The logic of classical language - fr

| Other languages: |

La logique classique sera abordée dans ce chapitre. Dans une première partie, le formalisme mathématique et les règles qui le composent seront illustrés. Dans la deuxième partie, un exemple clinique sera donné pour évaluer son efficacité dans la détermination d'un diagnostic.

En conclusion, il est évident qu'une logique classique du langage, qui a une approche extrêmement dichotomique (soit quelque chose est blanc, soit c'est noir), ne peut pas décrire les nombreuses nuances que présentent les situations cliniques réelles.

Comme nous le verrons bientôt, cet article montrera que la logique classique manque de la précision nécessaire, nous forçant à l'enrichir avec d'autres types de langages logiques.

Introduction

Nous nous sommes séparés dans le chapitre précédent sur la « logique du langage médical » dans une tentative de déplacer l'attention du symptôme clinique ou du signe vers le langage machine crypté pour lequel les arguments de Donald E Stanley, Daniel G Campos et Pat Croskerry sont les bienvenus mais connecté au temps comme support d'information (anticipation du symptôme) et au message comme langage machine et non comme langage non verbal).[1][2]

Cela n'exclut évidemment pas la validité de l'histoire clinique bâtie sur un langage verbal pseudo-formel désormais bien ancré dans la réalité clinique et qui a déjà prouvé son autorité diagnostique. La tentative de déplacer l'attention vers un langage machine et vers le système n'offre rien d'autre qu'une opportunité pour la validation de la science médicale diagnostique.

Nous sommes certainement conscients que notre Linux Sapiens est toujours perplexe quant à ce qui a été anticipé et continue de se demander

«... but... la logique du langage classique pourrait-elle nous aider à résoudre le dilemme de la pauvre Mary Poppins ?»

(a little patience, please) |

Nous ne pouvons apporter une réponse conventionnelle car la science ne progresse pas avec des affirmations qui ne sont pas justifiées par des questions et des réflexions scientifiquement validées ; et c'est d'ailleurs la raison pour laquelle nous tenterons de donner la parole à quelques réflexions, perplexités et doutes exprimés sur quelques sujets de fond mis en discussion dans certains articles scientifiques.

L'un de ces sujets fondamentaux est la «biologie craniofaciale».

Commençons par une étude bien connue de Townsend et Brook[3]:dans ce travail, les auteurs remettent en question le statu quo de la recherche fondamentale et appliquée en «biologie craniofaciale» pour en extraire des considérations et des implications cliniques. L'un des sujets qu'ils ont abordés était "l'approche interdisciplinaire", dans laquelle Geoffrey Sperber et son fils Steven ont vu la force des progrès exponentiels de la "biologie craniofaciale" dans les innovations technologiques telles que le séquençage de gènes, la tomodensitométrie, l'imagerie IRM, le laser à balayage, l'analyse d'images. , échographie et spectroscopie[4].

Un autre sujet de grand intérêt pour la mise en œuvre de la «biologie craniofaciale» est la prise de conscience que les systèmes biologiques sont des «systèmes complexes».'[5]et que «l'épigénétique» joue un rôle clé dans la biologie moléculaire craniofaciale. Des chercheurs d'Adélaïde et de Sydney livrent une revue critique dans le domaine de l'épigénétique visant, en fait, les disciplines dentaires et craniofaciales.[6] La phénomique, en particulier, discutée par ces auteurs (voir Phénomique)) est un domaine de recherche général qui implique la mesure des changements dans les dents et les structures orofaciales associées résultant des interactions entre les facteurs génétiques, épigénétiques et environnementaux au cours du développement.t.[7] Dans ce même contexte, le travail d'Irma Thesleff d'Helsinki, en Finlande, mérite d'être souligné. Elle explique dans son travail qu'il existe une série de centres de signalisation transitoire dans l'épithélium dentaire qui jouent un rôle important dans le programme de développement des dents..[8] En outre, il existe d'autres travaux, par Peterkova R, Hovor akova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, fournissant un examen fascinant des processus qui se produisent au cours du développement dentaire.;[9][10][11] dans un souci d'exhaustivité, n'oublions pas les travaux de Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S et Bartold PM., qui passent en revue une documentation complète sur les cellules souches, l'ingénierie tissulaire et la régénération parodontale.[12]

Dans cette revue, les arguments ne pouvaient manquer sur les influences génétiques, épigénétiques et environnementales au cours de la morphogenèse qui conduisent à des variations du nombre, de la taille et de la forme de la dent.[13][14]et l'influence de la pression de la langue sur la croissance et la fonction craniofaciale.[15][16]Le travail extraordinaire de Townsend et Brook mérite également une mention[3], et le contenu intrinsèque de ce qui y a été rapporté correspond tout aussi bien à un autre auteur louable : HC Slavkin.[17] Slavkin affirme que :

- "L'avenir regorge d'opportunités significatives pour améliorer les résultats cliniques des malformations craniofaciales congénitales et acquises. Les cliniciens jouent un rôle clé car la pensée critique et le public clinique améliorent considérablement la précision du diagnostic et donc les résultats de santé cliniques."

«... Je comprends les progrès de la science décrits par les auteurs mais je ne comprends pas le changement de bient»

(Je vais vous donner un exemple pratique) |

Dans le chapitre "Introduction" nous avons posé certaines questions au sujet de la malocclusion mais dans ce cadre nous simulons la logique du langage médical du dentiste face au cas clinique présenté dans le "chapitre Introduction" avec ses conclusions diagnostiques et thérapeutiques.

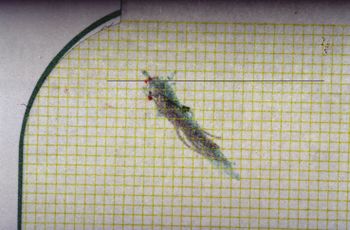

Le patient a une occlusion croisée unilatérale postérieure et une béance antérieure.[18] L'occlusion croisée est un autre élément perturbateur de l'occlusion normale[19] pour lequel il est obligatoirement traité en même temps que la béance.[20][21] Ce type de raisonnement signifie que le modèle (système masticatoire) est « normalisé à l'occlusion » ; et lu à l'envers, cela signifie que le décalage occlusal est la cause d'une malocclusion, donc d'une maladie de l'appareil masticatoire, et donc une intervention pour restaurer la fonction masticatoire physiologique est justifiable. (Figure 1a).

Cet exemple est le langage logique classique, comme nous allons l'expliquer en détail, mais maintenant un doute surgit :

- A l'époque où les axiomes orthodontiques et orthognathiques construisaient des protocoles confirmés par la Communauté Scientifique Internationale, avaient-ils connaissance des informations dont nous avons parlé dans l'introduction de ce chapitre ?

(bien sûr, mais la suite logique a déjà été anticipée)

Si le même cas était interprété avec un état d'esprit qui suivait une « logique du langage du système » (cela sera discuté dans le chapitre approprié), les conclusions seraient surprenantes.

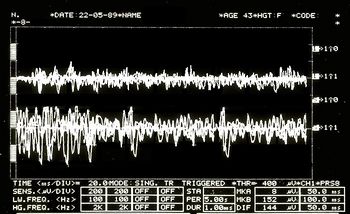

Si l'on observe les réponses électrophysiologiques effectuées sur le patient avec malocclusion dans les figures 1b, 1c et 1d (avec l'explication faite directement en légende pour simplifier la discussion), on remarquera que ces données peuvent faire penser à tout sauf à une « malocclusion ». ' et, par conséquent, les axiomes de type 'cause/effet' orthodontiques et orthognathiques laissent un vide conceptuel.«Permettez-moi de mieux comprendre ce que la logique du langage classique a à voir avec cela»

(Nous le ferons suite au cas clinique de notre Mary Poppins) |

Mathematical formalism

In this chapter, we will reconsider the clinical case of the unfortunate Mary Poppins suffering from Orofacial Pain for more than 10 years to which her dentist diagnosed a 'Temporomandibular Disorders' (TMDs) or rather Orofacial Pain from TMDs. To better understand why the exact diagnostic formulation remains complex with a Logic of Classical Language, we should understand the concept on which the philosophy of classical language is based with a brief introduction to the topic.

Propositions

Classical logic is based on propositions. It is often said that a proposition is a sentence that asks whether the proposition is true or false. Indeed, a proposition in mathematics is usually either true or false, but this is obviously a little too vague to be a definition. It can be taken, at best, as a warning: if a sentence, expressed in common language, makes no sense to ask whether it is true or false, it will not be a proposition but something else.

It can be argued whether or not common language sentences are propositions as in many cases it is not often evident if a certain statement is true or false.

Fortunately, mathematical propositions, if well expressed, do not show such ambiguities’.

Simpler propositions can be combined with each other to form new, more complex propositions. This occurs with the help of operators called logical operators and quantifying connectives which can be reduced to the following[22]:

- Conjunction, which is indicated by the symbol (and):

- Disjunction, which is indicated by the symbol (or):

- Negation, which is indicated by the symbol (not):

- Implication, which is indicated by the symbol (if ... then):

- Consequence, which is indicated by the symbol (is a partition of..):

- Universal quantifier, which is indicated by the symbol (for all):

- Demonstration, which is indicated by the symbol (such that): and

- Membership, which is indicated by the symbol (is an element of) or by the symbol (is not an element of):

Demonstration by absurdity

Furthermore, in classical logic there is a principle called the excluded third which declares that a sentence that cannot be false must be taken as true since there is no third possibility.

Suppose we need to prove that the proposition is true. The procedure consists in showing that the assumption that is false leads to a logical contradiction. Thus the proposition cannot be false, and therefore, according to the law of the excluded third, it must be true. This method of demonstration is called demonstration by absurdity[23]

Predicates

What we have briefly described so far is the logic of propositions. A proposition asserts something about specific mathematical objects such as: '2 is greater than 1, so 1 is less than 2' or 'a square has no 5 sides then a square is not a pentagon'. Many times, however, the mathematical statements concern not the single object, but generic objects of a set such as: ' are taller than 2 meters' where denotes a generic group (for example all volleyball players). In this case we speak of predicates.

Intuitively, a predicate is a sentence concerning a group of elements (which in our medical case will be the patients) and which states something about them.«Then poor Mary Poppins is a TMD patient or she is not!»

(let's see what Classical Language Logic tells us) |

2nd Clinical Approach

(Hover over the images)

Dental propositions

While seeking to use the mathematical formalism to translate the conclusions reached by the dentist with classical logic language, we consider the following predicates:

- x Normal patients (normal stands for patients commonly present in the specialist setting)

- Bone remodelling with osteophyte from stratigraphic examination and condylar CT; and

- Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) resulting in Orofacial Pain (OP)

- Specific patient: Mary Poppins

Any normal patient who is positive on the radiographic examination of the TMJ [Figure 2 and 3] is affected by TMDs ; from this it follows that being Mary Poppins positive (and also being a "Normal" patient) on the TMJ x-ray then Mary Poppins is also affected by TMDs The language of predicates is expressed in the following way:

.

At this point, it must also be considered that predicate logic is not used only to prove that a particular set of premises imply a particular evidence . It is also used to prove that a particular assertion is not true, or that a particular piece of knowledge is logically compatible/incompatible with a particular evidence.

In order to prove that this proposition is true we must use the above mentioneddemonstration by absurdity. If its denial creates a contradiction, surely the dentist's proposition will be true:

.

"" states that it is not true that those who test positive on TMJ CT have TMDs, so Mary Poppins (TMJ CT positive normal patient) does not have TMDs.

The dentist believes that Mary Poppins' claim (that she does not have TMD under these premises) is a contradiction so the main claim is true.

Neurophysiological proposition

Let us imagine that the neurologist disagrees with the conclusion and asserts that Mary Poppins is not affected by TMDs or that at least it is not the main cause of Orofacial Pain, but that, rather, she is affected by a neuromotor Orofacial Pain (nOP), therefore that she does not belong to the group of 'normal patients' but is to be considered a 'non-specific patient' (uncommon in the specialist context).

Obviously, this dialectic would last indefinitely because both would defend their scientific-clinical context; but let us see what happens in the logic of predicates.

The neurologist's statement would be like:

.

"" means that every patient who is TMJ CT positive has TMDs but even though Mary Poppins is TMJ CT positive, she does not have TMDs.

In order to prove that this proposition is true, we must use once again the above mentioned demonstration by absurdity. If its denial creates a contradiction, surely the neurologist's proposition will be true:

.

Following the logical rules of predicates, there is no reason to say that denial (4) is contradictory or meaningless, therefore the neurologist (unlike the dentist) would not seem to have the logical tools to confirm his conclusion.«then the dentist triumphs!»

(don't take it for granted) |

Compatibility and incompatibility of the statements

The complication lies in the fact that the dentist will present a series of statements as clinical reports such as the stratigraphy and CT of the TMJ, that indicate an anatomical flattening of the joint, axiography of the condylar traces with a reduction in kinematic convexity and a tracing EMG interference pattern in which an asymmetrical pattern on the masseters is highlighted. These assertions can easily be considered a contributing cause of the damage to the Temporomandibular Joint and, therefore, responsible for the 'Orofacial pain'.

Documents, reports and clinical evidence can be used to make the neurologist's assertion incompatible and the dentist's diagnostic conclusion compatible. To do this we must present some logical rules that describe the compatibility or incompatibility of the logic of classical language:

- A set of sentences , and a number of other phrases or statements are logically compatible if, and only if, the union between them is coherent.

- A set of sentences , and a number of other phrases or statements are logically incompatible if, and only if, the union between them is incoherent.

Let us try to follow this reasoning with practical examples:

The dentist colleague exposes the following sentence:

: Following the personalized techniques suggested by Xin Liang et al.[28] who focuses on the quantitative microstructural analysis of the fraction of the bone value, the trabecular number, the trabecular thickness and the trabecular separation on each slice of the CT scan of a TMJ, it appears that Mary Poppins is affected by Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) and the consequence causes Orofacial Pain.

At this point, however, the thesis must be confirmed with further clinical and laboratory tests, and in fact the colleague produces a series of assertions that should pass the compatibility filter as described above, namely:

Bone remodelling: The flattening of the axiographic traces highlighted in figure 5 indicates the joint remodelling of the right TMJ of Mary Poppins, such a report can be correlated to a series of researches and articles that confirm how malocclusion can be associated with morphological changes in the temporomandibular joints, particularly when combined with the age as the presence of a chronic malocclusion can worsen the picture of bone remodelling.[29] These scientific references determine the compatibility of the assertion.

Sensitivity and specificity of the axiographic measurement: A study was conducted to verify the sensitivity and specificity of the data collected from a group of patients affected by temporomandibular joint disorders with an ARCUSdigma axiographic system[30]; it confirmed a sensitivity of the 84.21% and a 92.86% sensitivity for the right and left TMJs respectively, and a specificity of 93.75% and 95.65%.[31] These scientific references determine compatibility of the assertion in the dental context precisely because of the consistency of related studies.[32]

Alteration of condylar paths: Urbano Santana-Mora and coll.[33] evaluated 24 adult patients suffering from severe chronic unilateral pain diagnosed as Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs). The following functional and dynamic factors were evaluated:

masticatory function;

remodelling of the TMJ or condylar pathway (CP); and lateral movement of the jaw or lateral guide (LG).

The CPs were assessed using conventional axiography and LG was assessed by using kinesiograph tracing[34]; Seventeen (71%) of the 24 (100%) patients consistently showed a side of habitual chewing side. The mean and standard deviation of the CP angles was 47.90 9.24) degrees. The average of LG angles was 42.9511.78 degrees.

Data collection emerged from the conception of a new TMD paradigm in which the affected side could be the usual chewing side, the side where the mandibular lateral kinematic angle was flatter. This parameter may also be compatible with the dental claim.

EMG Intereference pattern: M.O. Mazzetto and coll.[35] showed that the electromyographic activity of the anterior temporal muscles and the masseter was positively correlated with the "Craniomandibular index", indiced (CMI) with a and suggesting that the use of CMI to quantify the severity of TMDs and EMG to assess the masticatory muscle function, may be an important diagnostic and therapeutic elements. These scientific references determine compatibility of the assertion.

?

Obviously, the dentist colleague could endlessly keep on casting his statements, indefinitely.

Well, all of these statements seem coherent with the sentence initially described, whereby the dentist colleague feels justified in saying that the set of sentences , and a number of other assertions or clinical data are logically compatible as the union between them is coherent.«Following the logic of classical language, the dentist is right!»

(It would seem so! But, be careful, only in his own dental context!) |

This statement is so true that the could be infinitely extended, widened enough to obtain an that corresponds to it in an infinite significance, as long as it remains limited in its context; yet, without meaning anything from a clinical point of view in other contexts, like in the neurologist one, for instance.

Final considerations

From a perspective of observation of this kind, the Logic of Predicates can only fortify the dentist’s reasoning and, at the same time, strengthen the principle of the excluded third: the principle is strengthened through the compatibility of the additional assertions which grant the dentist a complete coherence in the diagnosis and in confirming the sentence : Poor Mary Poppins either has TMD, or she has not.«...and what if, with the advancement of research, new phenomena were discovered that would prove the neurologist right, instead of the dentist?»

|

Basically, given the compatibility of the assertions , coherently saying that Orofacial Pain is caused by a Temporomandibular Disorders could become incompatible if another series of assertions were shown to be coherent: this would make a different sentence compatible : could poor Mary Poppins suffer from Orofacial Pain from a neuromotor disorder (nOP) and not by a Temporomandibular Disorders?

In the current medical language logic, such assertions only remain assertions, because the convictions and opinions do not allow a consequent and quick change of the mindset.

Moreover, taking into account the risk that this change entails, in fact, we might consider a recent article on the epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders[36] in which the authors confirm that despite the methodological and population differences, pain in the temporomandibular region appears to be relatively common, occurring in about the 10% of the population; we may then objectively be led to hypothesize that our Mary Poppins can be included in the 10% of the patients mentioned in the epidemiological study, and contextually be classified as a patient suffering from Orofacial Pain from Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs).

In conclusion, it is evident that a classical logic of language, which has an extremely dichotomous approach (either it is white or it is black), cannot depict the many shades that occur in real clinical situations.

We need to find a more convenient and suitable language logic...«... can we then think of a Probabilistic Language Logic?»

(perhaps) |

- ↑ Stanley DE, Campos DG, «The logic of medical diagnosis», in Perspect Biol Med, 2013».

PMID:23974509

DOI:10.1353/pbm.2013.0019 - ↑ Croskerry P, «Adaptive expertise in medical decision making», in Med Teach, 2018».

PMID:30033794

DOI:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1484898 - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Townsend GC, Brook AH, «The face, the future, and dental practice: how research in craniofacial biology will influence patient care», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24646132

DOI:10.1111/adj.12157 - ↑ Sperber GH, Sperber SM, «The genesis of craniofacial biology as a health science discipline», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24495071

DOI:10.1111/adj.12131 - ↑ Brook AH, Brook O'Donnell M, Hone A, Hart E, Hughes TE, Smith RN, Townsend GC, «General and craniofacial development are complex adaptive processes influenced by diversity», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24617813

DOI:10.1111/adj.12158 - ↑ Williams SD, Hughes TE, Adler CJ, Brook AH, Townsend GC, «Epigenetics: a new frontier in dentistry», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24611746

DOI:10.1111/adj.12155 - ↑ Yong R, Ranjitkar S, Townsend GC, Brook AH, Smith RN, Evans AR, Hughes TE, Lekkas D, «Dental phenomics: advancing genotype to phenotype correlations in craniofacial research», in Aust Dent J, Australian Dental Association, 2014».

PMID:24611797

DOI:10.1111/adj.12156 - ↑ Thesleff I, «Current understanding of the process of tooth formation: transfer from the laboratory to the clinic», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12102 - ↑ Peterkova R, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Lesot H, «Three‐dimensional analysis of the early development of the dentition», in Aust Dent J, Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd on behalf of Australian Dental Association, 2014».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12130 - ↑ Lesot H, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Peterkova R, «Three‐dimensional analysis of molar development in the mouse from the cap to bell stage», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12132 - ↑ Hughes TE, Townsend GC, Pinkerton SK, Bockmann MR, Seow WK, Brook AH, Richards LC, Mihailidis S, Ranjitkar S, Lekkas D, «The teeth and faces of twins: providing insights into dentofacial development and oral health for practising oral health professionals», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12101 - ↑ Han J, Menicanin D, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, «Stem cells, tissue engineering and periodontal regeneration», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12100 - ↑ {{Cite book | autore = Brook AH | autore2 = Jernvall J | autore3 = Smith RN | autore4 = Hughes TE | autore5 = Townsend GC | titolo = The Dentition: The Outcomes of Morphogenesis Leading to Variations of Tooth Number, Size and Shape | url = https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/adj.12160 | volume = | opera = Aust Dent J | anno = 2014 | editore = | città = | ISBN = | PMID = | PMCID = | DOI = 10.1111/adj.12160 | oaf = | LCCN = | OCLC =

- ↑ Seow WK, «Developmental defects of enamel and dentine: challenges for basic science research and clinical management», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

PMID:24164394

DOI:10.1111/adj.12104 - ↑ Kieser JA, Farland MG, Jack H, Farella M, Wang Y, Rohrle O, «The role of oral soft tissues in swallowing function: what can tongue pressure tell us?», in Aust Dent J, 2013».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12103 - ↑ Slavkin HC, «Research on Craniofacial Genetics and Developmental Biology: Implications for the Future of Academic Dentistry», in J Dent Educ, 1983».

PMID:6573384 - ↑ Slavkin HC, «The Future of Research in Craniofacial Biology and What This Will Mean for Oral Health Professional Education and Clinical Practice», in Aust Dent J, 2014».

PMID:24433547

DOI:10.1111/adj.12105 - ↑

Littlewood SJ, Kandasamy S, Huang G, «Retention and relapse in clinical practice», in Aust Dent J, 2017».

DOI:10.1111/adj.12475 - ↑ Miamoto CB, Silva Marques L, Abreu LG, Paiva SM, «Impact of two early treatment protocols for anterior dental crossbite on children’s quality of life», in Dental Press J Orthod, 2018».

- ↑ Alachioti XS, Dimopoulou E, Vlasakidou A, Athanasiou AE, «Amelogenesis imperfecta and anterior open bite: Etiological, classification, clinical and management interrelationships», in J Orthod Sci, 2014».

DOI:10.4103/2278-0203.127547 - ↑ Mizrahi E, «A review of anterior open bite», in Br J Orthod, 1978».

PMID:284793

DOI:10.1179/bjo.5.1.21 - ↑ For the sake of simplicity of exposition and reading, we will deal in this chapter with the symbol of belonging, the symbol of consequence and the "such that" as if they were quantifiers and connectives of propositions in classical logic.

Strictly speaking, within classical logic they should not be treated as such, but even if we do, this does not absolutely change the meaning of the speech and no inconsistencies of any kind are created. - ↑ Pereira LM, Pinto AM, «Reductio ad Absurdum Argumentation in Normal Logic Programs», Arg NMR, 2007, Tempe, Arizona - Caparica, Portugal – in «Argumentation and Non-Monotonic Reasoning - An LPNMR Workshop».

- ↑ Castroflorio T, Talpone F, Deregibus A, Piancino MG, Bracco P, «Effects of a Functional Appliance on Masticatory Muscles of Young Adults Suffering From Muscle-Related Temporomandibular Disorder», in J Oral Rehabil, 2004».

PMID:15189308

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01274.x - ↑ Maeda N, Kodama N, Manda Y, Kawakami S, Oki K, Minagi S, «Characteristics of Grouped Discharge Waveforms Observed in Long-term Masseter Muscle Electromyographic Recording: A Preliminary Study», in Acta Med Okayama, Okayama University Medical School, 2019, Okayama, Japan».

PMID:31439959

DOI:10.18926/AMO/56938 - ↑ Rudy TE, «Psychophysiological Assessment in Chronic Orofacial Pain», in Anesth Prog, American Dental Society of Anesthesiology, 1990».

ISSN: 0003-3006/90

PMID:2085203 - PMCID:PMC2190318 - ↑ Woźniak K, Piątkowska D, Lipski M, Mehr K, «Surface electromyography in orthodontics - a literature review», in Med Sci Monit, 2013».

e-ISSN: 1643-3750

PMID:23722255 - PMCID:PMC3673808

DOI:10.12659/MSM.883927 - ↑ Liang X, Liu S, Qu X, Wang Z, Zheng J, Xie X, Ma G, Zhang Z, Ma X, «Evaluation of Trabecular Structure Changes in Osteoarthritis of the Temporomandibular Joint With Cone Beam Computed Tomography Imaging», in Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2017».

PMID:28732700

DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2017.05.514 - ↑ Solberg WK, Bibb CA, Nordström BB, Hansson TL, «Malocclusion Associated With Temporomandibular Joint Changes in Young Adults at Autopsy», in Am J Orthod, 1986».

PMID:3457531

DOI:10.1016/0002-9416(86)90055-2 - ↑ KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach / Ris

- ↑ Kobs G, Didziulyte A, Kirlys R, Stacevicius M, «Reliability of ARCUSdigma (KaVo) in Diagnosing Temporomandibular Joint Pathology», in Stomatologija, 2007».

PMID:17637527 - ↑ Piancino MG, Roberi L, Frongia G, Reverdito M, Slavicek R, Bracco P, «Computerized axiography in TMD patients before and after therapy with 'function generating bites'», in J Oral Rehabil, 2008».

PMID:18197841

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01815.x - ↑ López-Cedrún J, Santana-Mora U, Pombo M, Pérez Del Palomar A, Alonso De la Peña V, Mora MJ, Santana U, «Jaw Biodynamic Data for 24 Patients With Chronic Unilateral Temporomandibular Disorder», in Sci Data, 2017».

PMID:29112190 - PMCID:PMC5674825

DOI:10.1038/sdata.2017.168

This is an Open Access resource! - ↑ Myotronics Inc., Kent, WA, US

- ↑ Oliveira Mazzetto M, Almeida Rodrigues C, Valencise Magri L, Oliveira Melchior M, Paiva G, «Severity of TMD Related to Age, Sex and Electromyographic Analysis», in Braz Dent J, 2014».

DOI:10.1590/0103-6440201302310 - ↑ LeResche L, «Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors», in Crit Rev Oral Biol Med, 1997».

PMID:9260045

DOI:10.1177/10454411970080030401

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system