Store:EEMIit05

In practice

These two equations are how we create our quasi-quantum mechanical analogues. The second equation is an extension of Ehrenfest’s theorem, relating the average momenta of a particle to the time derivative of its average position. Where we have assumed a Hamiltonian with only a spatially dependent potential. Note that as the positions are fixed in space (positions of the electrodes) only the probability changes in time. Throughout this paper the mass m has been taking to be unity for both the and momenta. Each of the 92 electrodes were projected onto the horizontal plane, thus the th electrode was described by one unique point.

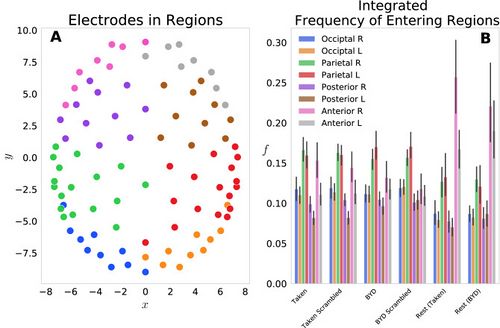

We first examined this model by grouping the 92 electrodes into eight regions on the scalp: Anterior L/R, Posterior L/R, Parietal L/R, Occipital L/R and the probabilities of each electrode in the region were summed to give a region-level probability. Figure 1A shows the locations of each electrode, with different colours representing each of the eight groups. Figure 1B displays the frequency of entering each region, grouped by the four task conditions and two resting conditions. This reflects the normalized count of regional probabilities integrated in time. We found that each anterior region was entered more frequently while at rest than when subjects were engaged in either movie. Specifically, the anterior left and right regions had significant within stimulus change, with (Tukey adjusted) for the Taken Rest—Taken, Taken Rest—Taken Scrambled, BYD Rest—BYD and BYD Rest—BYD Scrambled. This is in line with Axelrod and colleagues’ findings which showed activation in the frontal region was associated with mind wandering[1][2]. We found frequency suppression in posterior regions, and an increase in anterior frequency in rest compared to the stimulated conditions, consistent with fMRI studies showing increased activation in the posterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex during rest [3][2][4][5][6][7]. Thus, suggesting our model captures the frontal tendency associated with the brain activity while at rest.

Phase space

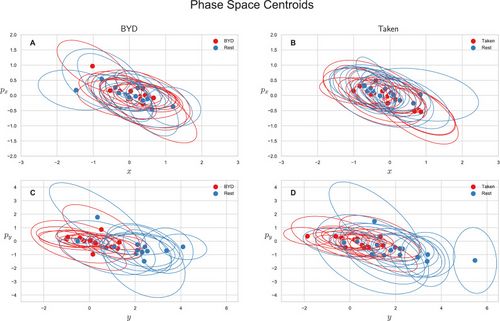

We also explored the average-valued phase space of this system. The phase space for each subject was plotted as the average position and momentum along the direction or as the average position and momentum along the direction . Figure 2 shows the centroids of the phase space scatter plots for each subject with an ellipse representing the one standard deviation confidence interval. Note that values are only reported for the intact stimuli as an analysis of variance shows the scrambled and intact movies are indistinguishable in phase space (P, Tukey adjusted). Figure 2A and B show the projection of the phase space centroid onto the plane spanned by and for “Bang! You’re Dead” and “Taken” respectively, and Fig. 2C and D () plane. The average position along the axis for the intact stimulus (“BYD” and “Taken”) and their scrambled forms are significantly different from the pre-stimulus rest counterparts with (Tukey adjusted) whereas the task-positive and resting centroids are indistinguishable in the plane (, Tukey adjusted). The averages of the group are reported in Table Table11 along with their standard deviations. These values are the averaged value of the centroids (average of the within stimuli centre points in Fig. 2) for the respective position/momenta within each stimulus level. As also seen in Fig. 2C and D, there is a striking difference of one order of magnitude for between the resting and task conditions, yet no marked differences in , , or .

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:8 - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:3 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:2 - ↑ Wang RWY, Chang WL, Chuang SW, Liu IN. Posterior cingulate cortex can be a regulatory modulator of the default mode network in task-negative state. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–12. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Uddin LQ, Kelly AMC, Biswal BB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Functional connectivity of default mode network components: Correlation, anticorrelation, and causality. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;30:625–637. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20531. [PMC free article][PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Stawarczyk D, Majerus S, Maquet P, D’Argembeau A. Neural correlates of ongoing conscious experience: Both task-unrelatedness and stimulus-independence are related to default network activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016997.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Greicius, M. D., Krasnow, B., Reiss, A. L., Menon, V. & Raichle, M. E. Functional Connectivity in the Resting Brain: A Network Analysis of the Default Mode Hypothesis. www.pnas.org. [PMC free article] [PubMed]