barrett and Barrett[97] showed that the depolarizing afterpotential (DAP) is sensitive to changes in conductance densities and capacitative changes that might occur during demyelination. A model by Blight was designed for simulation of his experimental recording conditions[77][98] and represents a single internode with multiple discrete segments and adjacent nodes and internodes in single lumped-parameter segments. This model included K+ channels in the axolemma of the single multi-segmented internode and treats the remainder as purely passive.

Building on this work, with careful attention to anatomical and electrophysiological details, McIntyre et al.[81] addressed the role of the DAP and afterhyperpolarization (AHP) in the recovery cycle—the distinct pattern of threshold fluctuation following a single action potential exhibited by human nerves. The simulations suggested distinct roles for active and passive Na+ and K+ channels in both afterpotentials and proposed that differences in the AP shape, strength-duration relationship, and the recovery cycle of motor and sensory nerve fibers can be attributed to kinetic differences in nodal Na+ conductances. Richardson et al.[99] also found that alteration to the standard “perfect insulator” model is necessary to reproduce DAPs during high-frequency stimulation.

The temperature sensitivity of demyelination effects has also been investigated computationally. Zlochiver[100] modeled persistent resonant reflection across a single focal demyelination plaque and found that this effect was sensitive to temperature and axon diameter. All of these examples demonstrated the power of simulations to examine specific mechanisms to explain observed phenomena from the clinic and offer guidance for future research.

As mentioned above, distinct changes in axon function are likely to manifest certain gain- or loss-of-function symptoms. If one could reproduce those changes in a computational model, the necessary parameter changes needed to convert the model between normal and abnormal operation could be used to predict the underlying pathology. Ideally this can lead to specific experiments in which the suspect ion channel, for example, is directly manipulated to see if its acute alteration is sufficient to reproduce or reverse certain pathological changes. Recent studies from the Prescott lab illustrate this process.[101][102] This success of these studies depended on advanced techniques including the dynamic clamp technique, used to switch between normal and abnormal spiking patterns and optogenetic tools. The next step is to link changes in axon function with disease symptoms (or their behavioural correlates in animal models).

In auditory nerve experiments, Tagoe and colleagues[103] demonstrated that hearing loss related to morphological changes at paranodes and juxtaparanodes, including the elongation of the auditory nerve around nodes of Ranvier, can result from exposure to lound noise, Extending this work, Hamann and collegues built a computational model to examine possible mechanisms. Their model suggested that it is more likely that a decrease in the density of Na-channels, rather than a redistribution of Na or K channels in general, is responsible for the conduction inhibition associated with acoustic over-exposure.[104] This experiment-model tandem demonstrates the revelatory potential of pairing computational models with laboratory experiments.

With a myelinated axon multi-layered model Stephanova and colleagues have had on-going success identifying likely anatomical and physiological deficiencies underlying various symptoms and conditions related to demyelination by making comparisons to the threshold tracking measurements from patients including latencies, refractoriness (the increase in threshold current during the relative refractory period), refractory period, supernormality, and threshold electrotonus values including stimulus-response measures such as current-threshold relationships.[21] For example, they found that mild internodal systematic demyelination (ISD) is a specific indicator for CMT1A. Mild paranodal systematic demyelination (PSD) and paranodal systematic demyelination (PISD) are specific indicators for CIPD and its subtypes. Severe focal demyelinations, internodal and paranodal, paranodal-internodal (IFD and PFD, PIFD) are specific indicators for acquired demyelinating neuropathies such as GBS and MMN [18] (see Figure 1).

Mild systematic and severe focal demyelination correspond to hereditary (CMT1A) and acquired (CIDP, GBS and MMN) neuropathies (Table 1). It was also found that 70% systematic demyelination is insufficient to cause symptoms and 96% is required for conduction block at a single node [18]. Thus, there is a large safety factor for focal demyelination. With their temperature-dependent version of the model of the myelinated human motor nerve fiber, Stephanova and Daskalova[105] showed that the electrotonic potentials in patients with CIDP are in high risk for blocking during hypo- and even mild hyperthermia and suggest mechanisms involving increased magnitude of polarizing nodal and depolarizing internodal electrotonic potentials, inward rectifier K+ and leak K+ currents increase with temperature, and the accommodation to long-lasting hyperpolarization is greater than to depolarization.

| Table 1

Correspondence between types of demyelination and diseases according to Stephanova and Dimitrov.[18] | |

|---|---|

| Type of Demyelination | Corresponding Disease (PNS) |

| Internodal systematic demyelination (ISD) | Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A (CMT1A) |

| Paranodal systematic demyelination (PSD) | Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) |

| Paranodal + internodal demyelination (PISD) | Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIPD) subtypes |

| Internodal focal demyelination (IFD) | Guillain-Barré (GBS) |

| Paranodal focal demyelination (PFD) | Multifocal Motor Neuropathy (MMN) |

| Paranodal + focal demyelination (PIFD) | Multifocal Motor Neuropathy (MMN) |

Simple Models and Nonlinear Dynamical Analysis

Given the temporal dissociation between the manifestation of symptoms and the rates of demyelination and remyelination, homeostatic processes undoubtedly occur within axons, which include the redistribution of ion channels in demyelinated plaques.[106][107] But given the diversity of ion channels expressed by different axons and only patchy knowledge of how expression levels change, building detailed models to investigate those homeostatic processes is problematic. Especially under those conditions, highly simplified models can help identify fundamental principles, as exemplified by joint use of modified HH and Morris-Lecar models [57,58]. The results of those studies suggested a simple explanation for the breadth of symptoms encountered during demyelination by revealing that the ratio of Na+ to leak K+ conductance, g(Na)/g(L), acted as a four-way switch controlling excitability patterns that included failure of AP propagation, normal AP propagation, AD, and spontaneous spiking.

Further studies with this model suggested the potential for competition or cooperation between different regions of the same neuron.[59] Cooperativity between remote sites of ectopic spiking allows AD to be initiated and maintained at different locations within a single axon, thus providing a compelling explanation for the temporal and spatial discontinuities of pain and other symptoms presented by MS patients. Remarkably, in a recent study of demyelinated axons in a cuprizone mouse model, experimental evidence was seen for a redistribution of ion channels from the node of Ranvier, enhanced ectopic excitability along with antidromically propagated APs from the demyelinated plaque, as well as a compensatory shift in the excitability of membranes proximal to the soma.[108] All of these observations concur or are consistent with the computational model predictions of Coggan and colleagues and imply the success of the computational approach to guiding laboratory studies.

Furthermore, these simplified models enabled application of mathematical tools to examine the nonlinear mechanisms by which AD is initiated and terminated.[57][58][59] Bifurcation analysis revealed the underlying bistability of axon excitability under pathological conditions, as well as the factors controlling the transition from one attractor state to another. AD, for example, requires a slow inward current that allows for two stable attractor states, one corresponding to quiescence and the other to repetitive spiking (a limit cycle). Termination of AD was explained by the attractor associated with repetitive spiking being destroyed. This occurred when ultra-slow negative feedback in the form of intracellular Na+ accumulation caused the destruction of the limit-cycle attractor state [58]. Other studies using bifurcation analysis suggest that ion concentration changes can introduce slow dynamics that may be important for understanding pathological outcomes [94,109].[94][109]

Modeling at Small Scales

Studies mentioned above highlight the importance of ion concentration changes but each of them only considered those changes at a relatively course scale. By comparison, the study by Lorpreore et al.[110] tackled the daunting problem of modeling three-dimensional electro-diffusion of ion fluxes in micro and nano-domains surrounding ion channels at the node of Ranvier. In this unique model, the fluxes of ions are calculated by Poisson-Nernst-Planck equations with finite volume techniques. The fluxes and electric potentials were evaluated within voxels formed by a Delaunay-Voronoi mesh of the axon interior and exterior close to the membrane. Importantly, the algorithm was validated and results agreed with cable model predictions. Divergence from cable model predictions at smaller cluster sizes revealed the importance of each channel’s own electric field.

The above example highlights the point that models can simulate more than ion channels and membrane potential. Indeed, models can and must dig deeper into biophysical mechanisms like electro-diffusion and into signaling pathways that ultimately serve to regulate ion channel function and expression. A promising method called Biochemical Systems Theory (BST) may be useful in the future for pre-screening the effects of drugs at the systemic level. Broome and Coleman[111] demonstrated the power of this technique by modeling several biochemical pathways in neurons associated with cell death during MS including reactive oxygen and nitrogen species formation, Ca2+ dynamics, death complex formation, apoptotic factor release, and inflammatory responses together with three different states: normal, MS disease and treatment. At the atomic-level, a computational model of myelin basic protein (MBP) structure was carried-out because post-translational modifications of MBP may contribute to demyelination in MS.[112] It is important to understand its 3D structure to predict interaction sites with other molecules but a crystal structure for this protein might never be measured directly. This type of modeling may, therefore, represent an effective way to predict the structure by combining knowledge of amino acid sequence with information from similar proteins. The challenge for and the true power of modeling lies in connecting mechanisms that operate at vastly different scales, from molecular structure to the nervous system as a whole, and beyond, to address how the nervous system interacts with the immune system.

Models of Immune Factors. While there are numerous computational models of the immune system,[113] those related to MS typically model genetic interaction networks, either represented as sets of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) or Boolean networks. One systems biology model of a possible cellular mechanism of RRMS found breakdown in homeostasis of effector (Teff) and regulatory T (Treg) cells.[114][115] By changing parameters in the Teff-Treg feedback loop, under continual stochastic external stimulus from antigens, the model reproduced spontaneous and apparently stochastic immune relapses. The irreversible damage from each episode accumulates over time. Novel predictions include the suggestion that the timing of Treg immunotherapy in the immune response cycle is critical in determining whether intervention is beneficial or deleterious.

Models of Mitochondrial Dysfunction. As mentioned above, myelin enables more energy efficient AP conduction along the axon. The increased energy demands placed on the demyelinated axon represents yet another challenge to the afflicted neuron. Beyond the loss of saltatory conduction, there is mounting evidence of a critical role for astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in supplying energy to neurons and this process has also been the subject of computational modeling.[116]

There are many ways mitochondrial function can go awry and the compensatory pathways are equally complicated.[53][60][61] For example, mitochondrial dysfunction can be rooted in perturbed Ca2+ signaling within mitochondria, disrupted proton gradients or electron chain, reduction-oxidation imbalance as well as the consequences of reduced ATP availability, locally and globally. Multi-scale models of heart, for example, have been used to link altered mitochrondrial Ca2+ signaling to arrhythmia [60]. Using mitochondrial network modeling, this study demonstrated how even slightly too much reactive oxygen species can trigger a cell-wide collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential. This is an excellent example of how a computational model can link processes occurring at different levels, and it is precisely these linkages that must be established in the field of demyelination diseases.

Missing Links and the Need for Integration

Within the field of demyelinating diseases, modeling efforts have traditionally focused on axon models aimed at explaining various aspects of excitability. But as outlined above, those models have undergone tremendous evolution in complexity. In the process, models at different biological scales have begun to coalesce. For instance, models have now begun to address the regulation of ion concentrations and the consequences thereof for slow excitability changes, energy consumption, and toxicity. A computational approach will be necessary for integrating parallel and multifactorial etiologies associated with cognitive decline such as immune system signaling, energy metabolism, grey and white matter interactions, and genetic networks [117].[117] These continued efforts are starting to uncover the vast and interconnected feedback loops that operate across a broad range of spatial and temporal scales. That said, such efforts are still in their infancy and wide gaps remain in the modeling of demyelinating diseases. It is easier to describe what has been modeled than what has not. A truly integrated model involving multiple cell types that addresses all the hypothesized etiological factors remains unrealized. Among the unexplored or under-explored but potentially useful targets for modeling are grey matter pathology, myelin sheath aqueous layers, energy metabolism, and perhaps most importantly, multi-scale or integrated modeling. One should recognize that the necessary tools exist in other fields of study and can, therefore, be readily applied to the study of demyelination diseases.

Conclusions

The normal physiological function of the CNS or PNS relies on a highly regulated interplay of neurons, glia, vasculature and immune cells. This process encompasses and integrates numerous cellular and signaling components that produce a dynamical, computational whole. When any part goes awry, the entire system is forced to compensate. Even when compensation manages to rescue the most obvious consequences of demyelination, certain processes may not return to a completely normal state, which can lead to problems on longer time scales. The resulting symptoms are a confusing mixture of direct and compensatory changes that continuously evolve. The overall complexity has proven to be intractable to efficient experimental dissection. The application of computational modeling techniques represents an invaluable approach to help break the impasse and engender a new era of understanding and discovery.

Acknowledgments

Support provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and the Ontario Early Researcher Award (SAP). We thank Heiki Blum for assistance with figure preparation.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript. Figures were provided by Sven G. Meuth.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Article information

Int J Mol Sci. 2015 Sep; 16(9): 21215–21236. Published online 2015 Sep 7. doi: 10.3390/ijms160921215 PMCID: PMC4613250 PMID: 26370960 Jay S. Coggan,1,* Stefan Bittner,2 Klaus M. Stiefel,1 Sven G. Meuth,2 and Steven A. Prescott3,4 Christoph Kleinschnitz, Academic Editor 1NeuroLinx Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92039, USA; E-Mail: gro.xniloruen@sualk 2Department of Neurology, Institute of Physiology, Universitätsklinikum Münster, 48149 Münster, Germany; E-Mails: moc.kooltuo@renttib-nafets (S.B.); ed.retsneumku@htuem.nevs (S.G.M.) 3Neurosciences and Mental Health, the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON M5G 1X8, Canada; E-Mail: ac.sdikkcis@ttocserp.evets 4Department of Physiology and the Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5G 1X8, Canada

- Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: gro.xniloruen@yaj; Tel.: +1-858-243-6720.

Received 2015 May 26; Accepted 2015 Aug 25. Copyright © 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Articles from International Journal of Molecular Sciences are provided here courtesy of Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI)

Bibliography

- ↑ Virchow R. Uber das ausgebreitete Vorkommen einer dem Nervenmark analogen Substanz in den tierischen Geweben. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. 1854;6:562–572. doi: 10.1007/BF02116709. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stiefel K.M., Torben-Nielsen B., Coggan J.S. Proposed evolutionary changes in the role of myelin. Front. Neurosci. 2013;8 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00202.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bullock T.H., Moore J.K., Fields R.D. Evolution of myelin sheaths: Both lamprey and hagfish lack myelin. Neurosci. Lett. 1984;48:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90010-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Davis A.D., Weatherby T.M., Hartline D.K., Lenz P.H. Myelin-like sheaths in copepod axons. Nature. 1999;398:571–571. doi: 10.1038/19212. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hartline D.K., Colman D.R. Rapid conduction and the evolution of giant axons and myelinated fibers. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R29–R35. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.042. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Arancibia-Carcamo I.L., Attwell D. The node of ranvier in CNS pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:161–175. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1305-z.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Faisal A.A., White J.A., Laughlin S.B. Ion-channel noise places limits on the miniaturization of the brain’s wiring. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.056. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Babbs C.F., Riyi S. Subtle paranodal injury slows impulse conduction in a mathematical model of myelinated axons. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067767. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Trapp B.D., Nave K.A. Multiple sclerosis: An immune or neurodegenerative disorder? Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;31:247–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094313. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Compston A., Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ostermann P.O., Westerberg C.E. Paroxysmal attacks in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1975;98:189–202. doi: 10.1093/brain/98.2.189. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Twomey J.A., Espir M.L. Paroxysmal symptoms as the first manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1980;43:296–304. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.43.4.296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Seewann A., Vrenken H., van der Valk P., Blezer E.L., Knol D.L., Castelijns J.A., Polman C.H., Pouwels P.J., Barkhof F., Geurts J.J. Diffusely abnormal white matter in chronic multiple sclerosis: Imaging and histopathologic analysis. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:601–609. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.57. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ceccarelli A., Bakshi R., Neema M. MRI in multiple sclerosis: A review of the current literature. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2012;25:402–409. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328354f63f. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Moore J.W., Joyner R.W., Brill M.H., Waxman S.D., Najar-Joa M. Simulations of conduction in uniform myelinated fibers. Relative sensitivity to changes in nodal and internodal parameters. Biophys. J. 1978;21:147–160. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85515-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Waxman S.G., Kocsis J.D., Stys P.K. The Axon: Structure, Function and Pathophysiology. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Polman C.H., Reingold S.C., Banwell B., Clanet M., Cohen J.A., Filippi M., Fujihara K., Havrdova E., Hutchinson M., Kappos L., et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Stephanova D.I., Dimitrov B. Computational Neuroscience: Simulated Demyelinating Neuropathies and Neuronopathies. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Bostock H., Baker M., Reid G. Changes in excitability of human motor axons underlying post-ischaemic fasciculations: Evidence for two stable states. J. Physiol. 1991;441:537–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018766.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Mogyoros I., Kiernan M.C., Burke D., Bostock H. Strength-duration properties of sensory and motor axons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 1998;121:851–859. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.851. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kiernan M.C., Burke D., Andersen K.V., Bostock H. Multiple measures of axonal excitability: A new approach in clinical testing. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:399–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(200003)23:3<399::AID-MUS12>3.0.CO;2-G. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Cappelen-Smith C., Kuwabara S., Lin C.S., Mogyoros I., Burke D. Membrane properties in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Brain. 2001;124:2439–2447. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.12.2439. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Kuwabara S., Ogawara K., Sung J.Y., Mori M., Kanai K., Hattori T., Yuki N., MLin C.S., Burke D., Bostock H. Differences in membrane properties of axonal and demyelinating Guillain-Barré syndromes. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:180–187. doi: 10.1002/ana.10275. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Nodera H., Bostock H., Kuwabara S., Sakamoto T., Asanuma K., Jia-Ying S., Ogawara K., Hattori N., Hirayama M., Sobue G., et al. Nerve excitability properties in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain. 2004;127:203–211. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh020. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Sung M.H., Simon R. In silico simulation of inhibitor drug effects on nuclear factor-κB pathway dynamics. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:70–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.70. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Daskalova M. Differences in potentials and excitability properties in simulated cases of demyelinating neuropathies. Part III. Paranodal internodal demyelination. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2005;116:2334–2341. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.07.013. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Daskalova M.S. Differences between the channels, currents and mechanisms of conduction slowing/block and accommodative processes in simulated cases of focal demyelinating neuropathies. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008;37:829–842. doi: 10.1007/s00249-008-0284-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Alexandrov A.S. Simulating mild systematic and focal demyelinating neuropathies: Membrane property abnormalities. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2006;5:595–623. doi: 10.1142/S0219635206001331. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Daskalova M., Alexandrov A.S. Channels, currents and mechanisms of accommodative processes in simulated cases of systematic demyelinating neuropathies. Brain Res. 2007;1171:138–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.029. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Stephanova D.I., Krustev S.M., Negrev N., Daskalova M. The myelin sheath aqueous layers improve the membrane properties of simulated chronic demyelinating neuropathies. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2011;10:105–120. doi: 10.1142/S0219635211002646. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Alexandrov A.S., Kossev A., Christova L. Simulating focal demyelinating neuropathies: Membrane property abnormalities. Biol. Cybern. 2007;96:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s00422-006-0113-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bø L., Geurts J.J., Mörk S.J., van der Valk P. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2006;183:48–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00615.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Geurts J.J., Barkhof F. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:841–851. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70191-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Zivadinov R., Pirko I. Advances in understanding gray matter pathology in multiple sclerosis: Are we ready to redefine disease pathogenesis? BMC Neurol. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Popescu B.F., Lucchinetti C.F. Pathology of demyelinating diseases. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2012;7:185–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132443.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Kurtzke J.F., Beebe G.W., Nagler B., Nefzger M.D., Auth T.L., Kurland L.T. Studies on the natural history of multiple sclerosis: V. Long-term survival in young men. Arch. Neurol. 1970;22:215–225. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480210025003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Rao S.M., Leo G.J., Bernardin L., Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991;41:685–691. doi: 10.1212/WNL.41.5.685. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Meuth S.G., Bittner S., Ulzheimer J.C., Kleinschnitz C., Kieseier B.C., Wiendl H. Therapeutic approaches to multiple sclerosis: An update on failed, interrupted, or inconclusive trials of neuroprotective and alternative treatment strategies. BioDrugs. 2010;24:317–330. doi: 10.2165/11537190-000000000-00000. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Goldenberg M.M. Multiple sclerosis review. Pharm. Ther. 2012;37:137–139.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Göbel K., Wedell J.H., Herrmann A.M., Wachsmuth L., Pankratz S., Bittner S., Budde T., Kleinschnitz C., Faber C., Wiendl H., et al. 4-Aminopyridine ameliorates mobility but not disease course in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 2013;248:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.016.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Krishnan A.V., Kiernan M.C. Sustained-release fampridine and the role of ion channel dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2013;19:385–391. doi: 10.1177/1352458512463769. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bowe C.M., Kocsis J.D., Targ E.F., Waxman S.G. Physiological effects of 4-aminopyridine on demyelinated mammalian motor and sensory fibers. Ann. Neurol. 1987;22:264–268. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220212. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Sakurai M., Kanazawa I. Positive symptoms in multiple sclerosis: Their treatment with sodium channel blockers, lidocaine and mexiletine. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999;162:162–168. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00322-0. [PubMed]

- ↑ Mattson M.P., Guthrie P.B., Kater S.B. A role for Na+-dependent Ca2+extrusion in protection against neuronal excitotoxicity. FASEB J. 1989;3:2519–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Moll N.M., Rietsch A.M., Thomas S., Ransohoff A.J., Lee J.C., Fox R., Chang A., Ransohoff R.M., Fisher E. Multiple sclerosis normal-appearing white matter: Pathology-imagig correlations. Ann. Neurol. 2011;70:764–773. doi: 10.1002/ana.22521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Lucchinetti C., Brück W., Parisi J., Scheithauer B., Rodriguez M., Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: Implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann. Neurol. 2000;47:707–717. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707::AID-ANA3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Kassmann C.M., Nave K.A. Oligodendroglial impact on axonal function and survival— A hypothesis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008;21:235–241. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328300c71f. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Scolding N., Franklin R. Axon loss in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:340–341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60463-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Mi S., Miller R.H., Lee X., Scott M.L., Shulag-Morskaya S., Shao Z., Chang J., Thill G., Levesque M., Zhang M., et al. LINGO-1 negatively regulates myelination by oligodendrocytes. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:745–751. doi: 10.1038/nn1460. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bittner S., Ruck T., Schuhmann M.K., Herrmann A.M., Maati H.M., Bobak N., Göbel K., Langhauser F., Stegner D., Ehling P., et al. 2013 Endothelial TWIK-related potassium channel-1 (TREK1) regulates immune-cell trafficking into the CNS. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1161–1165. doi: 10.1038/nm.3303. [PubMed]

- ↑ Viglietta V., Baecher-Allan C., Weiner H.L., Hafler D.A. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:971–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Zajicek J.P., Wing M., Scolding N.J., Compston D.A. Interactions between oligodendrocytes and microglia. A major role for complement and tumour necrosis factor in oligodendrocyte adherence and killing. Brain. 1992;115:1611–1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Nikić I., Merkler D., Sorbara C., Brinkoetter M., Kreutzfeldt M., Bareyre F.M., Brück W., Bishop D., Misgeld T., Kerschensteiner M. A reversible form of axon damage in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2011;17:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nm.2324. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Barnett M.H., Prineas J.W. Relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis: Pathology of the newly forming lesion. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:458–468. doi: 10.1002/ana.20016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Van der Laan L.J., Ruuls S.R., Weber K.S., Lodder I.J., Döpp E.A., Dijkstra C.D. Macrophage phagocytosis of myelin in vitro determined by flow cytometry: Phagocytosis is mediated by CR3 and induces production of tumor necrosis factor-α and nitric oxide. J. Neuroimmunol. 1996;70:145–152. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(96)00110-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Wang G., Thompson S.M. Maladaptive homeostatic plasticity in a rodent model of central pain syndrome: Thalamic hyperexcitability after spinothalamic tract lesions. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:11959–11969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3296-08.2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Coggan J.S., Prescott S.A., Bartol T.M., Sejnowski T.J. Imbalance of ionic conductances contributes to diverse symptoms of demyelination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20602–20609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013798107.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Coggan J.S., Ocker G.K., Sejnowski T.J., Prescott S.A. Explaining pathological changes in axonal excitability through dynamical analysis of conductance-based models. J. Neural Eng. 2011;8 doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/6/065002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Coggan J.S., Prescott S.A., Sejnowski T.J. Cooperativity between remote sites of ectopic spiking allows afterdischarge to be initiated and maintained at different locations. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2015;39:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10827-015-0562-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Aon M.A., Cortassa S., Akar F.G., Brown D.A., Zhou L., O’Rourke B. From mitochondrial dynamics to arrhythmias. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;41:1940–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.02.016. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Su K., Bourdette D., Forte M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Front. Physiol. 2013;4doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Soltesz I., Staley K. Computational Neuroscience in Epilepsy. 1st ed. Elsevier; London, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hodgkin A.L., Huxley A.F. The components of membrane conductance in the giant axon of Loligo. J. Physiol. 1952;116:473–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hodgkin A.L., Huxley A.F. Currents carried by sodium and potassium ions through the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J. Physiol. 1952;116:449–472. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004717. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- ↑ Fitzhugh R. Computation of impulse initiation and saltatory conduction in a myelinated nerve fiber. Biophys. J. 1962;2:11–21. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(62)86837-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Goldman L., Albus J.S. Computation of impulse conduction in myelinated fibers; theoretical basis of the velocity-diameter relation. Biophys. J. 1968;8:596–607. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(68)86510-5. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Frankenhaeuser B., Huxley A.F. The action potential in the myelinated nerve fiber of Xenopus laevis as computed on the basis of voltage clamp data. J. Physiol. 1964;171:302–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007378.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Smith R.S., Koles Z.J. Myelinated nerve fibers: Computed effect of myelin thickness on conduction velocity. Am. J. Physiol. 1970;219:1256–1258.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hutchinson N.A., Koles Z.J., Smith R.S. Conduction velocity in myelinated nerve fibres of Xenopus laevis. J. Physiol. 1970;208:279–289. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Koles Z.J., Rasminsky M. A computer simulation of conduction in demyelinated nerve fibres. J. Physiol. 1972;227:351–364. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp010036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hardy W.L. Propagation speed in myelinated nerve. II. Theoretical dependence on external Na and on temperature. Biophys. J. 1973;13:1071–1089. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(73)86046-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Schauf C.L., Davis F.A. Impulse conduction in multiple sclerosis: A theoretical basis for modification by temperature and pharmacological agents. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1974;37:152–161. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.37.2.152.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Brill M.H., Waxman S.G., Moore J.W., Joyner R.W. Conduction velocity and spike configuration in myelinated fibres: Computed dependence on internode distance. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1977;40:769–774. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.40.8.769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Waxman S.G., Brill M.H. Conduction through demyelinated plaques in multiple sclerosis: Computer simulations of facilitation by short internodes. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1978;41:408–416. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.41.5.408.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Wood S.L., Waxman S.G., Kocsis J.D. Conduction of trans of impulses in uniform myelinated fibers: Computed dependence on stimulus frequency. Neuroscience. 1982;7:423–430. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90276-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Goldfinger M.D. Computation of high safety factor impulse propagation at axonal branch points. Neuroreport. 2000;11:449–456. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Blight A.R. Computer simulation of action potentials and afterpotentials in mammalian myelinated axons: The case for a lower resistance myelin sheath. Neuroscience. 1985;15:13–31. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90119-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Halter J.A., Clark J.W., Jr. A distributed-parameter model of the myelinated nerve fiber. J. Theor. Biol. 1991;148:345–382. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80242-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Schwarz J.R., Eikhof G. Na currents and action potentials in rat myelinated nerve fibres at 20 and 37 °C. Pflugers Arch. 1987;409:569–577. doi: 10.1007/BF00584655. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Stephanova D.I. Myelin as longitudinal conductor: A multi-layered model of the myelinated human motor nerve fibre. Biol. Cybern. 2001;84:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s004220000213. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 McIntyre C.C., Richardson A.G., Grill W.M. Modeling the excitability of mammalian nerve fibers: Influence of afterpotentials on the recovery cycle. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:995–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Einziger P.D., Livshitz L.M., Mizrahi J. Generalized cable equation model for myelinated nerve fiber. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2005;52:1632–1642. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.856031. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Volman V., Ng L. Primary paranode demyelination modulates slowly developing axonal depolarization in a model of axonal injury. J. Neural Comput. 2014;37:439–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Bostock H. A Distributed-parameter model of the myelinated human motor nerve fibre: Temporal and spatial distributions of action potentials and ionic currents. Biol. Cybern. 1995;73:275–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00201429. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Chiu S.Y., Ritchie J.M. On the physiological role of internodal potassium channels and the security of conduction in myelinated nerve fibres. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1984;220:415–422. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0010.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Brismar T., Schwarz J.R. Potassium permeability in rat myelinated nerve fibres. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1985;124:141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1985.tb07645.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Chiu S.Y., Schwarz W. Sodium and potassium currents in acutely demyelinated internodes of rabbit sciatic nerves. J. Physiol. 1987;391:631–649. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016760. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Baker M., Bostock H., Grafe P., Martius P. Function and distribution of three types of rectifying channel in rat spinal root myelinated axons. J. Physiol. 1987;383:45–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar

- ↑ Röper J., Schwarz J.R. Heterogeneous distribution of fast and slow potassium channels in myelinated rat nerve fibres. J. Physiol. 1989;416:93–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bittner S., Meuth S.G. Targeting ion channels for the treatment of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2013;6:322–336. doi: 10.1177/1756285613487782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Waxman S.G., Ritchie J.M. Molecular dissection of the myelinated axon. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33:121–136. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330202. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Bittner S., Budde T., Wiendl H., Meuth S.G. From the background to the spotlight: TASK channels in pathological conditions. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:999–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00407.x. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ehling P., Bittner S., Budde T., Wiendl H., Meuth S.G. Ion channels in autoimmune neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3836–3842. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.065. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Hübel N., Dahlem M.A. Dynamics from seconds to hours in Hodgkin-Huxley model with time-dependent ion concentrations and buffer reservoirs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003941.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ganapathy L., Clark J.W. Extracellular currents and potentials of the active myelinated nerve fibre. Biophys. J. 1987;52:749–761. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83269-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Prescott S.A. Pathological changes in peripheral nerve excitability. In: Jaeger D., Jung R., editors. Encyclopedia of Computational Neurosci. 1st ed. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Barrett E.F., Barrett J.N. Intracellular recording from vertebrate myelinated axons: Mechanism of the depolarizing afterpotential. J. Physiol. 1982;323:117–144. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014064. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Blight A.R., Someya S. Depolarizing afterpotentials in myelinated axons of mammalian spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1985;15:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90118-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Richardson A.G., McIntyre C.C., Grill W.M. Modelling the effects of electric fields on nerve fibres: Influence of the myelin sheath. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2000;38:438–446. doi: 10.1007/BF02345014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Zlochiver S. Persistent reflection underlies ectopic activity in multiple sclerosis: A numerical study. Biol. Cybern. 2010;102:181–196. doi: 10.1007/s00422-009-0361-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ratté S., Zhu Y., Lee K.Y., Prescott S.A. Criticality and degeneracy in injury-induced changes in primary afferent excitability and the implications for neuropathic pain. Elife. 2014;3:e02370. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02370.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Zhu Y., Feng B., Schwartz E.S., Gebhart G.F., Prescott S.A. Novel method to assess axonal excitability using channelrhodopsin-based photoactivation. J. Neurophysiol. 2015;113:2242–2249. doi: 10.1152/jn.00982.2014.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Tagoe T., Barker M., Jones A., Allcock N., Hamann M. Auditory nerve perinodal dysmyelination in noise-induced hearing loss. J. Neurosci. 2014;12:2684–2688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3977-13.2014.

- ↑ Brown A.M., Hamann M. Computational modeling of the effects of auditory nerve dysmyelination. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00073. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stephanova D.I., Daskalova M. Electrotonic potentials in simulated chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy at 20 °C–42 °C. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2015;27:1–18. doi: 10.1142/S0219635215500119. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Rasminsky M. Hyperexcitability of pathologically myelinated axons and positive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Adv. Neurol. 1981;31:289–297.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ulrich J., Groebke-Lorenz W. The optic nerve in multiple sclerosis: A morphological study with retrospective clinicopathological correlation. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 1983;3:149–159. doi: 10.3109/01658108309009732.[CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Hamada M.S., Kole M.H. Myelin loss and axonal ion channel adaptations associated with gray matter neuronal hyperexcitability. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:7272–7786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Yu N., Morris C.E., Joós B., Longtin A. Spontaneous excitation patterns computed for axons with injury-like impairments of sodium channels and Na/K pumps. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Lopreore C.L., Bartol T.M., Coggan J.S., Keller D.X., Sosinsky G.E., Ellisman M.H., Sejnowski T.J. Computational modeling of three-dimensional electrodiffusion in biological systems: Application to the node of Ranvier. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2624–2635. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132167.

- ↑ Broome T.M., Cole.man R.A. A mathematical model of cell death in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2011;201:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.08.008. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Ridsdale R.A., Beniac D.R., Tompkins T.A., Moscarello M.A., Harauz G. Three-dimensional structure of myelin basic protein. II. Molecular modeling and considerations of predicted structures in multiple sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4269–4275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4269. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Pigozzo A.B., Macedo G.C., Santos R.W., Lobosco M. On the computational modeling of the innate immune system. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S6-S7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Doerck S., Göbel K., Weise G., Schneider-Hohendorf T., Reinhardt M., Hauff P., Schwab N., Linker R., Mäurer M., Meuth S.G., et al. Temporal pattern of ICAM-I mediated regulatory T cell recruitment to sites of inflammation in adoptive transfer model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ De Mendizábal N.V., Carneiro J., Solé R.V., Goñi J., Bragard J., Martinez-Forero I., Martinez-Pasamar S., Sepulcre J., Torrealdea J., Bagnato F., et al. Modeling the effector-regulatory T cell cross-regulation reveals the intrinsic character of relapses in Multiple Sclerosis. BMC Syst. Biol. 2011;5doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Jolivet R., Coggan J.S., Allaman I., Magistretti P.J. Multi-timescale modeling of activity-dependent metabolic coupling in the neuron-glia-vasculature ensemble. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- ↑ Zeis T., Allaman I., Gentner M., Schroder K., Tschopp J., Magistretti P.J., Schaeren-Wiemers N. Metabolic gene expression changes in astrocytes in Multiple Sclerosis cerebral cortex are indicative of immune-mediated signaling. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015;48:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.013.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]